When the Supreme Court ruled Thursday that Alabama's congressional map had diluted the power of Black voters, it was a long-sought victory for voting-rights activists, who had grown increasingly alarmed at the court's previous decisions that have hollowed out the Voting Rights Act.

The decision is also seen as likely to reverberate across the South and could force multiple states with pending Voting Rights Act challenges to redraw their maps.

In Alabama, a state with a tortured history of Jim Crow laws and voter suppression, the court's ruling against the legislatively drawn maps was a significant victory for Black voters. The court affirmed a lower court's decision to create a second congressional district "in which Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it."

And the ruling offered many Alabama voters a much-needed assurance that the Voting Rights Act's other protections held strong, especially in a state that was the origin of one of the most damaging decisions to the landmark act.

Nearly a decade ago, a case out of Shelby County, Ala., led to one of the most sweeping decisions against the Voting Rights Act, effectively neutering the law that had required federal approval before states with a history of discrimination could change their voting laws.

That combined history of discrimination and legal defeats left many Black leaders in Alabama uneasy about the case before the Supreme Court, concerned that it could erode civil rights protections once again, instead of bolstering them.

Evan Milligan, a plaintiff in the Supreme Court case and executive director of Alabama Forward, a civil-rights organization, said he questioned whether this case was the right one to pursue. "But ultimately it felt like the right move to be involved," he said, "and this outcome affirms that decision."

So while it took a battle all the way to the Supreme Court to get a second majority-Black district out of a seven-seat congressional delegation in a state where 25% of the voting-age population is Black, Black leaders in Alabama hailed the victory. They said it was a reminder to continue the fight for voting rights and civil rights -- especially in the South.

"It's a new day, and it's a new day especially for the Deep South," said Rep. Terri A. Sewell, the lone Democrat in Alabama's congressional delegation. Sewell, who is Black, has pushed for change in Alabama's maps, even if it means weakening her own district. "I'm excited about what it means for African American voters in my state. But I'm also excited about what it means for minority voters at large in this nation. They deserve fair representation and representation does matter," she said.

Hank Sanders, a former Alabama state lawmaker who has long been politically active in the state, knew there would be a decision since the court heard arguments in the case last fall. He was not anticipating being happy with the outcome, given that previous rulings of the conservative-leaning court had essentially gutted some of its most important provisions.

"I was afraid they were going to go ahead and wipe out Section 2," he said, referring to the part of the Voting Rights Act at stake in the Alabama case.

He was at his law office Thursday in Selma, scene of one of the most pivotal moments in the Civil Rights Movement, when news of the 5-4 ruling in favor of Alabama's Black voters was announced.

"It was a surprise that was good for my day," he said.

ARKANSAS CASE

How the decision will affect similar lawsuits against political maps drawn in other states is unclear, although voting rights groups say the ruling provides firm guidance for lower courts to follow.

The court majority found that Alabama concentrated Black voters in one district, while spreading them out among the others to make it much more difficult to elect more than one candidate of their choice. Alabama's Black population is large enough and geographically compact enough to create a second district, the judges found. Just one of its seven congressional districts is majority Black, in a state where more than one in four residents is Black.

The ruling could result in multiple Southern states having their maps struck down through pending Voting Rights Act challenges.

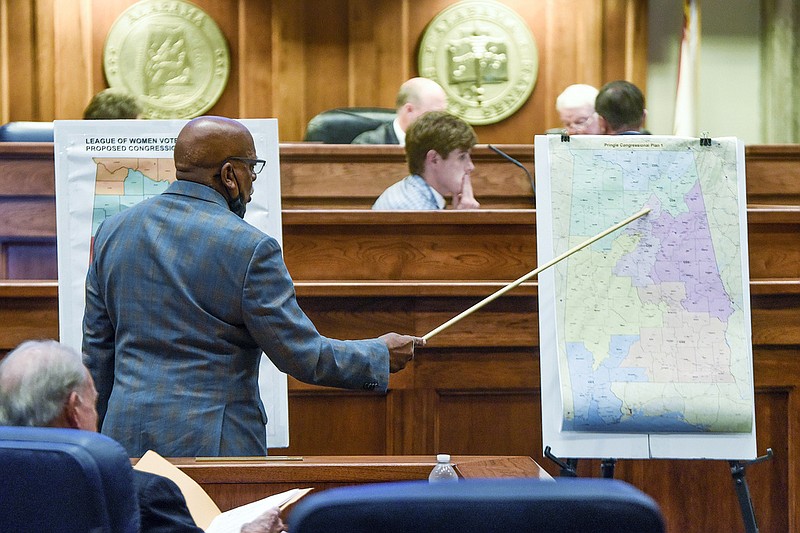

A case with similar overtones in Arkansas was recently tossed out by a three-judge Court of Appeals panel, which upheld the Arkansas congressional map resulting from a legislative decision to move 22,000 predominately Black voters out of Arkansas' 2nd Congressional District and replace them with 22,000 predominately white voters by moving Cleburne County from the 1st Congressional District to the 2nd. In dismissing the case, the panel ruled that the plaintiffs, represented by Little Rock attorney Richard Mays, had failed to establish racial discrimination as the motive for the decision.

"The Supreme Court approved a decision based upon facts very similar to the ones in our case in which the [Alabama] three-judge-panel pretty much adopted, I thought, our position," Mays said. "So I think it helps. I don't think it's a guarantee that we would prevail, but I think it makes it a better argument."

Mays filed the lawsuit in March 2022 on behalf of six Pulaski County voters, including two state legislators, who accused the state of diluting the Black vote in the 2nd District through a gerrymandering method known as "cracking," which is used to disperse voters of similar interests among populations with which they hold little in common. The plaintiffs -- Jackie Williams Simpson, Wanda King, Charles Bolden, Anika Whitfield, state Rep. Denise Ennett, D-Little Rock, and state Sen. Linda Chesterfield, D-Little Rock -- accused the state of violating the U.S. Constitution, the state constitution and the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 by diluting Black voting power and influence through the newly drawn map. The lawsuit named then-Gov. Asa Hutchinson, Secretary of State John Thurston and the state of Arkansas as defendants.

A panel of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals -- Judge David Stras, Chief U.S. District Judge D. Price Marshall Jr. and U.S. District Judge James M. Moody Jr. -- dismissed all defendants but Thurston from the lawsuit and dismissed claims the map violated the U.S. Constitution.

Mays said that while the Alabama case doesn't directly parallel the Arkansas lawsuit, the Supreme Court ruling did address one important question he said the panel got wrong in Arkansas.

"They said we failed to create a plausible inference that the legislature as a whole was imbued with racial motives," Mays said. "I think we did show there was a racial motivation on the part of the Republican leaders, but to show that everyone who voted for the map had a racial motivation would be impossible. I think the court is wrong there and I do plan to appeal it."

Thursday's Supreme Court ruling, Mays said, offers a window of hope that an appeal before the high court might succeed because of Chief Justice John Roberts' statement in the majority opinion that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, "turns on the presence of discriminatory effects, not discriminatory intent," which Mays said, "is exactly what we've been saying all along."

LOUISIANA, GEORGIA, TEXAS

In Louisiana, where Black voters make up one-third of the population, a case before the Supreme Court had been put on hold pending the Alabama decision. Now a second majority-Black district could be drawn.

"We know that in compliance with the principles of the Voting Rights Act, Louisiana can and should have a congressional map where two of our six districts are majority Black," Gov. John Bel Edwards of Louisiana, a Democrat, said Thursday. "Today's decision reaffirms that."

Rep. Troy Carter, a Black Democrat representing Louisiana's lone district that is majority Black, said the Legislature should immediately convene to draw a second majority-minority district.

"This Supreme Court ruling is a win not just for Alabamians but for Louisianans as well," Carter said in an emailed statement. "Rarely do we get a second chance to get things right -- now Louisiana can."

The Supreme Court decision is also expected to send legislators in Georgia back to the drawing board for their congressional maps. On Thursday, a federal judge in a pending Georgia case asked both parties to provide supplemental materials in light of the new ruling.

Bishop Reginald Jackson, a plaintiff in one of the lawsuits challenging Georgia's congressional map, said he was ecstatic when he heard the news about the ruling and hopes it will boost their case.

He said he became involved in the lawsuit amid concerns that the state's Black population had increased while the number of Black congressional representatives had decreased with the last round of redistricting.

"So how could you have less Black representation when you have more Blacks moving into the state than before?" said Jackson, who presides over 534 African Methodist Episcopal churches in Georgia with over 90,000 parishioners.

In Texas, where Republicans drew an aggressive gerrymander that could lock in power for a decade, nine cases in the federal court system could be affected by Thursday's decision, according to a tracker kept by the Brennan Center for Justice, a think tank.

FUTURE IMPLICATIONS

Across the South, the decision will most likely add three majority-Black districts in reliably red states, changes that will upend what will be a pitched battle for control of the House of Representatives next year.

And in an era of racially polarized voting, where 87% of Black voters nationally voted for Joe Biden, according to exit polls, adding three majority-Black districts would increase Democrats' odds of retaking control of the chamber.

In Alabama, voting-rights advocates and local leaders said the ruling could reverse a sense of apathy that has pervaded the state, across the political spectrum, as many residents had come to feel that elections were foregone conclusions and their ballots made little difference.

"It's a great day in Alabama," said Bobby Singleton, a Democrat and Black from Greensboro who serves as the state Senate minority leader. But Singleton also said: "Racism is still alive and well in the state of Alabama, and the Supreme Court was able to see it."

Robyn Hyden, the executive director of Alabama Arise, which is focused on policies supporting poor residents, said she had been uncertain of what to expect from the court, but she felt there was a solid case to make. "Their reasons and their arguments were sound to me," she said.

She argued that the geography of the 7th Congressional District, represented by Sewell and reaching across a broad portion of the state, illustrated what made the map so problematic. "The idea that someone who lives in North Birmingham has the same political interests as someone who lives all the way down in Clark County, which is near the Gulf Coast of the state, is pretty ridiculous," she said. "It's four hours away."

"There are people in that district who are in the Black Belt, which is the most impoverished area of our state," she added. "There's people in that district who live in the largest cities in our state. It was really hard to think about how gerrymandered Birmingham and Montgomery have been, and how it has held back our regions from having political representation."

Information for this article was contributed by Nick Corasaniti and Rick Rojas of The New York Times; Gary Fields, Ayanna Alexander, Christina A. Cassidy, Sara Cline, Acacia Coronado, David A. Lieb and Kevin McGill of The Associated Press; and Dale Ellis of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.