ARKANSAS — Like many Arkansans, my friend Lewis Peeler of Vanndale spent time in his yard recently removing storm-damaged trees. That was unpleasant enough, but just hours after sawing up several trees, a terrible rash developed on both his arms. Soon he had little fluid-filled blisters on his hands and fingers, too.

“I’m covered with poison-ivy rash, and the itching is horrible,” he told me later. “I know what poison ivy looks like, but I guess I didn’t notice some growing on or around the trees I cleaned up. In the past, I’ve been only mildly allergic to it, but this time I got it really bad.”

I could sympathize. Unlike Lewis, I’ve been highly allergic to poison ivy since childhood. I’ve had that itchy rash on my hands, arms, legs, feet, eyes, toes, ears and nose. It has annoyed me in spots unmentionable. I’ve gotten it while cutting firewood, climbing trees, petting dogs, unlacing my shoes and stalking squirrels; in Arkansas and New Jersey; in the backwoods and in my yard; city and country; summer and winter. Just being near it causes my lower lip to tremble, cold sweat at the temples and a blanched complexion.

Why should a grown man be so fearful of an immobile little shrub? You wouldn’t ask if you ever had a severe allergic reaction to this pesky greenery. Some people go their entire lives without being thus afflicted, but those of us who haven’t been so fortunate fear poison ivy like a plague.

Poison ivy thrives in every county in Arkansas and in almost all states except the driest part of the desert Southwest. The plant thrives on a wide variety of sites and soils, open and wooded, and is as common in flower beds as it is in woodlands.

Were it not so toxic, this relative of the cashew would be an attractive candidate for garden cultivation. The plants are beguilingly attractive, glossy green in spring and adding spectacular crimson and gold foliage to autumn landscapes. Unfortunately, most of us are susceptible to its skin-irritating properties, particularly light-skinned individuals and young people. And even those who have not previously experienced reactions may become more susceptible in later age. Being able to identify poison ivy is thus an important bit of information for every person who spends time outdoors, whether cultivating perennials in the flower garden or hunting deer in remote backcountry.

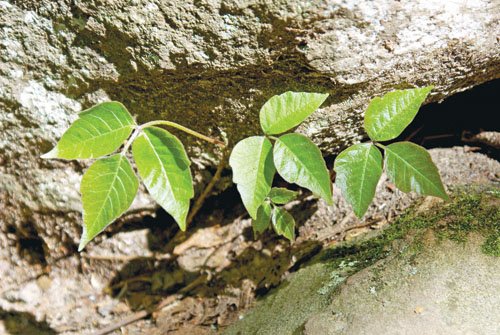

Poison ivy plants have glossy leaflets in groups of three. In late summer or early autumn, clusters of buckshot-sized white “berries” appear on older plants. Years ago, folks came up with a handy jingle to help remember these key identification characteristics: “Leaflets three, let it be; berries white, poisonous sight.”

Individual plants may differ considerably, from long, high-climbing vines growing on trees to individual shrubs or dense, low-growing ground cover. The plants lose all their leaves in winter, a fact making many people more susceptible to exposure during this season when poison ivy is more difficult to identify. Poison oak also grows in Arkansas but is confined to smaller portions of western and central counties. This close relative of poison ivy also has three leaflets and produces similar allergic reactions. Poison sumac does not occur in the state.

All parts of poison ivy — the leaves, twigs, flowers, berries and roots — contain an oil compound called urushiol. This sticky, sap-like substance is extremely virulent and long-lived. Get as little as 1-billionth of a gram on your skin and you might be scratching yourself silly. And urushiol is so stable, it has been proven to remain active on dried plant specimens for over 200 years!

Touching the plant allows the skin to absorb this irritating toxin. If the victim is allergic, the contact point will redden eight to 24 hours after exposure. The skin then develops itchy blisters or bumps. The entire affliction may last more than a week, long enough for the sufferer to think the itching will drive him crazy.

Despite popular misconceptions, scratching the lesions isn’t what spreads the infection. Fluid in the blisters doesn’t contain urushiol. If the oil remains on skin near the blisters, however, it can easily be transferred when scratching.

A person need not actually touch the plants to contract the dermatitis, either. A poison-ivy attack also can occur after handling clothing, pets, sporting equipment, tools or even harvested game animals such as deer or squirrels that have come in contact with the plants.

Serious allergic reactions also can result from burning poison ivy. The vines may be unknowingly burned with firewood or leaves, and urushiol oil adheres to bits of soot and ash in the smoke. Anyone standing in or breathing the smoke is likely to experience a rapid and potentially dangerous allergic response. A person trying to rid the yard of the noxious weeds, chuckling with satisfaction while watching them go up in smoke, may not have the last laugh.

Herbicide sprays are the best means for eliminating the plants. Several companies sell aerosol products for use as poison-ivy killers that are effective if used according to direction. Contact herbicides such as Roundup are not as effective against this pest, and repeat sprays may be required.

Should you touch poison ivy, wash thoroughly with soap and water as soon as possible. Also wash your clothing, pets, camping gear or anything else you suspect of contamination. If you still contract the rash, you can help alleviate the itching with over-the-counter medications such as calamine lotion and Benadryl. More severe reactions may require doctor treatment and prescribed medications such as corticosteroid pills, ointments or shots.

Wearing a long-sleeved shirt, long pants and socks helps a person reduce contact with poison ivy when afield. But the only sure means of preventing an outbreak is learning to recognize the plants and avoid them.

Teach your children how to recognize poison ivy, too. It’s one loving thing an old scratcher can do for a young friend.