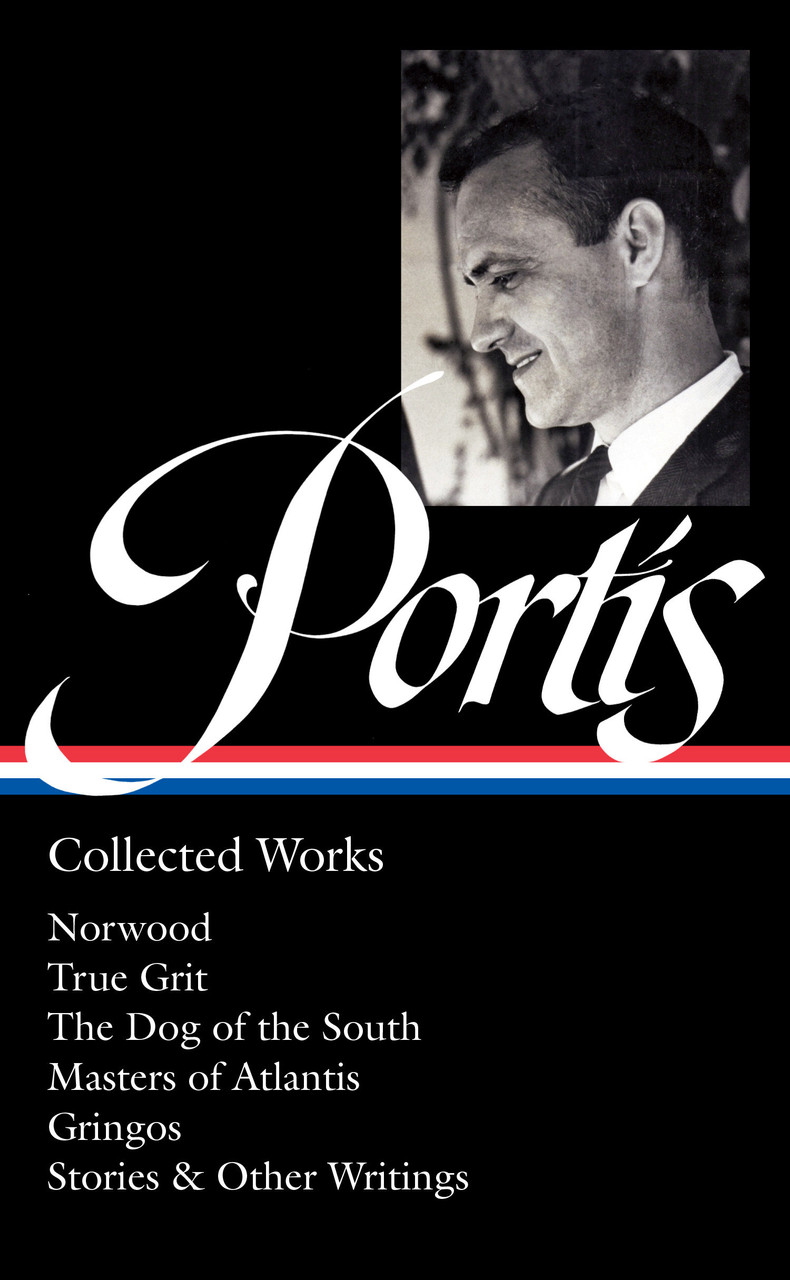

On April 4, the Library of America will publish “Charles Portis: Collected Works”— composed of contains all five of the Arkansas writer’s published novels — “Norwood,” “True Grit,” “The Dog of the South,” Masters of Atlantis” and “Gringos ” — along with a healthy selection of his stories and journalism.

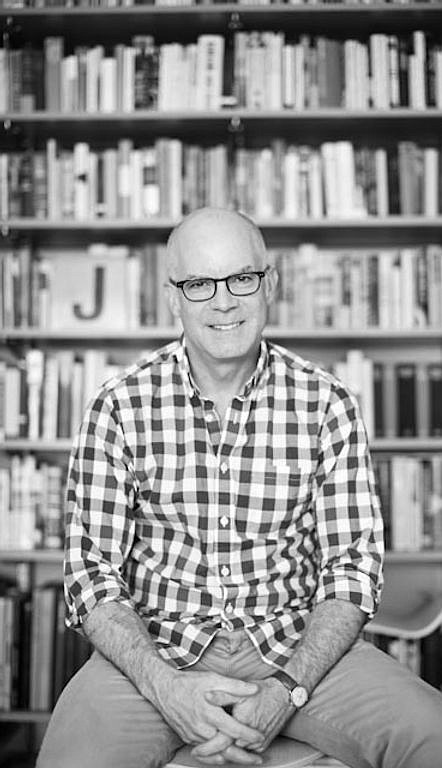

Little Rock’s Jay Jennings is the editor of that volume. He’s been a writer and editor for four decades, working on staff for Sports Illustrated, Time Out New York, and Oxford American and freelancing for the New York Times Book Review, Travel & Leisure, Garden & Gun, and the Lowbrow Reader, among many other magazines. His 2010 book about football, Central High School and Little Rock history, “Carry the Rock: Race, Football and the Soul of an American City” was recently reissued by the University of Arkansas Press in a revised edition, including a new preface by the author.

He lives in Little Rock with his family and his website is jayjennings.net.

We talked to him about his latest project.

Q. How did you come to know Charles Portis and how did you come to know his work?

A. In 1984, while I was teaching high school English in Dallas (a job I didn’t like and wasn’t very good at), I read a New York Times story about how “The Dog of the South” was so beloved by some New York bookstore employees that, five years after its publication, they bought all remaining copies and devoted a window on Madison Avenue to it. I knew Portis’s name from “True Grit” and knew he lived in Little Rock but had never read anything by him. I found a used copy of “Dog” in a Dallas bookstore, read it, and was hooked.

When I left that teaching job in 1985 and moved back in with parents in Little Rock for some six months while planning a move to New York to make a stab at a writing career there, “Masters of Atlantis” was published, and I bought a copy at WordsWorth. As it happened, Portis lived in the same apartment complex as my parents, and I wrote him a note asking if he would sign my book. He responded by inviting me to have lunch with him at the Town Pump; what prompted that invitation, I do not know.

Perhaps he’d read some things I’d written for [the Little Rock alternative newspaper] Spectrum, or maybe I’d mentioned in my note I was wanting to be a writer in New York and that struck a chord with him. Anyway, we had a nice lunch, he signed my book, and we met a couple of other times before I left for New York. Once I was there, we corresponded and would get together for a beer when I would return home to visit my family.

He was very generous with his encouragement, and I was constantly inspired, even as I settled in New York, by his eccentric output from his outpost in Little Rock. In the novels and in his occasional pieces for the Atlantic, the Oxford American, and the Arkansas Times, his voice was so completely his own but also so familiar to me — my mother was from South Arkansas — it made me think that I, also from the literary boonies of Arkansas, might have something to say that sounded like me and not like Henry James, John Updike or Saul Bellow. It also meant something to me that his name was spoken with awe among a certain subset of the New York literary world.

[Video not showing above? Click here: arkansasonline.com/JenningsPortis/]

Q. Though “Dog of the South” is my favorite Portis, I’d probably submit that “True Grit” is his greatest work and on the short list of genuine Great American Novels. It also seems to me that it’s a great example of what Manny Farber called “termite art” — I would imagine the last thing on Portis’s mind when he was writing was creating some fable that would outlive us all, I imagine he saw it as a story he could write that might sell that was informed by all the voices of lady correspondents he’d edited for the newspaper. Not that he was especially modest — it’s just that great books are rarely authored by people who think of themselves as “great artists.” All of Portis’ books are stories first, aren’t they? They’re would be B-movies, not epics.

A. I hadn’t thought of Portis’s work in relation to Farber’s distinction between elephant and termite art, but I think you’re spot on in mentioning it. To go further into entomological comparisons, I also like that “Dog”’s narrator is a Midge, and Portis’s epigraph in the book from Sir Thomas Browne’s description of “the Tortile and tiring stroaks of Gnatworms” seems a joking riposte to William Styron’s use of a Browne epigraph for the elephantine (in Farber’s terms) “Lie Down in Darkness.”

So, yes, while writers like Styron (or early Styron anyway) were pounding away at the typewriter with perpetuity in mind, I do think story, reader entertainment, and comedy were more important for Portis than any desire to produce a “masterpiece.”

He once told me that the only advice he got from his editor Bob Gottlieb, who worked on all his novels but “Gringos,” was “Charlie, make them turn the page,” and I think he was aware of creating an enjoyable reading experience through such narrative craft as pacing and action. While he’s often writing about seemingly small things—internal combustion engines, the etiquette of “saving seats,” “Arklatex folkways”—the quality of his mind and imagination and the depth of his knowledge (worn lightly) transforms his work into art. Like any truly great writer, he had a firm idea of the way he wanted his work to appear before a reader. That care is most apparent in re-reading him, which never gets old to me. I’m always finding new gems.

Q. Portis’ oft-quoted line about Arkansans not being able to achieve “escape velocity” might apply to you, though Little Rock isn’t exactly the cultural boonies. Our mutual friend Bill Jones has this theory about Little Rock being something like London in the 1660s, someplace that punches far above its bantam weight in terms of cultural relevancy and while we might be flattering ourselves I will say that there’s something special here. The question packed in there is, I guess, why are you (back) here?

A. As I mentioned earlier, I was here for about six months in 1985, which is when I started writing for Spectrum, doing a little reporting and a lot of reviewing of books and movies.

When I moved to New York, I could usually see films a week before they opened in Little Rock. Spectrum paid me $15, which meant I just about broke even with a New York movie admission and a box of Goobers. Foremost in my mind was a desire to write, but I was never prolific enough to make a living solely from writing. After about a year of working at the Metropolitan Museum’s gift shop, I sold a piece to Sports Illustrated and subsequently was hired as a reporter, an entry-level position that primarily entailed fact checking. That’s where I really learned whatever journalism chops I now have.

The editing track was more accessible than the writing one at the magazine, so I pursued that, which also allowed me to write regularly. That led to a job as features editor at Tennis magazine, then editorial posts at Time Out New York, Artforum, and Elle Décor. I wrote for all those publications and did other freelance writing as well, often about Arkansas, since no one in New York knew anything about it.

At one time, in 2000, I worked on a book proposal about the 1919 Elaine race massacre (my grandfather lived in West Helena at the time of the violence) and did a lot of archival research in the New York Public Library, but I abandoned the project when I heard that the late Grif Stockley was also working on one; being on the ground in Arkansas and being steeped in the Delta gave him an authority I could not hope to match.

But I knew I wanted to write something substantial about Arkansas and about Little Rock, my own home ground. I pondered topics before finally settling on a “Friday Night Lights ”treatment of Central High’s football team during 2007, the fiftieth anniversary of the integration crisis. My agent sold the book proposal for what eventually became “Carry the Rock,” which was published in 2010 by Rodale and which the University of Arkansas Press reissued this month with a new preface by me.

That was the professional reason for returning, but there was another important reason that led me back to Little Rock and what leads many others back home anywhere — family. My brother and mother died within six months of each other at the end of 2006, and my father was alone for the first time in 52 years. (My sister and her family live near Dallas.) So I rented an apartment in the same complex where my father — and Portis — still lived, researched Little Rock and Central High history every morning, attended football practice every afternoon and games on weekends, and checked on my father every day. It was a little more than four years from the idea for the book to publication.

I had a great career in publishing in New York, and I have no regrets about my two decades there, but let me say that moving home to Little Rock provided me with greater career and personal and creative riches than I can count. I spent hours and hours with my dad in the last decade of his life, until he died at age 95. I met my wife while we were both attending Christ Episcopal Church, where I’d been baptized in 1958, and we now have a daughter, who was baptized there in 2019. For six years, I was a part-time editor at the Oxford American, working with some of the best writers in the country, and the magazine supported two Portis projects, a “Norwood” 50th anniversary variety show and a “True Grit”50th anniversary weekend, with panels, screenings, and an all-star closing evening with Calvin Trillin and Iris DeMent among others.

And I got to sit at the Faded Rose every week with Portis and other regulars, many like Portis sadly gone now, who provided bar patter nonpareil. None of this would have happened had I decided to remain in New York. Something about giving up career striving freed me to craft my own career rather than measuring myself against my peers in New York.

As for punching above its weight, I’d say Little Rock certainly does. (I’ll trust Bill on the comparisons with 1660s London.) Where New York sets up walls or velvet ropes around its artists, so that you have to be invited in, if you ever are, Little Rock’s creative community is an open bazaar where you’re often standing next to or having a beer with or chatting with after listening to a set from or purchasing art from the people you most admire.

You go to a show at The Rep (run by Will Trice, who returned home from New York) and see gorgeous tapestries there by C.C. Mercer (who returned home from Ghana). You go to a show at the Undercroft (Christ Episcopal Church’s intimate music venue) and hear and then talk to Justin Peter Kinkel-Schuster (not a Little Rock resident but close) and he later sends you a painting he did because he wanted to give you one of his Portis-image T-shirts but had run out. You meet world-class architecture photographer Tim Hursley and he invites you to his studio and when you later admire an image he posted on Facebook, he asks if you want him to make you a print when he has one made for himself in New York. It’s now hanging in your office along with the Kinkel-Schuster and a framed poster, autographed by Mavis Staples, from her show in Christ Episcopal’s sanctuary, which happened because you saw her on the Colbert Show one night and mentioned to Rev. Scott Walters that it would be cool if she played in the church and then it happened.

At a friend’s house in L.A., when some other guests find out you’re from Little Rock, they ask a little breathlessly if you know Kevin Brockmeier and you do because Little Rock is little. I could go on — about writer Frederick McKindra, painter Delita Martin (who once lived in our house), novelists Trenton Lee Stewart and Mark Barr — because these things happen all the time and they seem remarkable only in retrospect, when people from other places tell you they are remarkable.

Q. What challenges did you have in editing the Library of America’s volume on Portis? And is there any more unpublished Portis material that needs to be published?

A. To be frank, the staff at the Library of America did the lion’s share of the task of assembling the texts. I made an argument for including more of the civil rights reporting than originally had been chosen and for including all of the early long-form journalism, the “Essays,” one of which had been left out. To keep it to one volume, it was necessary to leave out his play, “Delray’s New Moon.” Since he’s not known as a dramatist and since it’s only been produced once, that seemed reasonable, and the completist can still find it in “Escape Velocity.” I hope someone else will produce it again.

My main job was assembling the “Chronology,” or the biographical timeline, which in the case of Portis was a difficult task because of his lifetime wanderings and his reluctance to speak to journalists or others who might want to trace his life. The Portis family made this much easier by giving me access to the papers he left, which were more extensive than anyone, including the family, knew until died: correspondence with friends and editors and agents, versions of different manuscripts, even gas receipts, which were perhaps the most helpful in tracing his early travels. (I’m writing more about this for the Library of America website.)

A friend and Portis aficionado and collector who knows the movie business, John Parlante, had done some research on Portis’s work in Hollywood, in which Portis was more involved than I suspected, and that helped explain some of the decade-long gap between “True Grit” and “The Dog of the South.” Then assembling that information and writing it up in the style of other Library of America chronologies was a puzzle until I got in a groove. It stands now as the most complete timeline of his life and career but I’m sure someone will want to do something more comprehensive.

The staff at the Library of America and particularly editor Jim Gibbons did most of the notes, which I learned a lot from, such as the legend that sleeping with chihuahuas in your room is an old folk remedy for treating asthma. I thought that was some insane thing that Dr. Reo Symes (and Portis) made up, but it apparently has some folktale heritage derived from the Aztecs. (Snopes.com has rated the treatment as False: https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/chihuahuas-asthma-cure/). I added some notes that ware particular to Arkansas, like the subtle joke in “Dog” where he groups Little Rock in with Geneva and Tokyo as watchingmaking centers, Little Rock having once been a manufacturing hub for Timex. And of course, there was the infinite pleasure of simply rereading all of the novels—to look for typos and such in first editions for the notes and bibliographical information. Their editors and copyeditors were already on this, but it was a good excuse to re-read everything.

Q. How do you think Portis would feel about being canonized in the Library of America?

A. I think he would be very pleased, not necessarily with the idea of being in a “canon” but that his novels and other stories will be available for readers to enjoy, “in perpetuity” as is the LoA’s aim. As much as he had a reputation for avoiding the spotlight, like every writer he always wanted readers, made a regular effort to respond sensitively to readers who wrote to him, and always appreciated efforts to bring his work to a wider public. As he said when I asked him about republishing some of his journalism and other work in “Escape Velocity,” his main concern was that the work “hold up,” that it didn’t seem dated or trivial. The Library of America volume shows that almost everything he wrote meets that very high standard for lasting value that he set for his work.