German prisoners of war got to sit up front for a Lena Horne performance at North Little Rock’s Camp Robinson, while the base’s black American troops were relegated to the rear of the hall.

The Germans were the conquered enemy, but they were still privileged in Jim Crow Arkansas by the color of their skin. That’s the way it was during the 1944 Christmas season in a state that housed some 25,000 of the 350,000 German captives shipped to the United States after Allied triumphs in North Africa, Italy and France.

And that evidently was too much for Horne, then one of America’s most celebrated black performers.

According to her 1965 autobiography, she said, “I don’t think I have ever been more furious in my life. I marched down off that platform and turned my back on the POWs and sang a few songs to the Negro guys in the back of the hall. But by the third or fourth song, I was too choked up with anger and humiliation to go on.”

That World War II incident stands as a revealing moment in the dimly remembered history of the troops from Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich around the state.

Much has been reported and written about the 16,000 Japanese-Americans interned during the war at Arkansas camps in Rohwer and Jerome. A museum depicting those controversial detentions opened last month in McGehee.

But most Arkansans know little or nothing about the more numerous Germans (and about 4,000 Italians at a site outside Monticello) confined in the state under relatively comfortable conditions as the war in Europe proceeded to Allied victory 68 years ago this month.

There’s scant mention of race relations in the scattered written accounts about those captured members of Hitler’s war machine held at the three main Arkansas camps-Robinson, Chaffee and Dermott (previously the Jerome site for Japanese-Americans). There were also some 30 sub-camps that housed enlisted men assigned mainly to farm and timber work.

In retrospect, however, the state’s POW story holds a measure of ironic juxtaposition. The Germans, after all, were defeated members of a self-proclaimed Master Race. The Nazis condemned Jews and Slavs as untermenschen and systematically murdered millions of them across Eastern Europe.

Shipped across the Atlantic Ocean mainly because there was no room to keep them in Britain, the Axis soldiers found themselves treated with ample decency by their American captors.

That fairness came partly from U.S. adherence to the Third Geneva Convention protecting prisoners of war, but also because they were fellow whites. Skin color truly mattered back then, and white racial supremacy was taken for granted in the states of the former Confederacy. Blacks needed to wear no Star of David because their hue gave them away.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that the German POWs (and the Italians) also got a more positive reception and better treatment in Arkansas than the interned Japanese-Americans, even though the latter were virtually all loyal U.S. citizens.

This difference, wrote Arkansas State University historian C. Calvin Smith in the Arkansas Historical Quarterly in 1994, “can be traced to the fact that many white Arkansans shared the German views on racial supremacy and saw them as racial equals who had been forced into an unfortunate confrontation with the United States. By contrast, the Japanese-American internees were not only viewed as supporters of an enemy nation which was challenging white racial supremacy, but as a threat to white racial supremacy in Arkansas.”

The Geneva Convention specified that captive soldiers should be housed, fed, clothed and medically cared for in much the same manner as troops of the nation that held them prisoner. The U.S. War Department adhered carefully to the Geneva terms with what it called “strict but correct” treatment of the POWs.

“As a result, life in the Arkansas camps was not particularly unpleasant,” wrote historian William L. Shea in a 1978 article co-authored with University of Arkansas at Monticello colleague Merrill R. Pritchett for the Arkansas Historical Quarterly. “The prisoners experienced numerous restrictions, of course … but they generally were well cared for and enjoyed a good deal of free time.”

Still a professor on the Monticello campus, Shea thinks the POWs “were about as comfortable as they would have been in any barracks-type environment in Germany.” They were surely better off than their millions of Wehrmacht colleagues who continued fighting to the death in horrendous combat against mightier Russian, American and British forces in Europe.

TALE OF GOOD TREATMENT

In a memoir edited by Shea in 1985 for the Arkansas Historical Quarterly, former POW Edwin Pelz described his amazed delight at “the friendly acts and humane treatment” of U.S. guards and civilians after his contingent of captives disembarked in Massachusetts. They traveled by train to a camp outside Memphis where he was based for work that included picking cotton in the Arkansas Delta.

Their train ride was “a wonder. We were expecting boxcars, the way German soldiers normally traveled in Europe. Believe it or not, our prisoner-of-war train consisted of Pullman cars with black waiters serving our meals!”

At the Memphis camp, the food “was the same as eaten by American soldiers and seemed to us to be the best in the world. We didn’t have such food as soldiers in the German army. For example, as prisoners of war we had real coffee for breakfast, not ersatz coffee as in Europe. We had fruit with our meals, including pineapple, which was new to me. We feasted on turkey for Thanksgiving and goose for Christmas.”

For their work off-base, prisoners were paid 80 cents a day in scrip good only at the camp canteen, where Pelz noted that “a pack of cigarettes was 13 cents, a bottle of Goldcrest beer was 10 cents.” Yes, beer for the captured enemy-a treat that might bring to mind the old TV sitcom Hogan’s Heroes.

From his days working in northeastern Arkansas, Pelz remembered “how we were treated in a kindly and Christian manner. Unless a person has experienced what we did, it is difficult to appreciate what a sandwich, a smile or an encouraging word really can mean.”

There were not many escape attempts from the Arkansas camps, unsurprising given the comfortable conditions and the fact that the nearest U.S. border was hundreds of miles away. One POW did hike from Chaffee to Fort Smith, as he told authorities, “just to see the pretty girls.”

Another escapee from Chaffee, according to Arnold Krammer’s book Nazi Prisoners of War in America, “remained at large for several days in nearby Charleston despite the fact that he continued to walk around in his prison garb with the letters ‘PW’ stenciled across his legs, seat and back in bright yellow paint.”

The German “finally found himself in a Catholic church where he was recognized as an escapee by a woman in his pew. The priest, when informed, confronted the man, Michael Huebinger, who readily admitted his identity. ‘Then it’s your duty to return,’ the priest said. Huebinger went home with one of his ‘captors,’ drank a cup of coffee and was then driven back to camp.”

There was a German prisoner fatally shot by a guard while trying to escape from the Dermott camp. And one POW beat another to death at Chaffee for allegedly being a “traitor” to the Nazi cause. That killer’s death sentence was commuted to a prison term after the war by President Harry Truman.

Nazi-inspired work strikes occasionally disrupted camp life. In a disciplinary incident reported in Judith M. Gansberg’s 1977 book Stalag U.S.A., an American officer at Chaffee ordered the bayoneting of two POWs who refused to do work “beneath their honor.” The bayoneting “(in the seat of the pants) spurred the men back to work.” RINGS FOR PRISONERS

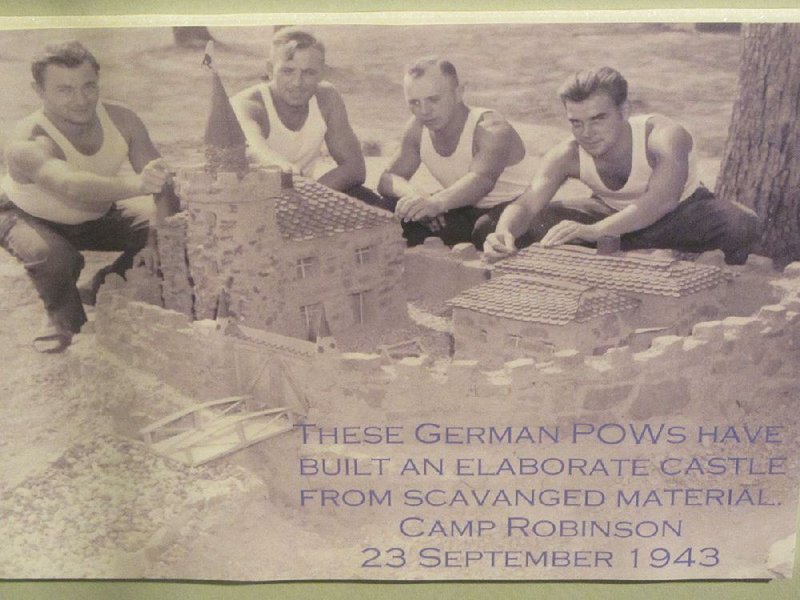

A display at Camp Robinson’s Arkansas National Guard Museum includes a POW ring, explaining that “German prisoners of war were allowed to purchase these ‘class’ rings from traveling salesmen who visited camps around the country”-evoking high school more than a wartime prison.

As the 1978 article by Shea and Pritchett points out, the POWs were a valuable source of wartime manpower for Arkansas farmers, even though the Germans hated chopping and picking cotton. Through the crop-saving agricultural work, they paid back for some of their good treatment.

It took a year after the German surrender before most prisoners were shipped back across the Atlantic. Letters sent after the war by POWs from war-ravaged Germany to Ashley County farmer E.D. Gregory suggest the positive impressions made by Arkansas.

Gustav Menke wrote from Hannover that he hoped to emigrate to the United States, as an unknown number of ex-POWs actually did.

Gerhard Schnause from Leverkusen-Schlebusch wrote: “My imagination very often goes back to those lucky times when we were working for you.”

Rolf Thienemann wrote from Karlsruhe, “Sometimes I wish I’m back in Dermott, to drive every morning with the old Ford bus.”

While the POWs owed their favorable treatment in part to the color of their skin, historian Shea says the few German references to the Jim Crow segregation they witnessed in Arkansas “suggest they thought it was ridiculous.” That ranks as an incongruous point of view for members of a self-proclaimed Master Race.

Many white Arkansans evidently saw the foreign POWs as brethren in a way they didn’t see their black or Japanese-American fellow citizens.

“You know, they’re just like you and I,” Lake City farmer Bob Ridge, who’d employed German POWs, told a Jonesboro television interviewer in 2006. “They’re good people, and I got thinking about it one day, and I said, ‘They can’t help old Hitler’s doing.’ That’s why they’re over here.”

Perspective, Pages 75 on 05/12/2013