LONDON — Britain headed into the weekend Friday without a new leader as the Conservative Party’s David Cameron scrambled to fashion a working government after voters produced the nation’s most divided Parliament in decades.

Final results from Thursday’s election showed Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s Labor Party suffering its worst defeat in 80 years. But Conservative gains fell short of a clear majority, setting up a hung Parliament - in which no party has overall control - after 13 years of Labor rule.

Cameron and Brown were openly courting coalition deals with Nick Clegg of the third-place Liberal Democrats. In a blow to Brown - the prime minister since 2007 - Clegg signaled his intention to negotiate with the Conservatives first.

“I think it is now for the Conservative Party to prove that it is capable of seeking to govern in the national interest,” Clegg said.

Brown, meanwhile, dangled before the Liberal Democrats their dream of major electoral change.

Ideologically, the center-left Clegg has more in common with Brown. Both oppose the immediate cuts Cameron has said are needed to begin rebalancing Britain’s debt-burdened economy, and both have attacked his Tories as the party of privilege.Clegg also has clashed with Brown and Cameron over Britain’s expensive submarine-launched nuclear deterrent, which the Liberal Democrat leader has indicated he may want to scrap.

Cameron, 43, said “we have to accept that we fell short of an overall majority” as results showed his party had won 306 of the 650 seats in the House of Commons, less than the 326 needed for outright victory.

Labor won 258 seats, the Liberal Democrats 57, and smaller parties 28. Voting in one constituency was postponed until later this month because of the death of a candidate.

“Britain needs strong, stable, decisive government and it is in the national interest that we get that on a secure basis. ... I want to make a big, open and comprehensive offer to the Liberal Democrats,” Cameron said.

He said he would not bend to the Liberal Democrats’ proposals to rethink Britain’s nuclear deterrent, grant a partial amnesty to illegal aliens or pursue deeper integration with the European Union. But he acknowledged that the two parties shared some ideas, including views on the economy and education.

But Cameron promised only a “committee of inquiry” to look into the Liberal Democrats’ major goal: a change of Britain’s electoral system so that the number of seats gained is based on the percentage of vote a party achieves. They’ve said that is fairer than the current system, in which a party can win a parliamentary majority by getting only a third of the votes.

Some Conservatives suggested the party would be willing to sweeten the deal in other ways, such as offering cabinet posts.

“The important thing is to tackle the problems we have with the economy. They are very serious,” John Major, the last Conservative prime minister and a party elder, told the BBC on Friday. Major, who lost to Tony Blair in 1997, added, “If the price for that is one or two liberals in the Cabinet, it’s a price in the national interest that I personally would be prepared to bear.”

Cameron also left open the option of trying to form a minority government if the Liberal Democrats turned him down.

Brown also appealed to the Liberal Democrats to make a deal and went further than Cameron by promising quick legislation on electoral changes.

“There needs to be immediate legislation on this to begin to restore the public’s trust in politics,” Brown said.

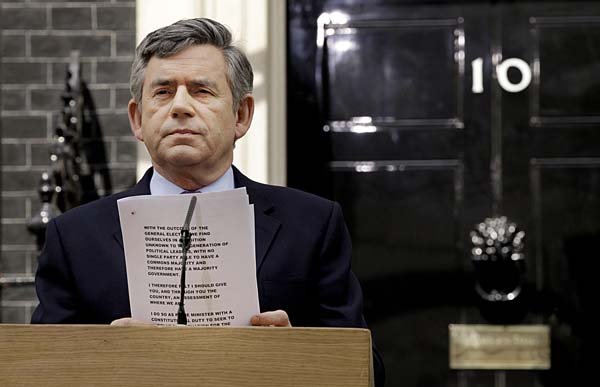

“The question for all the political parties now is whether a parliamentary majority can be established that reflects what you, the electorate, have told us,” Brown said in a statement delivered outside 10 Downing St.

Even a deal with the Liberal Democrats would leave Labor a few seats short of a majority, meaning the party would have to turn to Scottish and Welsh nationalists for further support.

“I have a feeling Gordon Brown will have to be dragged from No. 10 with his fingernails in the door posts,” said Victoria Honeyman, a lecturer in politics at the University of Leeds.

Thursday’s closely fought election was the first since 1974 to produce a hung Parliament. As the pound and the FTSE-100 index fell sharply, pressure mounted for a quick solution.

“It’s vital that this political vacuum is filled as quickly as possible,” said Miles Templeman, director general of business group the Institute of Directors. “The country simply can’t afford an extended period of political horse-trading which delays much-needed action to tackle the deficit.”

Cameron and Clegg held telephone talks Friday. Clegg was later seen leaving his party’s headquarters near Parliament, while senior Conservative lawmaker William Hague and George Osborne, another senior Tory figure, were both seen leaving a meeting at the Cabinet office.

All declined to comment on the prospects of any potential deal.

Although Britain has no written constitution, senior civil servants have been careful to lay out the rules in the event of a hung Parliament.

Mandarins from the prime minister’s office, the civil service and Buckingham Palace will make sure all parties are kept informed as politicians meet and wrangle. Queen Elizabeth II, as head of state,will ultimately have the job of inviting someone to become the new prime minister, but she plays no role in deciding who that will be.

The parties hope to make a deal before the financial markets reopen Monday, but talks could drag on until May 25, the date set for the queen to read out the new government’s plans for the coming term of Parliament.

Turnout for the election, the closest-fought in a generation, was 65.2 percent, higher than the 61 percent in Britain’s 2005 election.

Some polling stations were overwhelmed by those interested in casting ballots, and anger flared as hundreds of people were blocked from voting when polls closed.

Eric Shaw, lecturer in politics at Stirling University in Scotland, likened the election to “a game of poker in which everyone has been dealt a rather poor hand.”

“There is a possibility that the player with the best hand wins, but there is a second possibility that the player who wins is the one who holds their nerve,” he said.

The governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, was widely quoted recently as saying that whichever party came into power now risked being voted out for a generation at the next election because of the unpopular decisions it would have to make.

But Tony Travers, a political scientist at the London School of Economics, said a bitter pill for the public did not automatically have to be a deadly one for the government.

“The public in Britain knows rather more than the politicians have been willing to tell it, that the deficit has to be reduced,” he said. “The question is ... how they manage it, how they explain what they’re doing, how they protect the vulnerable, how they spread the burden. If they can make it appear relatively fair, then they’ll be credited for it. No one’s going to blame them for the initial crisis.”

Tim Montgomerie, who runs the grass-roots website Conservative Home, said many activists would be disappointed with the campaign by Cameron, who staked his leadership on returning the Conservatives to power after 13 years.

“As he enters his talks with Nick Clegg, David Cameron has got to realize that he’s not just building a coalition outside the party; he’s got to build a coalition inside the party, too,” Montgomerie said.

Clegg’s party failed to capitalize on his TV debate performances and midelection polls showing him rivaling Labor for second place. The party ended up with five fewer seats than before the election.

“Many, many people during the election campaign were excited about the prospect of doing something different,” Clegg said. “But it seems that when they came to vote, many of them in the end decided to stick with what they knew best. And at a time of great economic uncertainty, I totally understand those feelings.” Information for this article was contributed by Jill Lawless, Danica Kirka, David Stringer, Paisley Dodds, Raphael G. Satter, Robert Barr and Jennifer Quinn of The Associated Press; by Anthony Faiola and Dan Balz of The Washington Post; by Robert Hutton, Kitty Donaldson, Thomas Penny, Mark Deen, Scott Hamilton, Gonzalo Vina and Rodney Jefferson of Bloomberg News; and by Henry Chu of the Los Angeles Times.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 05/08/2010