With April flowers obliterated by May showers, Dear Reader will not be amazed to hear that Arkansas was damp 100 years ago today. Damp and then some. Heavy rain over the weekend "did not do anything good," as the Arkansas Gazette put it May 17, 1920. It wasn't a great enough storm.

Rivers across the state were swollen. Temperatures were in the 50s and 60s. The first cutting of alfalfa was lost; cotton, corn and oats were damaged; the Irish potato outlook was very gloomy. But apples were OK in the Northwest.

Dumas in Desha County received 7.19 inches that Saturday and Sunday.

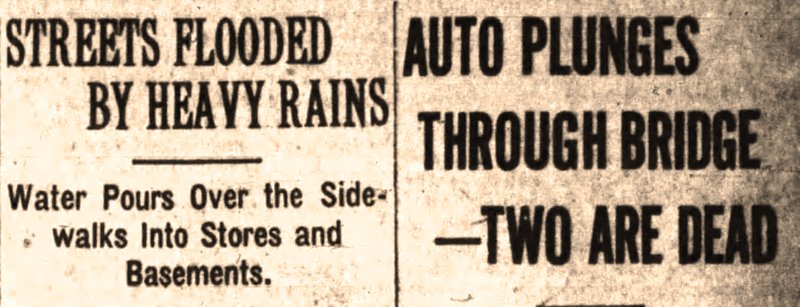

The Arkansas Democrat reported that steel bridges were down at Womble, Caddo Gap, Glenwood and Amity. Subsiding waters revealed their piers twisted into masses of I beams, rods, tree trunks and driftwood half buried in sand and gravel:

Cotton houses and plows and other farm implements are seen here and there hanging high in trees. Wire fences by the mile are meshed up all along the river like war barricades. Whole fields on which corn was knee high are buried in places with two feet of rich new soil and in other places scoured down to show the plow prints of years gone by.

Levees broke in five places at Lewisville in Lafayette County. On May 19, word came that Mr. and Mrs. W.O. Haynes and the Rev. W.C. Scott, pastor of the Methodist Church at Lewisville, were rescued after being marooned 36 hours on an island in the Red River.

These were not deadly floods. It was just a sodden spring. But at least two people died in the storm.

Two Army officers were killed at Little Rock when their car dove off a known traffic hazard: the Lincoln Avenue Viaduct.

The viaduct stood where today’s Lincoln Avenue Viaduct stands, at the bend of Arkansas 10 where LaHarpe Boulevard flows into Cantrell Road.

They were dignitaries in town from a U.S. Army remount station at Camp Taylor, Ky. They and a third officer, who was severely injured in the crash, had judged a big horse show Saturday at Camp Pike's remount station in North Little Rock. (Aside to Puzzled Reader: If you will look up the meaning of "remount" to the U.S. Army, the name Remount Road in North Little Rock will suddenly make sense.)

Maj. Richard B. Wainwright, Capt. S.O. Garrett and First Lt. Percy C. Fleming attended a dance Saturday night at the Country Club of Little Rock — which stood where it is today. About 2:15 a.m., Cpl. James W. Brett of Camp Pike was driving them and a fourth officer back to Camp when the car rammed through the railing of the viaduct.

At first it was thought the rain obscured the windshield so Brett couldn't see the curve, but later the Democrat reported the windshield was rolled down. It was a new Cadillac, and windshield wipers existed. But according to the profile of their inventor Mary Anderson at invent.org, Cadillac didn't adopt wipers as standard equipment until 1922.

The big car plunged from the viaduct to the railroad tracks below. Engineer Frank Snyder saw it come down in time to stop his switch engine just feet away.

Bill Harris, watchman at the south end of the Baring Cross Bridge, saw the hulk illuminated through the rain by the engine's headlight. He called for ambulances, which came from the funeral homes of Healy & Roth and Ruebel & Co. because undertakers provided community ambulance service — hearses being the right size to hold stretchers.

BAD INFRASTRUCTURE

Meanwhile, across town, a stormwater river roared along Third Street between Main and Louisiana streets and flooded Second Street east and west from Main. As the Gazette observed May 17:

The water was up over the sidewalks. It backed up into the Gazette pressroom, entered the Gem theater on Third street and seeped into the Leader Company store and other store buildings between Second and Third on Main street.

Summoned from his bed to view the scene at 2:30 a.m., street commissioner Florance J. Donahue said it looked "very bad." Later in the morning, the damage was found to have been not so bad, but the streets were torn up.

An editorial in the Democrat celebrated this "blessing in disguise":

It carried off substantial sections of Main street's wood block pavement. That, it seems, is the only way we will get rid of it. When there is nothing left to patch we will quit patching.

Unfortunately, no, Donahue said: The streets could be repaired with blocks stored under the auditorium at City Hall.

The glut of stormwater was delayed on its way toward the Arkansas River, the Gazette explained, because the wall around the Town Branch had collapsed the month before at Second and Rock streets. That debris had not been removed, and it blocked most of the water draining off the streets.

At the risk of boring our patient historians, Old News will now try to explain about the Town Branch.

Once, this was just a seasonal creek that made a ditch. As William B. Worthen described it for The Arkansas Historical Quarterly in 1987, "When the grid of the city of Little Rock overlaid the natural terrain, the drainage ditch, fed by smaller branches, cut diagonally across from Holly (Eighth Street) and West Main (Broadway) to Mulberry (Third) and East Main (Main), and flowed north on Main to Cherry (Second) and east on Cherry to the Quapaw line."

It crossed a city block between Commerce and Sherman streets and continued down Third past Collins Street, turning south into lower elevations then east of town.

Early in the city's development, it was helpful, carrying away waste, providing irrigation, serving as a skating rink in winter. But as the city grew, Worthen explains, the Town Branch was a menace, an open sewer that flooded.

It was useful in providing metaphors about local politics: Worthen writes that it became a symbol for rottenness. In 1849 one social critic complained that gamblers and dram sellers were so wicked they "rolled themselves in that sweetscented receptacle of filth.”

Over the decades, parts were encased in concrete and channeled, but with a crazy quilt of methods.

As late as 1924, sanitary sewer lines emptied into the ditch.

In 1920, in the days after the storm, an Army delegation met with Mayor Ben Brickhouse to insist something be done about the Lincoln Avenue Viaduct. As one witness had complained to the Democrat, it was a "death trap." Two years before, under similar conditions, another soldier and his sweetheart had died there. This time, the Missouri Pacific railroad agreed to paint the railing white with diagonal stripes and to place timbers along the inside rails at a height just above that of auto axles. A spotlight on the bridge would be repositioned.

That viaduct was replaced in 1928 after the Great Flood of 1927. (See photos of the Lincoln Avenue Viaduct at arkansasonline.com/518bridge.)

Also after that great flood, the last open section of the Town Branch was dealt with. As Worthen writes, "The meandering stream, cut off, confined, and polluted, was replaced in concrete; the Town Branch, now a mere storm sewer, could no longer threaten the property, health, or safety of Little Rock citizens."

So you see what can happen? Great disasters can inspire big improvements.

Email:

cstorey@adgnewsroom.com

Style on 05/18/2020