In the 1950s when Randy Duncan was born in New Orleans, comic books were denigrated by educators as the reading material of misdirected children and slackers, who were being led by the colorful pages down the road to ruin.

In those days, some groups even held bonfires where they burned comic books to emphasize how the popular stores were the lowest form of literature.

However, things were changing by 1966, when 8-year-old Duncan began to read comic books. The writers were developing characters that carried the problems and angst recognized by their young readers. In time, the superheroes reflected the social concerns of the 1960s. Those costumed characters were transformed to become icons of popular culture, at the center of a multibillion-dollar industry of not only comic books, but graphic novels, movies and merchandising.

Such a movement is worthy of scholarly study, and Duncan was one of the pioneers of that study.

“I remember seeing comic books with their covers gone for 5 cents,” Duncan said. “I remember reading the Legion of Super-Heroes, and I was thinking, ‘I get these guys.’ Later I learned that title was being written [at that time] by a 13-year-old.”

First attracted to the drama, depicted in bright color on the comics’ pages, Duncan said, he began to notice some of the magazines were more visually interesting than others.

Like many of his generation, his passion for comic books continued into college, where he earned a liberal arts degree.

“Parents want to you plan on doing something respectable, so my cover story was that I was going to law school,” he said. “I liked the debate team, and there was an appeal to arguing a case, but it was never part of my real plan.”

As a graduate student, he realized he was headed for a career as an English teacher, something he didn’t want to do. Transferring to Louisiana State University, he studied communications.

“I was in a film class at the same time Frank Miller was drawing the Daredevil comic book,” Duncan said. “I thought Miller was doing things with the story panels in the comics that were like cinema techniques, like the Expressionist filmmakers, and I did a paper on that.”

Duncan’s professor liked the paper and suggested that the subject might make a good doctoral dissertation.

“LSU was bold enough to let me do a paper with comics,” Duncan said. “I am not sure I could have had a subject like that accepted in the 1980s at many schools.”

The result was Panel Analysis: The Rhetoric of Comic Book Form, and Duncan had found a subject on which he could build a career. Next, he had to get a job.

“There were no comic scholars at the time, but I had strategically placed ‘Rhetoric’ in the title, so it sounded academic,” Duncan said.

He found a position at the University of Vermont but resigned in the first week, agreeing to work out the year. Next he accepted a teaching job at a college in Birmingham, Ala., but he received a call that the position was not included in the budget.

In the meantime, on a trip to the seashore in Maine, Duncan failed to notice that the tide had come in, cutting off from the shore the rocks where he had spent the day taking photographs.

“I walked back to the beach, but the water got higher with each wave, and it was touch and go,” he said.

The trip also gave him pneumonia, and Duncan said he was shaking with fever when he interviewed for a teaching position at Henderson State in 1987.

“I was told that some of them thought I might be an alcoholic, I was shaking so, but they hired me anyway,” he said. “I thought I would take the job for a year or two, but I have now been here 25 1/2 years.”

In Arkadelphia, Duncan continued his work with comics because he remained a loyal reader.

Comic book readers establish a parasocial relationship with the characters, Duncan said.

“It is the same reason people watch soap operas every day,” he said. “We care about the characters and have for more than half a century. I admit I care more about Peter Parker (Spider-Man) than I do about my cousins. Boy, I hope none of them reads this.”

Duncan looks at how comic book artists use their art to tell the story, what he calls the language of comics.

“I try to help students develop their own vocabulary to describe what happens in the books,” he said. “First, there is external-image functional analysis.”

He said there are three ways the artists tell their stories. First is to show the world of the characters.

“You see the world they see,” he said. “Then [the second way] there are the perceptions of surprise and fear that the artists project on the characters.”

The third way a story is told by the artist actually comes from biblical studies.

“Hermeneutic images require the reader to interpret the images, and you are prompted by the author,” Duncan said. “Nothing on the page is an accident, and to understand, you need to think about and engage with the author and what you know about the character. Even if you have your own ideas about what is happening, it is that moment of engagement that is important.”

That is the key to his comic book studies and a high mark of Duncan’s classes, he said.

“In a broad sense, all of my classes are about how humans use symbols to create meaning for other humans,” he said. “I discovered that my best teaching occurs not when I tell them, ‘This is how it is,’ but when I create situations and challenges that get my students excited about developing their own perspectives.”

Duncan said he hopes his students will become astute communicators who are not easy to manipulate, but “who can use communication to impact their world.”

His students take classes such as comics as communications, strategic digital media and rhetorical theory. He also has a seminar in which his students create their own graphic novels.

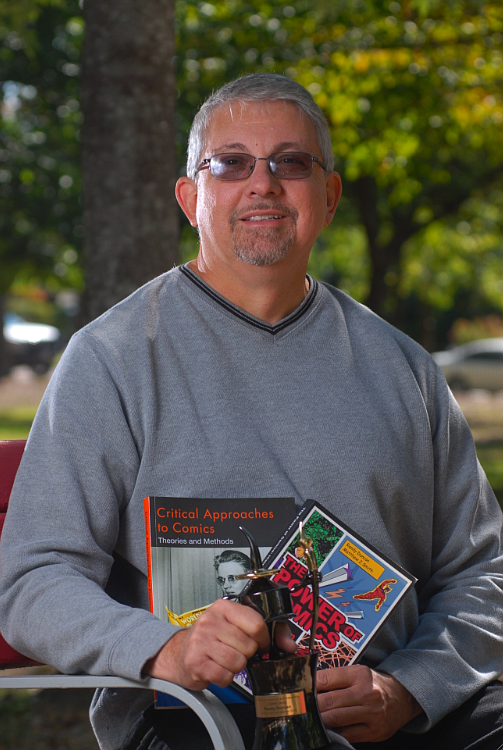

Instead of being a maverick of literature studies, Duncan is now considered a pioneer in a major field of communications analysis and criticism. Early this year, Duncan was presented with the Inkpot Award for Achievement in Comic Art during the Comic-Con International in San Diego, the largest popular culture convention in the world.

The award is given to those who have made major contributions to the popular arts. Last year, the award when to Steven Spielberg, and it has also been awarded to others, such as the creators of Batman and Superman.

On Nov. 8, Duncan will be honored as the 2012 Arkansas Teacher of the Year in the college/university category by the Arkansas Council for Teachers of English Language Arts.

The Power of Comics: History, Form & Culture, a textbook for teaching how and why comics books are part of American literature, has be written by Duncan and Matthew Smith, a professor and chair of the communications department of Wittenberg University in Ohio. In an introduction to the book, Paul Levitz, president of D.C. Comics, said Duncan was one of the first to give comic books the critical look they deserve.

Thomas Inge, a professor of humanities at Randolph-Macon College in Virginia, called Duncan one of the “brightest and best of international comics critics.”

Even after 25 years at Henderson, Duncan said, he is not interested in retiring and has never really considered leaving the university.

“It is a wonderful place to work,” he said. “It really is the school with a heart. I have often been told by visitors that professors care about the students here, and I know the students are emotionally engaged with the school.

“I am able to teach about comic books, and there is a special collection of graphic novels in the library, and there are others on campus who understand comics are worth studying. Why go anywhere?”

Besides, he said, Superman was just rebooted, and a whole new crew of X-Men may be coming on board.

Staff writer Wayne Bryan can be reached at (501) 244-4460 or wbryan@arkansasonline.com.