LIBBY, Mont. -- Almost 25 years after federal authorities responding to news reports of deaths and asbestos-related illnesses descended on Libby, a town of about 3,000 people near the U.S.-Canada border, some asbestos victims and their family members are seeking to hold publicly accountable one of the major corporate players in the tragedy: BNSF Railway.

Hundreds of people died and more than 3,000 have been sickened from asbestos exposure in the Libby area, according to researchers and health officials. Texas-based BNSF faces accusations of negligence and wrongful death for failing to control clouds of contaminated dust that used to swirl from the rail yard and settle across Libby's neighborhoods.

The vermiculite was shipped by rail from Libby for use as insulation in homes and businesses across the U.S.

The first trial among what attorneys say are hundreds of lawsuits against BNSF for its alleged role polluting the Libby community is scheduled to begin today.

The railroad -- owned by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc. -- has denied responsibility in court filings and declined further comment.

The plaintiffs for the upcoming trial against BNSF, the estates of Joyce Walder and Thomas Wells, lived near the Libby rail yard and moved away decades ago. Both died in 2020 of mesothelioma, a rare lung cancer caused by asbestos that is disproportionately common in Libby.

The mine a few miles outside town once produced up to 80% of global vermiculite supplies. It closed in 1990. Nine years later, the Environmental Protection Agency arrived in Libby and a subsequent cleanup has cost an estimated $600 million, with most covered by taxpayer money. It's ongoing, but authorities say asbestos volumes in downtown Libby's air are 100,000 times lower than when the mine was operating.

Awareness about the dangers of asbestos grew significantly over the intervening years, and last month the EPA banned the last remaining industrial uses of asbestos in the U.S.

Asbestos doesn't burn and resists corrosion, making it long lasting in the environment. People who inhale the needle-shaped fibers can develop health problems as many as 40 years after exposure. Health officials expect to grapple with newly diagnosed cases of asbestos disease for decades.

The EPA declared the nation's first ever public health emergency under the Superfund cleanup program in Libby in 2009. The pollution led to civil claims from thousands of people who worked for the mine or the railroad, or who lived in the Libby area.

During a yearslong cleanup of the Libby rail yard that began in 2003, crews excavated nearly the entire yard, removing about 18,000 tons of contaminated soil. In 2020, BNSF signed a consent decree with federal authorities resolving its cleanup work in Libby and nearby Troy, plus a 42-mile stretch of railroad right-of-way.

Last year, BNSF won a federal lawsuit against an asbestos treatment clinic in Libby that a jury found submitted 337 false asbestos claims, making patients eligible for Medicare and other benefits. The judge overseeing the case ordered the Center for Asbestos Related Disease to pay almost $6 million in penalties and damages, forcing the facility into bankruptcy. It continues to operate with reduced staff.

Some asbestos victims viewed the case as a ploy to discredit the clinic and undermine lawsuits against the railroad. BNSF said the verdict would deter "future misconduct" by the clinic.

In the months leading up to this week's trial, attorneys for BNSF repeatedly tried to deflect blame for people getting sick, including by pointing to the actions of W.R. Grace and Co., which owned the mine from 1963 until it closed. They also questioned whether other asbestos sources could have caused the two plaintiffs' illnesses and suggested Walder and Wells would have been trespassing on railroad property.

U.S. District Court Judge Brian Morris blocked BNSF from blaming the conduct of others as a means of escaping liability, and he said the law doesn't support the notion that trespassing reduces a property owner's duty not to cause harm.

Morris has yet to issue a definitive ruling on another key issue: the railroad's claim that its obligation to ship goods for paying customers exempts it from liability.

The plaintiffs argue the rail yard in downtown Libby was used for storage and not just transportation, meaning the railroad is not exempt.

Montana's Supreme Court has ruled in a separate case that BNSF and its predecessors were more involved in the mine than simply shipping its product.

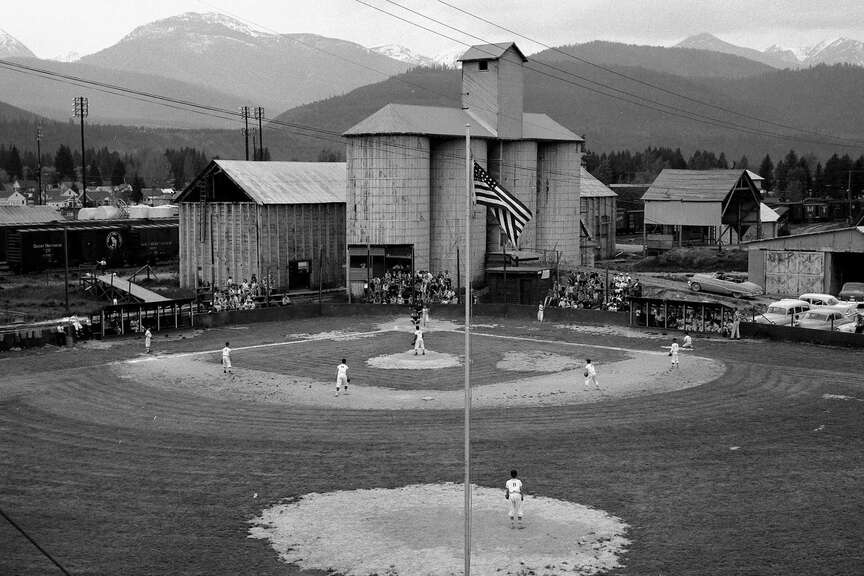

This photo from the 1960s shows a baseball field next to a railyard in Libby, Mont., where asbestos-tainted vermiculite was stored after being mined from a nearby mountain. Thousands of people have been diagnosed with asbestos-related illnesses from exposure in the Libby area. A trial starts Monday in a lawsuit against BNSF Railway from the estates of two people who used to live in Libby and died from mesothelioma, a rare lung cancer caused by asbestos exposure. (The Western News via AP)

This photo from the 1960s shows a baseball field next to a railyard in Libby, Mont., where asbestos-tainted vermiculite was stored after being mined from a nearby mountain. Thousands of people have been diagnosed with asbestos-related illnesses from exposure in the Libby area. A trial starts Monday in a lawsuit against BNSF Railway from the estates of two people who used to live in Libby and died from mesothelioma, a rare lung cancer caused by asbestos exposure. (The Western News via AP) Paul Resch is seen petting his dog Mr. Bojangles after taking a walk near Parmenter Creek, Thursday, April 4, 2024 near Libby, Mont. Resch has an asbestos related disease that's severely scarred his lungs. He tries to stay in shape to keep his breathing capacity from deteriorating. As a child Resch played baseball on a field constructed out of asbestos-tainted vermiculite and used to play inside storage bins for the material at Libby's railyard. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown)

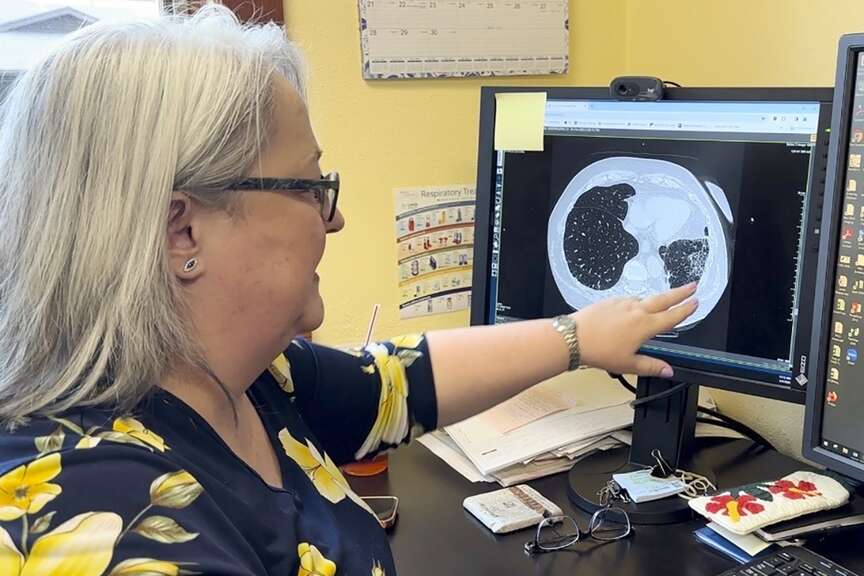

Paul Resch is seen petting his dog Mr. Bojangles after taking a walk near Parmenter Creek, Thursday, April 4, 2024 near Libby, Mont. Resch has an asbestos related disease that's severely scarred his lungs. He tries to stay in shape to keep his breathing capacity from deteriorating. As a child Resch played baseball on a field constructed out of asbestos-tainted vermiculite and used to play inside storage bins for the material at Libby's railyard. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown) Dr. Lee Morissette shows an image of lungs damaged by asbestos exposure, at the Center for Asbestos Related Disease, Thursday, April 4, 2024, in Libby, Mont. The Libby area was contaminated by asbestos-contaminated vermiculite from a nearby mine that was shipped through by rail. The town has been largely cleaned up, but health officials say the long latency period for asbestos-related diseases means people will continue to be diagnosed with illnesses for years. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown)

Dr. Lee Morissette shows an image of lungs damaged by asbestos exposure, at the Center for Asbestos Related Disease, Thursday, April 4, 2024, in Libby, Mont. The Libby area was contaminated by asbestos-contaminated vermiculite from a nearby mine that was shipped through by rail. The town has been largely cleaned up, but health officials say the long latency period for asbestos-related diseases means people will continue to be diagnosed with illnesses for years. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown) FILE - The W.R. Grace vermiculite mine is shown, outside of Libby, Mont., Feb. 17, 2010. Libby, a town of about 3,000 along the Kootenai River, had widespread contamination from asbestos-tainted vermiculite that was stored in town and transported by rail across the U.S. for use as insulation and other purposes. Contamination in the town has been cleaned up but the mine has not been addressed. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File)

FILE - The W.R. Grace vermiculite mine is shown, outside of Libby, Mont., Feb. 17, 2010. Libby, a town of about 3,000 along the Kootenai River, had widespread contamination from asbestos-tainted vermiculite that was stored in town and transported by rail across the U.S. for use as insulation and other purposes. Contamination in the town has been cleaned up but the mine has not been addressed. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File) FILE - The town of Libby, Mont., is seen Feb. 17, 2010. Thousands of people have been sickened and hundreds killed by asbestos contamination in the Libby area. Most of the contamination has been cleaned up but the long latency period of asbestos-related diseases means people continue to get diagnosed with illnesses. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File)

FILE - The town of Libby, Mont., is seen Feb. 17, 2010. Thousands of people have been sickened and hundreds killed by asbestos contamination in the Libby area. Most of the contamination has been cleaned up but the long latency period of asbestos-related diseases means people continue to get diagnosed with illnesses. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File) Paul Resch is seen speaking about growing up in northwestern Montana, on Thursday, April 4, 2024, near Libby, Mont. Resch is among thousands of people diagnosed with asbestos-related diseases from contaminated vermiculite that was mined near Libby. The material was shipped by rail to destinations across the U.S. for use as insulation. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown)

Paul Resch is seen speaking about growing up in northwestern Montana, on Thursday, April 4, 2024, near Libby, Mont. Resch is among thousands of people diagnosed with asbestos-related diseases from contaminated vermiculite that was mined near Libby. The material was shipped by rail to destinations across the U.S. for use as insulation. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown)