LITTLE ROCK — In the preface to her book Bouldering USA, Alli Rainey Wendling suggests rock climbing could be the nation’s antidote to depression.

“I’ve long thought that if more people would just rock climb, the world would be a much happier and healthier place.

“If the population at large could experience joy in movement and exercise instead of viewing working out as a loathsome task ... if people could experience the bliss of complete mental, physical, and emotional unity experienced via a regularly undertaken physical activity like rock climbing, then far fewer people would feel the need to turn to prescription medications to enhance their moods.”

Rainey Wendling isn’t a psychiatrist. She’s not even a scientist. She’s a world class boulderer and climber, and a writer. The first means she knows something about the sport; the second means she knows something about everything - so we writers think.

Rebekah Evans, who has a practice and a doctorate in psychology, said there’s lots of evidence to link exercise with improved moods, that those who maintain active lifestyles have lower rates of anxiety and depression, but that all this is not the same as saying rock climbing will reverse a clinical diagnosis.

FAILURE HINGES ON THE PHALANGES

Rock climbing is very therapeutic. More spiritually palliative, say, than summer softball or water skiing. It narrows the focus like not even running will. Call it our primordial instinct, something we share with reptiles, but when you climb, confronted with a rock face and gravity and falling, holding on and getting higher is all you can think about.

On the other hand, climbing is easy to give up on. As a recreational sport, it’s dissonant and frustrating. Guys and gals who played sports in school are accustomed to taking up a new recreational activity - kickball, cycling, horse shoes - with some reasonable expectation of early success.

Why? Because, well, it’s just never been any other way.

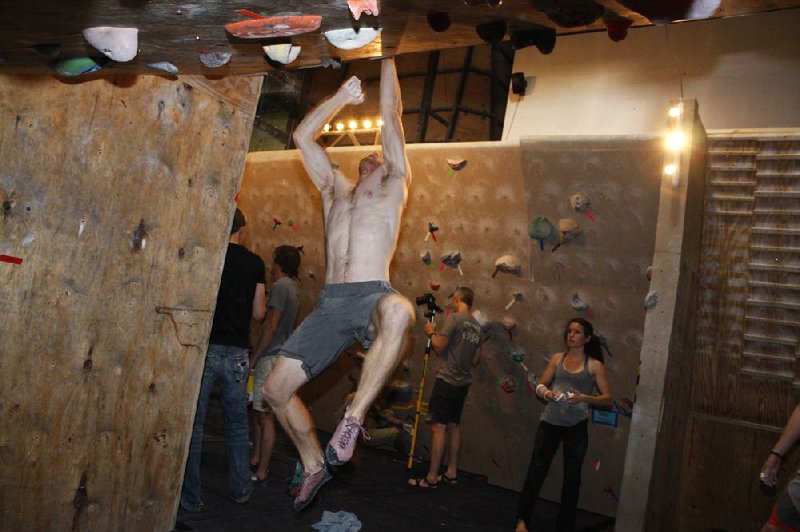

“You see all these guys come in here with these super big muscles and they can’t hold on,” says Tristan Fowler, 29, of Little Rock.

Climbing is fundamentally different. It takes none of the aerobic endurance or hand-eye coordination of most organized sports. It relies on strength sufficient to do a couple pull-ups or four, but beyond that, weight-room bulk is ballast.

I met Fowler two weeks ago at the Little Rock Climbing Center’s summer Boulder League.

Unfairly, Fowler is a spidery climber and saddled with “super big muscles.” He also cycles and weight-trains. Still, he says, at first it astounded him just how much failure hinges on the phalanges.

“Finger strength - you have to deal with the pain of your fingers splitting and still hold on,” he says.

Beginning boulderers will find that the first thing to go is the soft skin on the undersides of your fingers and the second is the muscles and tendons beneath.

Rennie Karnovich is another Boulder Leaguer whose body is visibly muscular. At 42, she says, she must be the oldest one in the league.

“Grip strength. It’s definitely grip strength ... and a lot of time in” the gym.

PRE-EMPTIVE CORRECTION

I can already hear the discord from climbers across the state who take issue with my earlier statement, “it takes none of the aerobic endurance.”

Wait, did I just quote myself? Take the keyboard away.

Fowler says some outdoor climbs are exhausting. They take you on long hikes with gear that would make a yak slack, and when you get there, the climbing might go on just as long. It’s “ full-body exhaustion” that makes cycling for four hours feel cozy.

“And that’s where the mental comes in. That’s why it’s more exciting for me than cycling.”

ActiveStyle, Pages 23 on 07/23/2012