Efforts to ban books nearly doubled in 2022 over the previous year, according to a report published Thursday by the American Library Association. The organization tracked 1,269 attempts to ban books and other resources in libraries and schools, the highest number of complaints since the association began studying censorship efforts more than 20 years ago.

The analysis offers a snapshot of the spike in censorship but most likely fails to capture the magnitude of bans. The report is compiled from book challenges that library professionals reported to the association's Office for Intellectual Freedom, and it also relies on information gathered from news reports.

Book removals have exploded in recent years and have become a galvanizing issue for conservative groups and elected officials. Fights over what books belong on library shelves have caused bitter rifts on school boards and in communities and have been amplified by social media and political campaigns.

"I've never seen anything like this," says Deborah Caldwell-Stone, who directs the ALA's Office for Intellectual Freedom. "The last two years have been exhausting, frightening, outrage inducing."

With the increasingly organized campaigns to remove titles on certain topics, books have become a proxy in a broader culture war over issues like LGBTQ rights, gender identity and racial inequality.

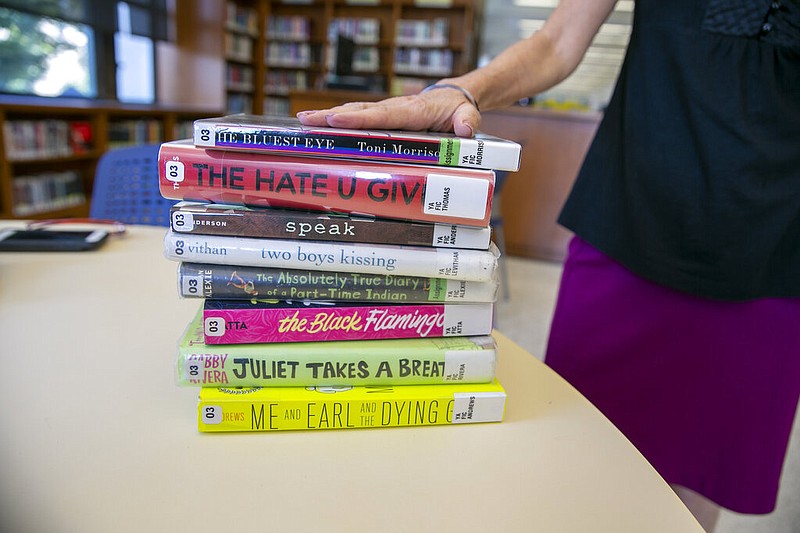

Of the 2,571 unique titles that drew complaints in 2022 -- up from 1,858 books in 2021 -- a vast majority were books by or about LGBTQ people or books by or about people of color, the association found. Many of the same books are targeted for removal in schools and libraries around the country -- among them, classics such as Toni Morrison's "The Bluest Eye" and Margaret Atwood's "The Handmaid's Tale," and newer works such as Juno Dawson's "This Book is Gay" and Maia Kobabe's "Gender Queer."

"Every day professional librarians sit down with parents to thoughtfully determine what reading material is best suited for their child's needs," ALA President Lessa Kanani'opua Pelayo-Lozada said in a statement. "Now, many library workers face threats to their employment, their personal safety, and in some cases, threats of prosecution for providing books to youth they and their parents want to read."

Caldwell-Stone says that some books have been targeted by liberals because of racist language -- notably Mark Twain's "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" -- but the vast majority of complaints come from conservatives. They include Jonathan Evison's "Lawn Boy," Angie Thomas' "The Hate U Give" and a book-length edition of the "1619 Project," the Pulitzer Prize-winning report from The New York Times on the legacy of slavery in the U.S.

Book bans have affected public libraries as well as schools: In 2022, some 60% of complaints that the association tracked were directed at books and materials in school libraries and classrooms, while around 40% of challenges were aimed at material in public libraries.

The development is worrisome for educators and librarians, who have increasingly come under fire for the books in their collections. Some librarians have been accused of peddling obscenity or promoting pedophilia; others have been harassed online by people calling for them to be fired or even arrested. Some libraries have been threatened with a loss of public funding over their refusal to remove books.

Efforts to remove books began to rise during the pandemic, often spreading from one community or school district to another through social media, as lists of books flagged as inappropriate circulated online. The movement has been supercharged by a network of conservative groups -- including organizations such as Moms for Liberty and Utah Parents United -- that have pushed for book removals and have lobbied for new policies that change the way library collections are formed and book complaints are handled.

Increasingly, challenges are being filed against multiple books, whereas in the past, libraries more frequently received complaints about a single title, the group said.

"What the numbers are reflecting to us is that this is a campaign," Caldwell-Stone said in an interview Thursday morning. "What we're seeing is not the result of an individual parent speaking to a librarian or a teacher about a particular book their child is reading. We're seeing a campaign by politically partisan groups to remove vast swaths of books that don't meet their agenda, whether that's a political or religious or moral agenda."

Some librarians and free speech advocates are also alarmed by new legislation that aims to regulate the content of libraries, or the way librarians do their jobs.

Recently, Republicans in the House introduced a "Parents Bill of Rights," proposed legislation that some educational advocacy organizations worry could lead to a rise in book bans. The bill, which was sponsored by Rep. Julia Letlow, R-La., requires that parents have access to "a list of the books and other reading materials available in the library of their child's school."

Some librarians and teachers who are concerned by the spike in book bans argue that the notion of parental rights should not enable a small group of parents to decide what books all other students and families can access.

"We don't quarrel with parents who want to guide their children's reading," Caldwell-Stone said. "What we have a problem with is advocacy groups who rise up and demand that everybody read the books that they approve of and not read any other books, and deny that choice to other families."

Bills facilitating the restriction of books have also been proposed or passed in Arizona, Iowa, Texas, Missouri, Florida, Utah and Oklahoma. In Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis has approved laws to review reading materials and limit classroom discussion of gender identity and race. Books pulled indefinitely or temporarily include John Green's "Looking for Alaska," Colleen Hoover's "Hopeless," and Grace Lin's picture story "Dim Sum for Everyone!"

More recently, Florida's Martin County School District removed dozens of books from its middle schools and high schools, including numerous works by novelist Jodi Picoult, Toni Morrison's Pulitzer Prize-winning "Beloved" and James Patterson's "Maximum Ride" thrillers, a decision which the bestselling author has criticized on Twitter as "arbitrary and borderline absurd."

DeSantis has called reports of mass bannings a "hoax," saying in a statement released earlier this month that the allegations reveal "some are attempting to use our schools for indoctrination."

Some books do come back. Officials at Florida's Duval County Public Schools were widely criticized after they removed "Roberto Clemente: The Pride of the Pittsburgh Pirates," a children's biography of the late Puerto Rican baseball star. In February, they announced the book would again be on shelves, explaining that they needed to review it and make sure it didn't violate any state laws.

Last year, the New York Public Library pushed back on the trend with its "Books for All" campaign, making widely banned titles available on its free electronic reading platform.

"These recent instances of censorship and book banning are extremely disturbing and amount to an all-out attack on the very foundation of our democracy," library President Anthony Marx said at the time.

"Knowledge is power; ignorance is dangerous and breeds hate and division," he said. "Since their inception, public libraries have worked to combat these forces simply by making all perspectives and ideas accessible to all, regardless of background or circumstance."

Information for this article was contributed by Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth A. Harris of The New York Times, by Hillel Itale of the Associated Press and by Peter Sblendorio of the New York Daily News.