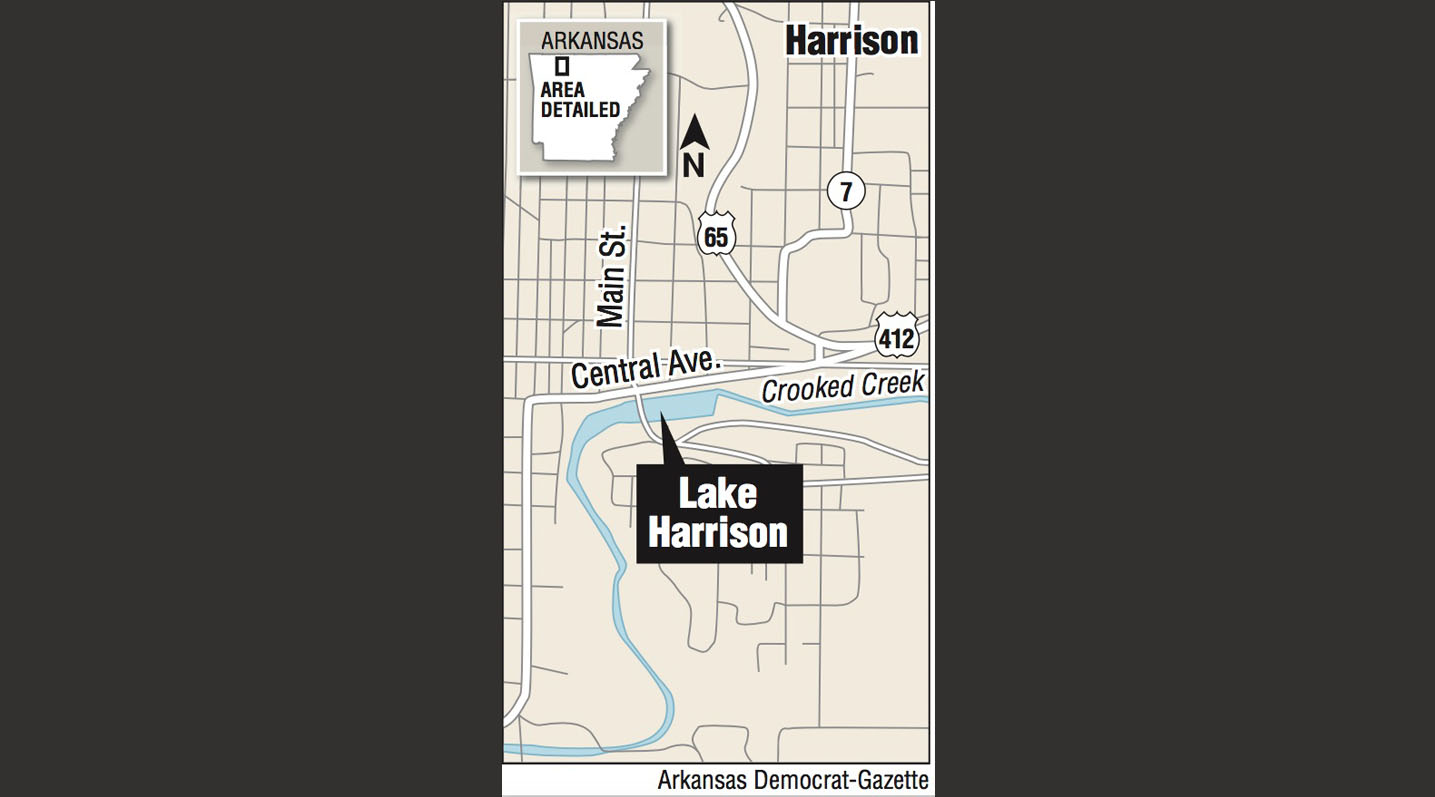

A plan to remove a lake alongside downtown Harrison and restore Crooked Creek as a free-flowing stream has run aground -- at least for now.

After the Arkansas Department of Transportation offered to pay up to $2.86 million toward the project, and the Harrison City Council passed a resolution approving it, they learned that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers did the initial work, so that agency will get the final say over what happens.

"They're in charge of the project," said Wade Phillips, Harrison's chief operating officer and city engineer.

The initial idea involved removing a 10-foot-tall weir, or low-head dam, in Crooked Creek that created Lake Harrison in the 1990s.

Creating the lake seemed like a good idea at the time. But sediment flows in from upstream and piles up against the weir, filling the bottom layer of the stream bed.

Then came the geese.

And with them, "the unsightly, and unsanitary, geese poop," as Mayor Jerry Jackson wrote in a column earlier this year for the Harrison Daily Times.

Canadian geese prefer the still water of a lake, wrote Jackson, instead of a flowing stream that could provide recreation for kayakers and swimmers.

Phillips said the Corps wants to conduct a study, and it'll be several months before that study begins.

"It's going to slow things down," said Phillips, "but it's better than saying the project is dead in the water."

Phillips said the city had reached an agreement with the Arkansas Department of Transportation to partner on the project.

"They were essentially going to fund the project by purchasing stream restoration credits from the city once the project was done," said Phillips. The mitigation credits are available under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act.

But the Corps was concerned that planting grasses and woody vegetation along the stream bank could increase flooding upstream, which was a problem before the weir was built, said Phillips.

Since Crooked Creek flows in a northeasterly direction, upstream is actually south of Harrison.

"If the civil-works side of the Corps of Engineers weren't going to let us plant along that stream bank, it doesn't really do much good to restore it because you can't get the restoration credits at that point," said Phillips.

Basically, "the Corps didn't really want to trust our numbers," he said. So they're going to do their own study.

The original weir construction falls under Section 1135 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1986, which allows the Corps "to make modifications to operations or structures of civil works projects previously constructed by USACE, for the purpose of improving the quality of the environment."

"It lets them go back and redo stuff that they did in the past that turned out not to be the most environmentally sound choice," said Phillips.

When the state transportation department sent out a prospectus for the work last year, the Corps raised a red flag, said Phillips.

The regulatory side of the Corps of Engineers, which deals with stream restoration, was all for the project, said Phillips.

"Unfortunately, when the works side of the Corps of Engineers -- the ones that actually build the projects -- they flagged it as problematic because of the way it got funded originally back in the mid- to late 1990s," said Phillips. "It was done as a small flood-control project that was funded through a congressional appropriation."

That work included a lot of clearing and grubbing. That means removing any trees, breaches, roots and snags larger than 3 inches in diameter.

"The weir itself was justified and funded as a way to make up for loss of fish habitat caused by clearing and grubbing," said Phillips. "So the weir had no flood-control function whatsoever. Basically, the Corps study back in the 1990s said clearing and grubbing would reduce the potential for flooding upstream of Lake Harrison.

"When we do a stream restoration, one of the most important parts is to establish a riparian zone along that stream, which is going to include appropriate vegetation along that stream bank, and it's going to be a mix of grasses and trees and woody vegetation," said Phillips. "One side of the Corps of Engineers came back and said 'You can't do that.' And so that's where we got stuck because it doesn't do us any good to tear out and try to restore what looks like a stream without establishing a good riparian zone that prevents erosion."

Crooked Creek remained relatively uncontentious until May 7, 1961.

On that day, in the early morning darkness, "while a tornado-whipped thunderstorm lashed the heavens, a ten-foot wall of water from rain-swollen Crooked Creek roared suddenly through the heart of town killing three persons, demolishing fifteen homes and wiping out or severely crippling 80 per cent of the local business establishments," according to a May 10, 1961, article by Cabell Phillips in the New York Times.

Four people actually died in the 1961 flood, said Ken Reeves, a former chairman of the Arkansas Game & Fish Commission, who was a 13-year-old Harrison boy in 1961.

"After the massive flood of 1961, the city applied for and was approved for Urban Renewal funds to build the current levee and widen the creek bed by scraping the drainage down to bedrock," Jackson wrote in his newspaper column. "The hoped for result was that a wider creek would not pour its waters into downtown when the next big flood came. Thankfully, the levee worked; however, every time the creek had a big rise, gravel and silt began to fill the massive cavity that had been made. Soon, willows and other natives began growing in the creek bed. In just a few years the area became an ugly wound in the middle of town."

In the early 1990s, "a group of Harrison leaders proposed turning the swampy willow jungle into a small lake with walkways and play areas all around it," wrote Jackson.

It was beautiful, but then the annual floods came and the lake began to fill up with silt, wrote Jackson.

"It became stagnant," he wrote. "Each summer, it actually had a bad smell."

About every other year, the city would have to drain the lake and pay to have the silt dredged and hauled away, at an annualized cost of about $100,000.

"Then the Canadian geese came," wrote Jackson. "Lots of geese. We tried several humane methods to rid the lake of the geese, but the population -- and the poop -- continued to grow. Now, we send city crews almost daily to the lake to clean the unsightly, and unsanitary, geese poop."

The Arkansas Department of Transportation plans to start work soon to replace the Crooked Creek bridge on U.S. 65B over Lake Harrison. The bridge will be closed from Tuesday until the summer of 2026.

The suggested detour uses U.S. 65 and Arkansas 7.