Sturgis Plaza, in Little Rock's downtown River Market District, is lovely this time of year. With mild weather and budding foliage, it welcomes resident families and wide-eyed visitors alike to stroll its winding pathways parallel to the voluptuous Arkansas River.

You almost miss the most important spot on the Plaza, historically speaking, that is. A stump of calico-colored stone juts out of the pavement, the looming Junction Bridge draping, visually, like an iron stole across its diminutive shoulders. It's the most important rock for a thousand miles upstream or downstream, stubby though the chunk may be.

It's La Petite Roche, "The Little Rock" or a piece of it anyway, hewn from the landmark riverbank formation and outfitted with a plaque explaining its significance. Today, many visitors reach the rock by smartphone, following GPS maps to a digital mark on a screen. But three centuries ago, La Petite Roche was the mark beckoning safe harbor to American Indian watercraft and, inevitably, the European and American boats to follow.

"You think about 300 years, that's not an insignificant amount of time," says Denver Peacock, founder of The Peacock Group and chairman of the La Petite Roche Tricentennial Task Force, which was formed to commemorate the 300th birthday of its discovery by European explorers.

[RELATED: La Petite Roche Tricentennial events]

"We're not trying to mark the history of Little Rock as a capital or as a town. This is about marking the first historical reference that we have to our namesake. This was a French claim originally, but ultimately, it led to who we are today as a thriving, progressive, diverse city, a capital city."

Peacock assembled a group of like-minded historical experts, museum leaders, tourism types and other interested parties to the volunteer task force. The group has put together programming in April, both collectively and independently, and has reached out to other local organizations in the hopes they will seize upon the theme of the anniversary with events of their own throughout the year.

"The response has been overwhelming," Peacock says. "There were some people who were at least somewhat aware of this discovery and a lot of folks who, as soon as they heard about it, said, 'Oh, yeah. That's a really cool thing. I'm glad you guys are doing it. How can I help?' I can't think of anyone who flat-out said, 'No, we don't want to do anything with this.'

"We have many people who are still trying to figure out how they're going to mark it or honor this anniversary year, but we hope this ultimately will be a year of activities and events people can enjoy in honor of this historical milestone in their own way."

Scott Whiteley Carter, Little Rock public affairs and creative economy adviser, is also the city's official historian. As part of the task force, he says he'd ideally want the saga of La Petite Roche to be told from a variety of viewpoints during the year.

"To me, what's exciting about this whole opportunity with the tricentennial is there are some programs and some speakers, and that's wonderful, but I think it also can start an ongoing conversation in ways that have not happened in the past," he says. "Let's talk about 300 years of the good, the bad and the ugly. This is the time to do it."

Denver Peacock is founder of The Peacock Group and chairman of the La Petite Roche Tricentennial Task Force. (Courtesy of TPG)

Denver Peacock is founder of The Peacock Group and chairman of the La Petite Roche Tricentennial Task Force. (Courtesy of TPG)

ONCE UPON MILLENNIA

Like all geological formations, La Petite Roche was around for multiple millennia before it got the name that grew into a settlement that ripened into a city. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas notes the outcropping occurs where the foothills of the Ouachita Mountains first touch the river, creating a natural plateau above the floodplain. The rock, sandstone, was originally deposited about 300 million years ago, part of what geologists call the Jackfork Formation.

The modern history of the rock begins with Jean-Baptiste Benard de la Harpe, a French explorer whose party traversed the Arkansas River in 1722. On April 9, la Harpe noted the "rocks sticking out of the ground." He floated right by the first one, so taken was he with a soaring bluff to the north of a river bend yonder, quickly dubbing that one Le Rocher Francais or The French Rock, now known as Big Rock.

That's right — contrary to popular belief, la Harpe initially didn't pay enough mind to the first outcropping to name it. Rather, "Le Petit Rocher" was more or less christened informally as a navigational reference, a term used to distinguish one outcropping from another. The name first appeared on a map in 1799, per a history penned by Bill Worthen, retired director of Historic Arkansas Museum. As to why the settlement to follow wasn't called "Big Rock," Worthen writes that what Le Petit Rocher lacked in mass, it made up for in positioning.

"To extend The Little Rock's significance, should one begin a journey north by watercraft at the mouth of the Mississippi River and hang a left into the channel of the Arkansas, the very first rock one would see, after a journey of over 700 miles, would be The Little Rock," Worthen notes, adding that "little" likely didn't align with the images conjured in the modern mind.

"Yes, they had a 'big' in mind when they used 'little,'" he writes.

While the actual dimensions of the landmark are lost to times and tides, several things about it are not in dispute. One, Le Petit Rocher (per the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, it wouldn't be recast in the feminine case, La Petite Roche, until the 1950s) formed an excellent natural harbor and a firm footing for future construction as the city grew up.

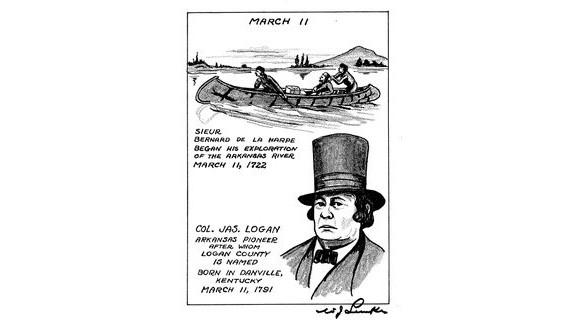

A poster of the pictorial history of the founding of “The Little Rock.” (Courtesy of the Arkansas State Archives/Walter J. Lemke Collection)

A poster of the pictorial history of the founding of “The Little Rock.” (Courtesy of the Arkansas State Archives/Walter J. Lemke Collection)

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

"There is a reason that Little Rock grew up there and was established in this area instead of 30 miles up or 30 miles down the Arkansas River," Carter says. "It was that natural harbor and the fact that the land was elevated — unlike north of the river, which flooded easily, south of the river you could fairly easily climb up the bank. There are reasons that we developed in the way that we did. It's not just coincidental."

Exploration begat the settlement in 1820 and over the next 200-plus years, La Petite Roche was central to the area's development. From bawdy cargo traffic and steamboat moorings downstream to the arrival of the railroad and finally automobiles, the rock literally anchored the march of the city's progress.

Which brings up another historical truth — that being that the very progress the formation supported and made possible is nearly what condemned it to the bottom of the river or the gravel pile. Those seeking to tame or span the river wasted little by way of sentimentality when it came to La Petite Roche, as evidenced by an ill-fated bridge project that very nearly shaved the city's namesake to nothing.

"Several tons of rock have been cut away and thrown into the river, so much so as to greatly change the appearance of the rock from the lower side," Worthen's essay quotes from an October 1872 account in the Arkansas Gazette. The paper would go on to plead for someone "to take a photograph of the 'Little Rock,' from which our city derives its name, before it is destroyed by the ruthless hand of civilization."

The ultimate indignity of the episode was that, after this considerable reduction of the landmark, the bridge was never built. Not unlike the wholesale slaughter of the Arkansas bear, quail or buffalo in frontier times, the incident represents a squandering of natural heritage and resources that still strikes a nerve.

"When we were working on the La Petite Roche Plaza in 2008 and 2009, many people were like, 'Oh, it's horrible that the railroad companies blasted away part of The Little Rock,'" Carter says. "No one thought about preserving natural landmarks at the time, not just here but anywhere."

[RELATED: La Petite Roche Historical Timeline & Quotes from Arkansas Notables]

AN INDIGENOUS PRESENCE

Just as the formation itself sat for thousands of years before white settlers arrived, so too were native tribes first here by generations. Members of the tricentennial task force are careful to acknowledge that fact in discussing the anniversary.

"We are on historical tribal homeland," says Dr. Daniel Littlefield, director of the Sequoyah National Research Center at University of Arkansas at Little Rock. "All of the high places on the river in this part of the world are. Memphis, for instance, was the site of a Chickasaw settlement and part of that is still called Chickasaw Bluffs. Natchez was a high place, on the Mississippi side, around Vicksburg. On the Arkansas side, Arkansas Post, Pine Bluff, all of these high places, particularly in the Delta area, were places of settlement where they could get above the water.

"They could see people coming and going, river traffic and so on. There were all kinds of logistical reasons and safety reasons why they would encamp on those high places. So yes, there were settlements here, not even a question about that."

In Little Rock's case, the resident tribe was the Quapaw, who got along well with the explorers and with the waves of whites that came after.

"The Quapaw were known, and have been known through history, as a peaceful people," Littlefield says. "I can't name a conflict that happened between Europeans and the Quapaw. There just was no hostile kind of interaction at all."

In fact, once permanent settlers started arriving, the two communities mingled to the point of intermarrying although, as Littlefield points out, that activity varied along social and particularly religious lines.

"The Catholics' approach to dealing with American Indians was different from the way Protestants dealt with them," he says. "The Catholics simply took them as they were and said, 'Zap, you're a Catholic,' and went on and intermarried. That was something that the Protestants were hesitant to do. It happened, but they were hesitant to do it. Their relationship was more conflicted."

Ultimately, however, the fate of the sovereign Quapaw was to be the same as countless other tribes throughout what became the United States. Through one broken treaty after another, the tribe was packed up and moved to areas outside of their native homeland and even here, The Little Rock was pressed into playing a part. Encyclopedia of Arkansas notes that in 1818, the United States restricted the tribe to an Arkansas reservation, the western boundary of which — known as the Quapaw Line — began at La Petite Roche, also called the Point of Rocks, and extended due south.

"Arkansas Territory pushed them west of their more traditional lands in that treaty in 1818 and then in 1824, they took the rest of Quapaw land and sent the Quapaws down on the Red River into Louisiana to join the Caddos," Littlefield says. "Well, the Quapaws kept coming back and a group of them settled around Pine Bluff, south of Altheimer.

"Finally, in 1833, there was a third treaty that moved them to an area up in the very northeastern corner of what is now Oklahoma. It was a piece of land that the Cherokees had given up so that various small tribes could be settled there. That's where they were settled and that's where they still are today."

Littlefield, who will deliver a talk during the April festivities on the removal of Arkansas' native people, says it's as important to tell the American Indian experience as it is to trace the city's growth and development emanating over the generations after la Harpe's expedition.

"I think it's rare that a state has the opportunity to know about the role it played in such a significant national event as Indian removal and the results of that," he says. "We have, in the public mind, a stereotype of not only that event and of the Trail of Tears, but also a stereotype of American Indians. It's important that the younger generations particularly understand that it's a much more complex story. I think it's important that we understand that if we're really going to know the history of our state."

BICENTENNIAL OVERSIGHT

Little Rock's observance mirrors that of other cities — as Carter points out, over the last decade Santa Fe turned 400, San Antonio and New Orleans both celebrated tricentennials and St. Louis marked 250 years. But there's a bigger motivation here than just keeping up with the Joneses, as Peacock notes. La Petite Roche's 200th anniversary passed without so much as a speech or proclamation, a lack of pomp derided mightily two decades later by Arkansas Gazette editor and owner J.N. Heiskell.

"Heiskell was discussing in Little Rock what he felt was a lack of awareness about our place in history and its importance," Peacock says. "In a speech he said, 'The 200th anniversary of the discovery of our rock was allowed to pass absolutely unnoticed. If the year 2022 should pass with no proper observance of the tricentennial of the discovery of the historic rock, don't say I didn't warn you.'"

At that, Peacock chuckles.

"Our response to Mr. Heiskell will be, 'We listened to you, we heard you and we will not let the 300th anniversary pass without a proper observance," he says. "All of us, from both sides of the river, will together over the next year present a visual reminder to Mr. Heiskell that we are taking his challenge to heart. And we hope that 100 years from now, the next generation will do the same."