Maybe history just likes repeating itself, did you ever think of that? Or maybe there's a scratch on the historic record. It repeats itself a lot, and not just in cascades of doom. Trifling bits of history replay again and again as though stuck in a loop.

Weather, for instance, excites abundant redundance.

For instance, we all know or ought to know that unpleasant weather is easier to tolerate when you just don't think about it. Focusing on humidity makes it stickier. Telling your co-workers over and over how much it bothers you doesn't help them feel better, either.

This also was true 100 years ago, as seen in a comic published in the Arkansas Gazette on June 13, 1923.

Syndicated by the long defunct New-York Tribune, Clare Briggs' funny shows a woebegone fellow hand-fanning himself as he wanders through an office and complains about heat and humidity. In the final cell, a furious colleague threatens to bludgeon him with a chair because he's making the place hotter.

Today, offices have air conditioning, but in 1923, offices had electric fans, large or small. They made a racket while they blew documents off desks. Fans rattled away in homes, stores, churches; and people were thrilled, they would sit through a sermon to be in front of one. At least First Presbyterian Church at Eighth and Scott streets in Little Rock appears to have thought so. It touted electric fans in notices announcing the pastor's Sunday lecture topics.

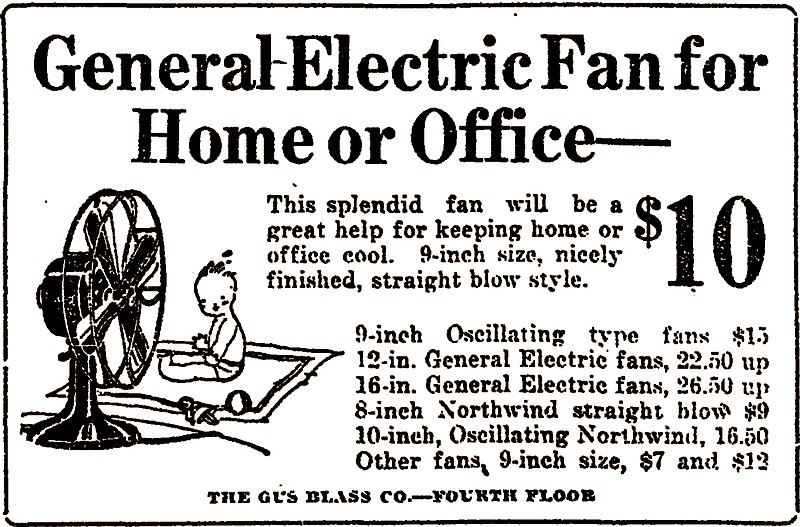

Fans were readily available in Arkansas stores, and, judging from the drawings in advertisements, potentially lethal. In these ads, no-see-um blades whirr behind spindly, bare-bones safety cages.

When I was a child in the '50s, kids liked to lean in behind a fan and sing, to hear our voices grumble out the other side, distorted. Heaven help any child of 1923 who tried that trick with one of the Robbins & Myers fans sold by W.P. Galloway Co. on Center Street or the General Electric fans sold on the fourth floor of the Gus Blass department store.

I mean, look at the drawings. Holy moly.

[Gallery not loading? Click here to see photos » arkansasonline.com/619fan/]

THE BAD HABIT

In other news of enduring consequence, letter writing was becoming a bad habit in 1923, according to essayist Frederic J. Haskin. The Gazette published a lot of his work, styling him as the Arkansas Gazette Information Bureau; but he was a big-time syndicated writer with a staff of helpers based in Washington.

His essay in the June 12, 1923, Gazette made me laugh out loud.

"It has been said that a wise man never writes a letter, and never destroys one," Haskin begins. "Another authority has it that one should never answer a letter until it is at least 30 days old, and then it will be found that it does not need answering.

"It has also been said that letter writing is a lost art — that it went into a decline along toward the latter part of the Nineteenth century when the world entered upon the modern age of hurry and men no longer had or took time for the leisurely observation and contemplation that are essential to the carrying on of a worthwhile correspondence."

But, he wrote, people who read newspapers had seen abundant evidence that letter writing was a bad habit for some people:

"It has come to pass that the public is never given the facts of a murder, a divorce, an elopement, a business or official scandal without being served with an unsavory mess of correspondence."

News hounds had become letter hounds. City editors who once sent their minions forth to gather facts and a few photos were now telling them to "dig up the letters in the case." Poor was the scandal without any kind of epistolary climax.

"Publishing the letters may be bad practice," he writes, "but the newspapers are not to be blamed primarily -- the letters could not be published if they had never been written."

Haskin explained that whenever an elderly gentleman "amatively diverted himself with some young siren of half his years," the truth of the saying about there being no fool like an old fool was almost invariably demonstrated. Men of shrewd judgment who barely bothered to scrawl the occasional picture postcard immediately succumbed to violent literary urges.

"And the kind of letters he writes! Passion? Romeo was a cold-blooded, unemotional fish in comparison! Sentiment? His very soul is so syrupy he drools sugar. ... And the rash statements he will make and the things he will commit himself to!" Haskin writes.

"In business he may be so conservative that he would not commit himself in writing to a declaration that Tuesday almost invariably follows Monday and precedes Wednesday until he first consults at least two lawyers. But in love he will dash off sentences that when read to a jury will convict him of obligating himself to everything from mayhem to matrimony."

Women are just as careless, Haskin notes, "and the only reason more men's letters get into print is because men are less prone to preserve such correspondence and are generally on the receiving end of the lawsuits that are instituted."

In other words, women save love letters, but men toss them in the trash, to be pilfered by snoops.

Women keep juicier diaries than men do, Haskin adds. They want to register chronologically every emotion of an affair of the heart. "This appears to be an especial weakness of romantic females who sooner or later discover that they love a man so ardently that they just naturally have to shoot him as proof of their affection."

Political men write ill-advised letters, Haskin says, referring vaguely to some scandal in which two famous men of opposite political parties were driven from public office because someone got hold of "a batch of letters that could not be explained once they had been published to the world. One is now dead and the other is a soured, embittered individual who is no longer good company for himself."

(Whatever was the case, these details don't seem to match up with the Navy's 1919 Newport sex scandal, Teapot Dome, the 1920 suicide of former Harvard student Cyril Wilcox, or the censure of Rep. Thomas L. Blanton of Texas for adding a letter containing cuss words to the Congressional Record.)

Haskin concludes, "And the moral of all this is, don't write a letter of any kind that you would not be perfectly willing to have the whole world read."

Change "letter" to "email," "tweet" or "text" and he might have filed his essay this morning.

PIE

I will leave you with one more repeating trifle, this from the June 11, 1923, Gazette. See whether you recognize recent viral events in the scenario here.

Mrs. Mary Warner, owner of a bakery in Chicago, had just arranged 50 of her best pies, chiefly strawberry. She was looking them over with pride when her shop door opened and in came a tall and ugly man with his hands in his coat pockets.

"You'd like a pie, of course?" she said, coming forward to meet him.

"I want what's in the cash box and I want it d—d quick," he responded, as he drew a pistol from each pocket.

Mrs. Warner thought and acted. Splash went a big strawberry pie over the countenance of the thug. She then rained pies upon him until he was thick with red goo. He dropped the pistols and ran out.

My, my, look at that "d—d." That was one of the words that got Blanton ejected from Congress, rather mild by today's standards. Let's hope my editors don't censure me for repeating it here.

Email: cstorey@adgnewsroom.com