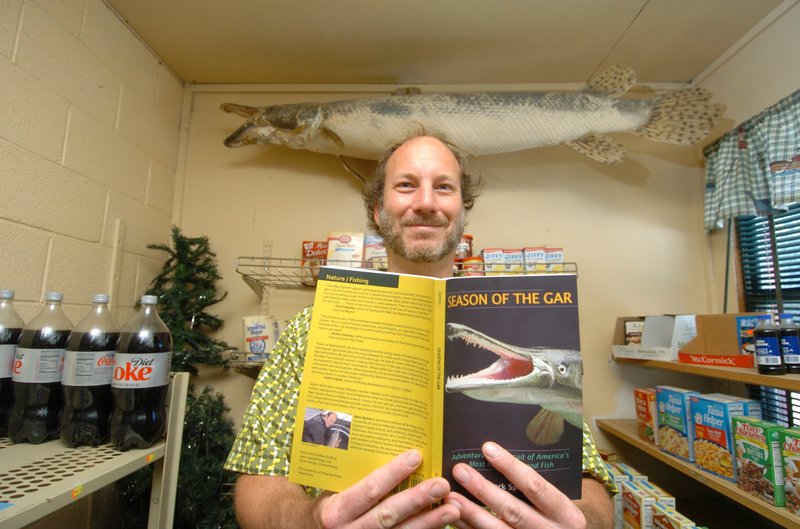

CONWAY — Mark Spitzer is a novelist, a poet, a book translator, an editor of a prestigious literary journal, a professor, and, as he puts it, a “lifelong, passionate fisherman” on a mission to defend and protect the much-maligned gar.

“I’m just a creative writer with an interest in fish - well, maybe an obsession,” said Spitzer, a former writer-in-residence at the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris.

Spitzer, who teaches writing at the University of Central Arkansas, became interested in the homely fish as a boy when he read about them. He began gar fishing when he moved to Louisiana in 1997.

“They’re just this fantastic, crazy, monster-looking fish that inspire the imagination,” he said.

But the creatures do not inspire everyone.

“People hate gars. Gars have been equated with demons and devils for centuries on this continent,” Spitzer said.

“There’s been a lot of misinformation spread about them - that they attack humans, that their flesh is no good to eat, that they should be destroyed because they eat all the other fish. All this is false.

“But generation after generation of fishermen in the South have persecuted gar because of faulty science and state agencies that [in the past] have encouraged the killing of them.”

Spitzer, managing editor of Exquisite Corpse, began researching the gar in 2001 through fishing trips in Louisiana, Missouri and Texas. In 2005, he started a book, the recently published Season of the Gar: Adventures in Pursuit of America’s Most Misunderstood Fish.

Spitzer’s credentials also include a television appearance on an episode of the Animal Planet program River Monsters.

Over the years, his studies have examined “the folklore of alligator gar, the history of them ... the science, depictions [of them] in art and literature,” as well as the sociology and psychology surrounding the fish.

The gar species has five different fish. Spotted gar is the most common in Arkansas. The largest is the alligator gar, which can reach up to 10 feet long and weigh hundreds of pounds if it lives more than 40 years, Spitzer said.

“They [alligator gars] can live 60 to 100 years, basically,” he said.

The species’s image isn’t helped by its members’ alligator heads, fangs and armored bodies - scales made of the bone-like substance dentin.

Alligator gars are “very prehistoric,” said Spitzer, who has a 2-foot-long short-nosed gar mounted in his Conway home. “They were here before the dinosaurs.”

Spitzer said Arkansas has some alligator gars but not many. “We’re trying to bring the population back,” he said.

Despite lingering myths, gars don’t eat game fish, Spitzer said. Rather, they help rid rivers of invasive and destructive fish such as carp. “So they help balance out the ecosystem,” he said.

Further, alligator gars do not regularly attack humans, despite stories to the contrary, Spitzer said.

“They’re happy like dolphins,” Spitzer said. “That is just false. ... In fact, I have swum with them. ... They’re just big, gentle creatures.”

Alligator gars have a delicate reproduction system and are highly threatened. Because of an increasing number of dams and levees, the United States has fewer flooded areas where the fish can reproduce well, the professor said.

“We only know of about 200 alligator gars in the state, and there used to be tens of thousands” in the 1920s, he said. Even so, the fish are not on anyone’s endangered lists because, he said, most people don’t care about them.

Unlike alligator gars, smaller gars don’t have any trouble reproducing, Spitzer said.

State agencies realize that they were wrong in the past about alligator gars and are looking at management plans to preserve and propagate them, Spitzer said. But he believes that changing the minds of many fishermen will be a slow process.

“What we’re trying to do in Arkansas is recover their habitats ... where they can reproduce,” he said. “Then we can start stocking them.”

Lee Holt, fisheries management biologist with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, said he and other biologists are working on the Arkansas management plan.

The first job, Holt said, is to find out where the fish are, how many there are and assess their potentially available habitat.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Holt said, the White River had so many alligator gars that tourists would come from as far awayas Wisconsin and pay $200 or $300 to go on guided tours and fish for them.

Holt said the first goal is to increase alligator gar numbers because the fish serve an environmental purpose. But, he said, “I don’t know if we’ll ever get them back to where they once were.”

Holt also would like to “revive a unique sport fishery in the state.”

Spawning habitat is just one reason the number of alligator gars has declined, Holt said. “I don’t think that anybody will be able to pinpoint one specific thing that has led to the lower populations. I think it’s going to be a number of things.”

As for Spitzer, he also enjoys cooking some of the smaller, more bountiful gar fish.

He makes one dish called gar balls, “a translation of a French recipe called gar boulettes” consisting of cornmeal, parsley “and all sorts of ingredients” to create fish “meatballs.”

But Spitzer doesn’t eat alligator gars because “they’re too rare.”

Besides, he said, “The smaller ones are definitely better. The bigger they are, the more pollutants they have in them.”

Arkansas, Pages 9 on 05/17/2010