HACKENSACK, N.J. — A Rutgers University ocean lab has two remote-controlled gliders, or small robotic submarines, in the Gulf of Mexico helping federal agencies predict the path of the oil plume from the BP ongoing spill.

Shortly after an explosion triggered the spill in April, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration turned to ocean experts at Rutgers’ Coastal Ocean Observation Lab. The lab sent down two research gliders with sensors to collect ocean data in the Gulf. They remain deployed off Tampa, Fla.

The Rutgers team has also taken the lead role in consolidating all the data coming in from a small fleet of other research equipment scattered through the Gulf. Having all the information sent to the Rutgers lab in New Brunswick, N.J., has enabled scientists from NOAA and other government agencies to get a more complete picture of the oil spill - and its possible path.

“This is what we do, and so when we heard about the disaster, we knew this was how we could contribute,” said Josh Kohut, a Rutgers oceanographer associated with the lab.

So far, the gliders have sent updates about the flow of ocean currents as well as water temperature and salinity readings, which researchers are using to create models that predict where the oil spill might go.

The gliders are also reading the colors of fluorescent light in the water, which can be produced by aquatic life and other organic material, including oil. Several gliders stationed along the Louisiana and Mississippi coast near the spill have detected certain fluorescent bands that are distinctly different and that researchers suspect are produced by the oil. They are awaiting confirmation from signals from shipboard sensors.

The Rutgers gliders off Tampa, which is far south of coastal areas where the oil has come ashore thus far, have not yet detected this kind of fluorescence. Instead, they have so far recorded the fluorescent bands that scientists say are consistent with the region.

The lab has used gliders for a decade to measure the speed, salinity and water temperature of the ocean currents off New Jersey. Last year, the Rutgers team became the first to successfully send one of the remote-controlled gliders clear across the Atlantic, from New Jersey to Spain.

change oceanography and provides a wealth of new information on the ocean with a wide array of applications that can help at-sea rescues, the fishing industry and, now, federal officials monitoring the BP oil spill.

The gliders - which look like small yellow torpedoes - are made from plastic and aluminum, measure 6 feet long and weigh about 100 pounds. They can operate for more than a month on a bundle of alkaline batteries and use a little more than a watt of power at a time - equivalent to three or four Christmas tree lights, said David Aragon, a research staff member.

They send data back to the lab by satellite phone in their tail fins.

The gliders move slowly - no more than a half-mile per hour - and because they have no propellers, they can’t move in a straight line. They follow a roller-coaster path. The glider’s nose captures water, which helps push the robot forward and down, and then spits the water out, sending the robot back up toward the surface, said Scott Glenn, a Rutgers oceanographer and a co-founder of the Coastal Ocean Observation Lab.

Researchers can switch out different sensors in a glider’s payload depending on what kind of data they’re seeking.

In addition to Rutgers’ two gliders, the team in New Brunswick is consolidating data from gliders in the Gulf owned by the University of Delaware, the University of Washington and the University of South Florida.

Federal officials are able to obtain information on ocean movement from orbiting satellites that can read deeper water currents and from shore-based radar that can measure shoreline ocean movement. The gliders are helping them gather information in a zone that neither the satellites nor the radar can read.

Much of the spill cleanup has been focused on the oil on the Gulf’s surface. But some researchers have detected possible plumes of oil weaving through the Gulf far below the water surface.

“Whether an underwater plume of oil really exists is still being debated,” Glenn said.

In the Gulf, the gliders have faced some problems, chiefly groups of remora, also called suckerfish. They normally hitch free rides on sea turtles, sharks or other larger fish, but apparently have taken a liking to the gliders, Glenn said. As the fish latch on, they prevent the robots from ascending to the surface.

Rutgers owns 20 gliders, which cost $70,000 to $100,000 each. Its gliders have been used off the coasts of New Jersey, Puerto Rico, Hawaii and Australia and in the Mediterranean Sea. Researchers are starting to use the robots in heavy weather to better understand the impact of storms on currents.

“They don’t get seasick,” Glenn said of the gliders.

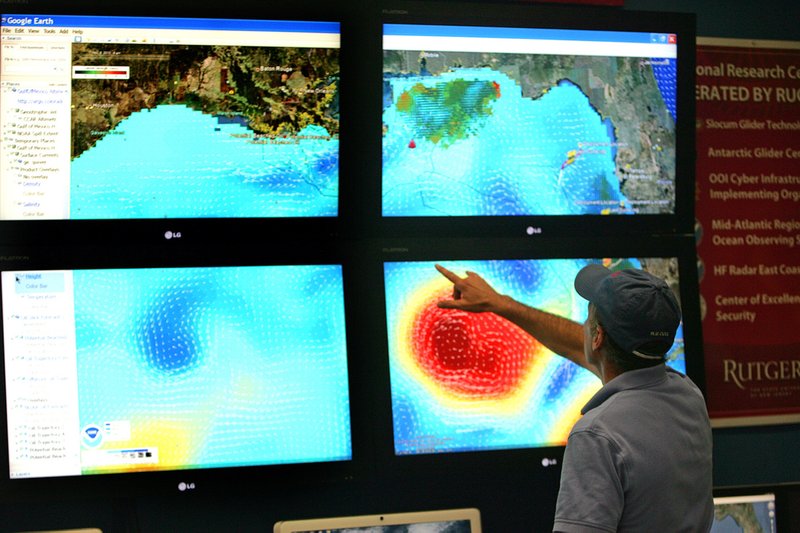

The lab’s main data collection room looks like a miniature NASA launch control center. Large color monitors cover one wall, and these days show updated color-coded images of the Gulf of Mexico, with warm areas shaded dark orange and cooler areas depicted in greens and blues. Hundreds of thin white arrows on the screens show the direction of Gulf currents.

Business, Pages 19 on 06/28/2010