In autumn 1919, the Arkansas Gazette discovered the existence of a most unusual widow, Mrs. Tennessee Frances Scott Peppers. We know she was a widow by the way they handled her name.

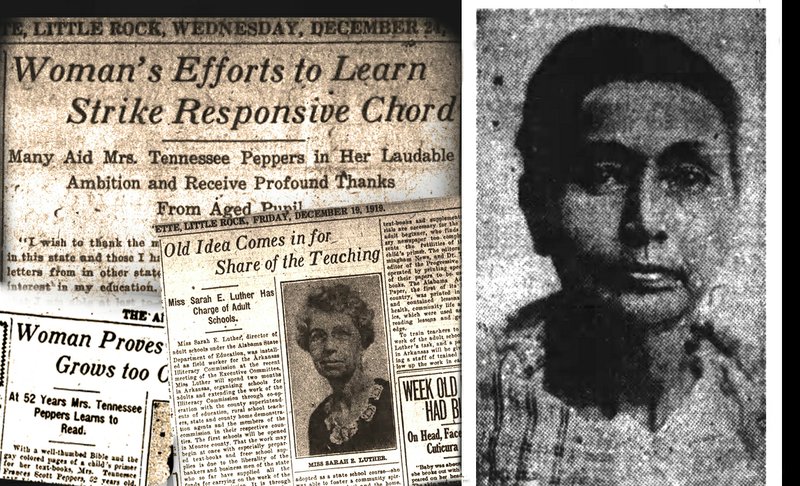

So unusual was she that the story about her included a photograph. It was on Page 4 Oct. 29 beside Nell Cotnam's society column, "Social and Personal," and I suspect Cotnam wrote it. That space often published stories about inspiring female achievers.

Mrs. Peppers was a true achiever. As headlines put it, she was an "Aged Pupil" who proved that "One Never Grows Too Old to Learn."

At the astonishing age of 52 ...

I'm sorry.

Ahem.

At the astonishing age of 52, she was learning to read.

Today, 52 is not antiquity. But in 1919, this crone was something like Methuselah. Learning to read at that age? A woman? Unheard of.

With a well-thumbed Bible and the gay colored pages of a child's primer for her text-books, Mrs. Tennessee Frances Scott Peppers, 52 years old, 1715 Lincoln avenue, is teaching herself to read.

Born just before or maybe during the Civil War (sources conflict), she was brought up in a log cabin on a mountain farm near Nashville, Tenn. Her family lived on income from corn and millet crops, and farm chores took precedence over schooling. The truck garden was "Tenny" Scott's special care. Despite stony ground, she raised sweet potatoes of wonderful size.

The red schoolhouse in those days was far away at the cross roads and in the short winter season it was almost impossible to get through the mountain trails.

When she was 17, the family moved to Arkansas, settling near Jonesboro. From other sources, I believe she married Andrew J. Peppers in 1888 when she was 19. The Pepperses adopted a boy to raise along with their own son, and the two kids and farm work took all of her attention. But she made sure both boys attended grammar school.

Andrew seems to have died in 1913.

The story doesn't say that he died, only that her sons were married and her house was empty and she was determined to make up for lost time.

"I know all the alphabet," she said proudly — and indeed she did, with a glibness and surety that would put to shame some of the more modern products of the phonetic system — "And I can read off some words. I always wanted to be able to read the Twenty-third Psalm. And hymns, too! I just have to sing along now from what I can remember."

She was keenly interested in education:

"I'd like to have had my boys go to this new sort of school — the Junior High School," she said. "It must be so nice. In my days they didn't have so many schools. When you finished the high grade, you were through. But now-a-days they learn a lot more."

She knew about a night school for adults offered in Little Rock, but she was slightly lame and unable to walk so far alone. So she studied by herself as best she could with the help of a little boy. She was fond of gardening and flowers and piecing quilts, but her main absorption was the puzzling differences between "n" and "m," and "b" and "d."

Other newspapers picked up her story, including the Buffalo Evening News, St. Louis Post-Dispatch and The Philadelphia Inquirer. And the story didn't end there.

GREETINGS

On Christmas Eve 1919, the Gazette printed a letter from Mrs. Peppers, written by her son at her dictation:

I wish to thank the many friends in this state and those I have received letters from in other states, for their interest in my education. I can say that I am able at last to read my favorite chapter in the Bible, the Twenty-third Psalm. I am also learning to sing the song by the title, "No, Never Alone." Wishing you a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.

Mrs. Zella Hargrove Gaither of 1518 State St. had been visiting her three times a week to give her "professional lessons" in reading. After 12 lessons, she could read that psalm.

Someone sent her a new large-print Bible, and anonymous others had sent two primers. Another unnamed philanthropist — in Boston — sent a box of anagrams.

Mrs. Peppers also had entertained an important visitor: Miss Sarah E. Luther, state director of adult schools in Alabama, who was the newly appointed field agent for the Arkansas Illiteracy Commission.

REAL-WORLD PROBLEMS

Learning to read at 52 is a huge achievement today, too, requiring courage and humility. Although vast strides have been made since 1919, Arkansas lags behind the reading rates of wealthier states. According to statistics gathered in 2015 and quoted by the Adult Learning Alliance of Arkansas, 13.7% of Arkansans age 16 or older lack basic literacy skills. But there are resources that help adults learn, the Arkansas Literacy Councils.

A good place to look for them is under "Local Programs" on the alliance website, arkansasliteracy.org. Or call (501) 907-2490.

The Legislature created the Illiteracy Commission in 1917, but its work didn't really get going until 1919, after the Great War. It had eight unpaid members, men and women, and the state superintendent of public education was an ex-officio member.

The commission began a fundraising drive focused on bankers. In the May 1919 issue of The Arkansas Banker, Superintendent J.L. Bond explained that the commission had "declared War" on illiteracy.

It was decided that the commission should get out special lessons for the use of volunteer teachers in their work of teaching illiterates to read and to write. During the teacher's institutes hundreds of teachers, both white and colored, volunteered to teach "moon-light" or ''evening" schools for ten days or more for the purpose of teaching the adult illiterates in their respective districts at least to READ and WRITE.

Luther was training Arkansas teachers to lead these adult schools — the schools Mrs. Peppers was unable to limp to.

Bond wrote that the commission's first acts included creating an Auxiliary Illiteracy Commission to help black adults read. Every last thing was segregated in those days. Here is my favorite part of Bond's article:

Some fine work has been done, but it has been impossible for this office to tabulate or report concretely all the work that has been done for the reason that we were not able to get the reports from all the teachers that did work of this kind.

He added the campaign's two goals: the ultimate goal was eliminating illiteracy or, as he put it, the rout of the enemy. But the immediate goal was preparing for the 1920 Census.

Here comes the heartwarming part.

Look up Tennessee Peppers on Ancestry.com — try spelling her name "Tennie C" — and you'll learn that life eventually took her to San Bernardino, Calif., where, in 1952, she died. But for that 1920 Census, she was in Little Rock.

The Gazette was wrong about her house being empty. She lived with her 21-year-old son, Clinton Mobley Peppers, his wife and Clint's 4-year-old brother-in-law. Clint was a truck driver for the city street department.

Census records are troves of information correct and incorrect, but two answers on the line for Tennie Peppers are worth believing:

Could she read? "Yes."

Could she write? "Yes."

Email:

cstorey@adgnewsroom.com

Style on 12/23/2019