Sarasin was a Quapaw leader who became a legend among white Arkansas settlers for rescuing white children captured by other American Indians. Many versions of this story exist in Arkansas folklore. But less well remembered were Sarasin's struggles to help his people, the Quapaw, who lived in three villages along the Arkansas River below what is now Pine Bluff, during the era of Indian Removal.

The basic legend about Sarasin concerns the late 18th-century capture of two children by a Chickasaw raiding party. Sarasin went to the children's mother and vowed to rescue them. He rowed down the river until he came upon the Chickasaw camp near Arkansas Post. In the middle of the night, he went into the camp, lifted up his tomahawk, and gave the Quapaw war cry. Fearing that Quapaw warriors were upon them, the Chickasaws fled. Sarasin returned the children unharmed to their mother.

Sarasin was given a presidential medal by the first territorial governor, James Miller, symbolizing American recognition of his leadership. Such friendship, however, did not extend to the entire Quapaw nation. Settlers and territorial officials, coveting valuable Quapaw land on the Arkansas River, began to call for the removal of the Quapaw in the 1820s. In the tragic ordeal that followed, Sarasin made his greatest contribution to his people.

In the treaty of 1824, the Quapaw ceded their land, which extended from the mouth of the Arkansas River to Little Rock and southwest to the Ouachita River. In return, they received land among the Caddo tribes on the Red River in northeastern Louisiana and a $1,000 annual annuity, which the U.S. government took years to pay. The treaty also reserved land along the Arkansas River for 11 mixed-blood Quapaw — including Sarasin, who received 80 acres.

The Quapaw moved to Caddo country in early 1826. There, floods destroyed crops; starvation killed 60 people, including Sarasin's wife and other members of his family; and bureaucratic confusion undermined the confidence the Quapaw had in government agents. After six months there, Sarasin broke with Heckaton, the principal chief, and led one-fourth of the nation back to the land reserved for him on the Arkansas River.

After their return in 1827, Sarasin and other leaders of the Arkansas band met in council and explained their actions in a letter to President John Quincy Adams. The council expressed the desire to remain in Arkansas and asked the president to protect them from further threat of removal. They also requested that the young men be taught to plow and the women to spin and weave.

The federal government responded by awarding one-fourth of the Quapaw annuity to the Arkansas band but, in hopes of persuading Sarasin and his band to leave Arkansas again, prohibited them from using the annuity money to buy land. Sarasin thus persuaded George Izard, the governor of Arkansas Territory and government-appointed agent for the Quapaw, to use the annuity to buy agricultural implements for the Quapaw. He arranged with Izard to send 10 Quapaw boys to school with a local teacher named Wigton King. Sarasin recognized that the Quapaw had to overcome their dependency on whites who provided them with manufactured goods and repaired their implements.

By 1830, principal chief Heckaton led the rest of the Quapaw back to Arkansas from the Caddo country. Heckaton abandoned the Red River settlements and led the remnant of the nation back to the Arkansas River. Sarasin and Heckaton pleaded with federal and territorial officials to allow the Quapaw to remain in Arkansas. Sarasin was promised only that he could remain in the territory.

In 1832, the Quapaw finally received annuity payments that had been denied them for years. It was too little and too late. Unable to buy land, many Quapaw were pushed off their farms by white settlers, and some found refuge only in the swamps. With their situation becoming more tenuous, the Quapaws signed a treaty in 1833 by which they agreed to move to the northeastern corner of Indian Territory.

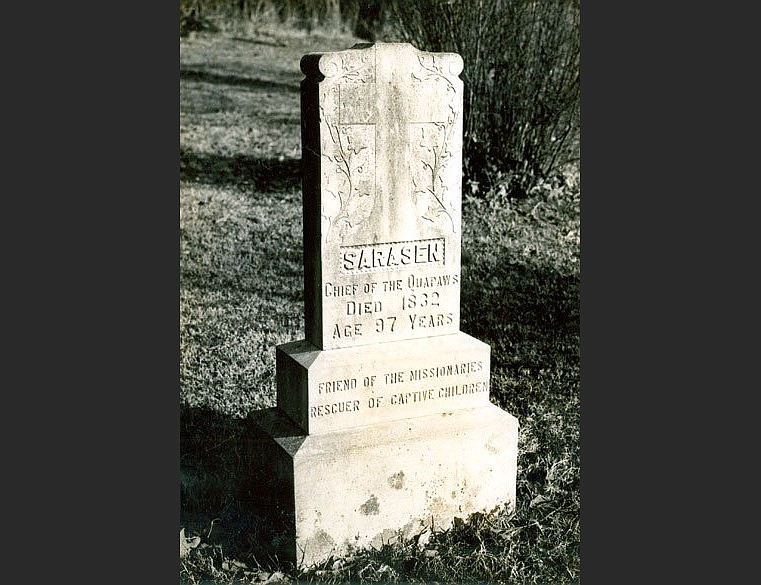

Sarasin did not go to the new reservation. Instead, he led 300 Quapaw back to the Red River in Louisiana. He soon returned to Arkansas and lived in Jefferson County until his death. While his gravestone records that he died in 1832, it is clear that he lived beyond that year. His body was later re-buried in the cemetery of St. Joseph's Church in Pine Bluff. His gravestone was inscribed: "Friend of the Missionaries. Rescuer of captive children."

— Joseph Patrick Key

This story is adapted by Guy Lancaster from the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas, a project of the Central Arkansas Library System. Visit the site at encyclopediaofarkansas.net.