To the surprise of government transparency advocates and even at least one senator who voted for it, a bill that sailed through the Arkansas Legislature this year contains a provision that will expand the circumstances in which school boards can discuss matters in private.

Sen. Clarke Tucker, D-Little Rock, who was among 31 of the state's 35 senators who voted in favor of Senate Bill 543, said the legislation "creates a significant gap" in the state's Freedom of Information Act that he doesn't support.

Had he known about the provision, he said, "I absolutely would have voted no on the bill."

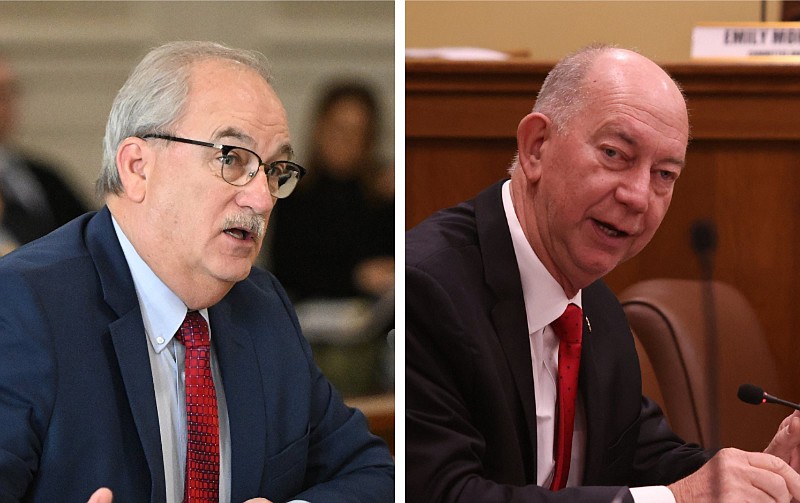

The legislation, which was sponsored by Sen. Kim Hammer, R-Benton, and Rep. Bruce Cozart, R-Hot Springs, was signed by Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders on April 13 and became Act 883.

It is titled "An act to amend Arkansas law concerning school district boards of directors; amending a portion of law resulting from initiated Act 1 of 1990; and for other purposes."

The law goes into effect May 1 of next year and largely addresses school board accountability, with sections increasing the role of the state Ethics Commission in the oversight of school boards and requiring board members to sign an oath regarding special interests.

"The meat of the bill and the overall intent of the bill was to bring a higher level of accountability to school boards by putting it in front of the Ethics Commission," Hammer said in an interview Thursday.

Section 3 of the law, however, will broaden the situations in which school board members can meet in private discussions, known as executive sessions.

It will allow such sessions for pre-litigation discussions, for litigation updates, to discuss and consider settlement offers, to discuss and consider contract disputes with the district superintendent and to discuss real property. The board may also invite the superintendent and attorney for the school district to be present during the executive session.

Currently under the state Freedom of Information Act, with a few exceptions, governing bodies of public entities can go into executive session only when considering the "employment, appointment, promotion, demotion, disciplining, or resignation of any public officer or employee."

Besides members of the governing body, only the person holding the top administrative job at the agency, the employee being discussed and the employee's direct supervisor are allowed to attend such sessions.

Supporters of the Freedom of Information Act, a 1967 law intended to increase government transparency, said they were not aware of Section 3 until several months after SB543 was signed.

The bill passed 31-2 in the Senate and 94-0 in the 100-member House.

"I know it got by me, and I think got by a lot of other folks," said Tucker, who also serves on the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act Review Working Group created by state Attorney General Tim Griffin in mid-June. The group is intended to review and suggest modernizations to the law.

Robert Steinbuch, a University of Arkansas at Little Rock professor, and Little Rock attorney John Tull III said they also failed to spot the change.

Both are members of the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act Task Force, which was created by state law in 2017 to review proposed changes to the transparency law and make recommendations to the Legislature.

"We dropped the ball," Steinbuch said.

Tull, who also serves alongside Tucker on Griffin's working group, said "numerous people in different organizations" watch for proposed alterations to the Freedom of Information Act. The task force voted in late March to oppose bills that would have increased the types of records that are exempt from public inspection and allowed members of governing bodies to meet privately in small groups to discuss public business.

Tucker said SB543, which was filed the day after the task force decided to oppose those other two pieces of legislation, came during a point in the legislative session in which lawmakers were "voting on upward of a hundred bills a day."

"There's just too many bills for you to be able to read every word of every bill," he said.

[DOCUMENT: Read the Senate bill that became Act 883 » arkansasonline.com/723act883/]

Hammer said the ability to have a lawyer in executive sessions allows school boards to go through a "more thorough process for the board to make an educated decision." It provides space for board members to have a "frank discussion" without the need to go back and forth between executive and public sessions when talking with their attorney, according to the senator. He said that decisions made without adequate discussion can harm both the school district and taxpayers.

"Ultimately, any decision is going to have to be a public decision that will have been well vetted by giving the attorney and the district that latitude to have that kind of behind-doors conversation," he said.

Critics of Section 3 said they believed the additional conditions in which a school board could enter executive session were too open-ended.

"Those topics are written so broadly that if a school board wants to expand the definition, it easily could," Tull said. "It would be very difficult to stop it because there's no definition of what is pre-litigation."

He pointed to the Huntsville School District, which was accused in a 2021 lawsuit of failing to notify the media about meetings of the School Board to discuss a sexual harassment case.

"That could have easily been swept under the rug even more so by claiming that that was all pre-litigation," he said.

Donn Mixon, an attorney who serves on retainer as legal counsel to roughly 45 districts in Arkansas, said that he has "mixed feelings" about the law.

The attorney said he prefers to remain at a distance from the school boards and worries that being invited into executive sessions will make that more difficult. He doesn't want to be in an executive session where he could be lobbied by the board.

"I want to be able to give what I believe to be an accurate view of what a court would do," he said.

James H. Jones III, superintendent of the Cotter School District in north Arkansas, said he could see the need for districts to discuss the purchase or sale of property privately, so that those on the other end of such transactions can't take advantage of otherwise public discussions.

Despite his overall disapproval of Section 3, Tucker agreed that allowing closed-door discussions about real estate makes sense.

"If a school district hypothetically is going to sell a piece of real property and the school board needs to have a conversation about what they're going to take, then I can understand that conversation being private," he said. "Because then anyone would know what their bottom line is."

Mixon expressed the worry that the law could lead to districts planning out the purchase of property without any accountability by the public until the decision to move forward has all but been made.

For his part, Jones said he doesn't anticipate his district often needing to take advantage of the changes to the open-records law.

"Most of our things are pretty cut and dry," he said. But he added that he was glad to know the exemptions will be there.

"It's just a new tool in the toolbox that we can use if needed," Jones said.

CALL FOR GREATER TRANSPARENCY

Tull and other Freedom of Information Act watchdogs said they flatly oppose laws that make private previously public information regarding schools.

"I always think discussions should be open and in particular in public schools, so that the parents can understand what issues a particular school [is] having and how they're addressing them," Tull said.

Tucker said he believed Arkansas' Freedom of Information Act to be one of the strongest open-records laws in the nation, "and that's the way it ought to stay." He added that public access to information is essential to governing in the state, and that any exceptions made to the law need to be handled very cautiously.

Steinbuch said, "I'm not antithetical to the notion of the government but what I do know is an unchecked government inherently becomes unhealthy to our freedoms."

The professor said he believes lawmakers should notify the Freedom of Information Act Task Force when filing laws that will affect the open-records law.

"It should be reciprocal," he said.

Steinbuch proposed that lawmakers add into the Freedom of Information Act a requirement that proposed amendments to the open-meetings law be stated clearly in the title of such legislation.

However, Hammer, who said he has a voting record of protecting and favoring the Freedom of Information Act, denied that his law will harm the public's access to important information. The senator said he believed at the time that the task force would have come out in opposition to the law if they saw an issue with it.

"Quite honestly I felt if it was a problem that they would have detected it, because that's their job, to look at legislation to see if there's anything," he said.

Going forward, though, the senator said that, if this has caused members of the task force concern, he will work toward putting in front of them any proposed changes to the law on open meetings and records.