« 1902 »

Established in 1902 in an effort to improve the Arkansas penal system, Cummins Unit, also known as the Cummins Prison Farm, is the oldest and largest of the state’s prison farms, where inmates produce crops and raise livestock.

A maximum-security prison covering more than 16,000 acres in Lincoln County, it was founded as an alternative to the convict lease system, which entailed the state contracting with private companies that used prison labor. Prisoners did jobs inside and outside the prison facilities, but after mounting concerns over abusive treatment and miserable conditions, the camps where leased prisoners were held were subjected to inspections beginning in 1890.

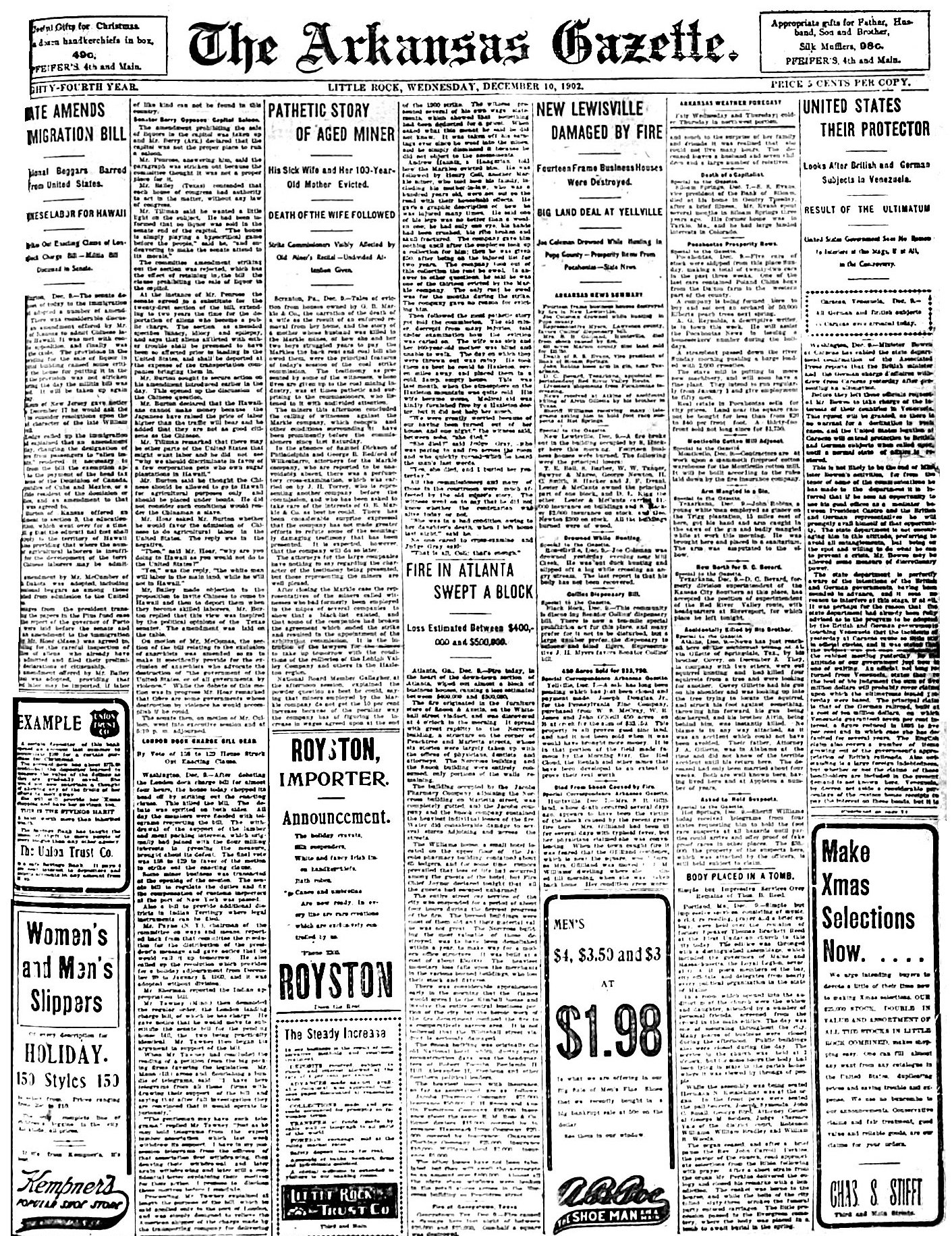

In 1902, the state bought 10,000 acres for the new prison farm, including land from the Cummins and Maple Grove plantations. The first prisoners, about 100 men, were moved from the Little Rock penitentiary on Dec. 10, 1902, as this Page 2 of The Arkansas Gazette reports. The article also explains that the prisoners would be transported on the Arkansas River via the steamer A.D. Allen instead of by rail, as this was a less expensive way to travel the 135 miles.

The Gazette reports plans for the prisoners to “erect temporary stockades” until the state fully occupied the land Jan. 1, 1903. After that, permanent structures would be built to house a “concentration of about all the state convicts … except those on the Dickinson contract,” and the few left in the Little Rock penitentiary. The Dickinson contract was the private contract currently in place under the convict lease system and it “came to symbolize all the evils embodied in convict leasing — the lease was too long, the payment to the state was too small, and state control was too limited,” according to Calvin R. Ledbetter Jr.’s The Long Struggle to End Convict Leasing in Arkansas.

The convict leasing system wasn’t made illegal until 1913, and much of the corruption and mistreatment continued into the prison farm model.

The year 1902 marked a genuine turning point in another area of Arkansas culture. On July 1, Judge Carrick White Heiskell of Memphis and his sons, John Netherland and Frederick, partnered with Gazette business manager Fred Allsopp to buy a controlling interest in the Gazette Publishing Co.

The judge left the running of the paper to his sons; and so with his brother as managing editor, J.N. Heiskell began his life’s work as editor of the Arkansas Gazette. Mocked early on as “the high school boys,” the brothers transformed what had been a political party mouthpiece with advertisements plastered across its front page into a modern newspaper that prioritized news.

— Jeanne Lewis and Celia Storey

You can download a PDF by clicking the image, or by clicking here.