Long before he was a six-time Pro Bowler and Super Bowl champion, well before he entered the College Football Hall of Fame, and even before he grabbed Parade All-American honors as a tight end at Parkview High School, Keith Jackson dreamt of being a Central High Tiger.

Jackson lived for some of his 1970s childhood in south Little Rock near Roosevelt Road. He and his friends loved walking the nearly two-mile stretch to Central’s Quigley Stadium to sneak into games. They all expected to play there as Tigers one day.

Jackson’s favorite game was the annual “Bell Bowl,” the intra-city showdown between Central and Hall High on Thanksgiving Day. Jackson was inspired by the litany of prep stars who played in this massively popular event, including Dickey Nutt, who’d followed in his older brother Houston Nutt’s footsteps as a Central quarterback. Central had regularly fielded some of Arkansas’ most powerful prep teams for decades. It had teams tabbed as national champions in the 1940s and 1950s — and in the 1950s, won six straight state titles. By the late 1970s, Hall and Parkview were regularly winning state titles, too.

When Jackson was in seventh grade, his family moved to John Barrow Road — Parkview High School’s attendance zone. He ended up setting records in Quigley Stadium as a Patriot, not a Tiger, and enjoyed every moment of it. He recalls games against Central that packed the house. “It was just standing room only, cheerleaders, full sideline, pep clubs — you had it all. Parents in the stands … it was like it was a big deal.”

To the chagrin of many, Little Rock School District football is no longer “a big deal.” For almost a decade, many of the district’s football teams have fallen to depths unimaginable even 15 years ago. Last season, the five LRSD high school football teams had a combined 11 wins and 43 losses. Three of those programs — J.A. Fair, Hall and McClellan Magnet High School — won a total of 16 games from 2008 through 2012. Barely more than one win per season, per team. The LRSD’s well of future NFL players — which, along with Jackson, produced the likes of Hall’s Leslie O’Neal and Chris Akins, Fair’s Cedric Cobbs and Chris Harris, and Central’s Derek Russell and Reggie Swinton — has almost run dry. The district’s talent level is simply not where it was decades ago, when Jackson teamed up at Parkview with future Razorbacks like James Rouse, Rickey Williams, Bill Ingram and Anthony Chambers.

That kind of star power helped draw massive crowds in Jackson’s senior year of 1983, says John Kelley, Parkview’s head football coach from 1979 to 1998. Parkview rang up about $40,000 in gate receipts in 1983. Adjusting for inflation, that’s nearly $94,000 in today’s dollars. By comparison, Parkview football totaled about $7,000 in ticket sales last season. LRSD football clearly isn’t as popular as it used to be. Another sign: Parkview dressed 42 players for its season opener this fall. Thirty years ago, its junior varsity and sophomore teams each boasted more players. And Parkview is the program with the most recent success among LRSD schools.

Photo Gallery

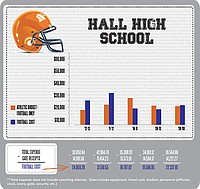

LRSD Football Budget Figures

At the start of each school year, all Little Rock School District football programs get a budget. Sometimes they spend more, sometimes less. The "cost" of football, as calculated here, includes money made off gate receipts. The total expense is how much each school spent before accounting for ticket sales. All data provided by the LRSD.

“It hurts me,” says Kelley, now a Parkview associate principal. “I was around when we were the schools that everybody wanted to teach and coach at. There was a lot of pride in our student bodies and things of this nature. There was a lot of pride.”

Similar stories pervade the district. Each program has had its gridiron glory years, and leaders there are grappling with how to bring them back. McClellan’s 75 football players have a new head coach and renewed enthusiasm after a former head coach, Anthony Chambers, was the driver in an August 2012 one-car crash in which one of his passengers died and several others were injured. In May 2013, Chambers was charged with negligent homicide. His plea and arraignment is scheduled for Sept. 24.

Chambers no longer coaches but still teaches at McClellan, the school’s athletic director, Frank Williams, says. “We have a new coaching staff of responsible, dedicated, organized gentlemen who vow to restore McClellan football to its prominence,” Williams says.

Of all LRSD high schools, Central appears to be in the best position to restore its prominence first. The Tigers won state titles in 2003 and 2004 before nosediving into a winless stretch in 2008 and 2009. The 2010 season brought in new head coach Scooter Register, who has helped renew some enthusiasm for the program. Central boasts about 150 players and beat Catholic High in its Sept. 6 season opener, but then lost to Bryant High School in week two.

The J.A. Fair War Eagles, like Central, had some recent success. Fair was a statewide powerhouse in the late 1990s, peaking in 1998 with a championship team featuring running back Cedric Cobbs. Then, like Central, Fair soon afterward dropped off.

The War Eagles’ recent fortunes — including a 6-74 record in the past six years — don’t appear to be improving any time soon. Yes, Fair won its season opener against nonconference foe North Pulaski High School 20-0, snapping a 22-game losing streak. But interim head coach Eric Redmon led the team, not the district’s longest tenured head coach, Donald Harris, who has coached Fair for 11 years. Harris wasn’t even on the sidelines. He says said he decided not to coach against North Pulaski — and wasn’t allowed to attend practice from Aug. 28 to Sept. 8 — after a disagreement he had with Fair adminstrators and some assistant coaches. “The tension between me and the coaches is real thick,” Harris says. “And the kids would have sensed that.”

Turnover among players has been a growing problem at some Little Rock schools. For instance, since turning into a magnet school in 1987, Parkview hasn’t had an attendance zone or defined neighborhood to draw its students from. Patriot student-athletes can, and sometimes do, transfer to play for other programs in central Arkansas. In the local prep scene, it’s common for coaches and players at one high school to pitch other programs’ best players on why they should transfer.

Charlie Johnson, a coach in the LRSD since 1973 and the War Eagles head basketball coach for the past 14 seasons, says this kind of recruiting has hurt Fair’s ability to compete in multiple sports. In football, the school no longer attracts and keeps talented football players like it did in the 1990s. In basketball, “there has been outright, blatant recruiting. It’s cost me two state [basketball] championships. I could have been ready to retire,” Johnson says. “If I went out around the state of Arkansas and got the 12 best players I could get, I don’t think I’d lose too many games.

“In football and basketball we are working the best we can with what we got,” he says. “It’s hard to keep my spirits up. I’m very discouraged.”

Turnover has also plagued some LRSD high school adminstrations. In recent years, there have been high turnover rates among principals at Fair, Hall and McClellan, says Johnny Johnson, the LRSD athletic director from 2001 to 2012. “Whenever you bring in a new principal, that lets that coaching staff basically get a reprieve because by the time you get a principal ready to make a change, that principal’s gone,” he says. “A new principal comes in, and they don’t want to make a change with somebody they’ve never seen or evaluated.”

Still, in the past 10 years, Hall has had the most turnover in head coaches. The Warriors have gone through six coaching changes as they seek their first winning season since 1993. One of those former Hall head coaches — John Daniels — is now working on reducing the turnover. The 49-year-old Daniels is a few months into his first year as LRSD athletic director after leaving coaching in 2006 for an LRSD administration job. Daniels says one change already made in his tenure involves the person who actually grades the performance of each school’s head football coach. Previously, the principal or assistant principals did the evaluating as the coach’s immediate supervisor. But Daniels will provide the annual feedback starting this school year.

In theory, this continuity in oversight should prevent Fair-like ineptitude from playing out too many years. Daniels says he hopes the change keeps more coaches in place longer, while helping them flourish. Daniels and other administrators, like LRSD Superintendent Dexter Suggs (also in his first year), want to make other changes, too. But they’re still gathering information. “At some point in time we’ll have a systemic plan that we’ll lay out there … that says, ‘Hey, this is exactly what we’re gonna do and this is how we’re gonna do it,’” Suggs says.

What would such a plan entail? For starters, making LRSD coaches’ pay more competitive with the state’s other big schools. In the 2012-13 season, LRSD head football coaches received stipends of $4,729 on top of their teaching salary. The chief assistant got $2,568, while other assistants got $2,162. Off-season coaching netted less than $2,000. These rates are below pay of similarly sized schools around the state, according to Johnny Johnson, now athletic director of the Russellville School District.

This makes it tough to attract coaching prospects and has left a few schools short of a full seven-coach staff. Parkview, for example, currently has five football coaches for three teams. “We couldn’t get anybody to apply,” says Kelley, who is also Parkview’s athletic administrator.

Low pay’s a culprit, yes. But so is a contract structure that complicates the process of adding a coach. LRSD coaches sign two contracts — one as a teacher and one as a coach. Many other districts around the state use only one contract for a teacher-coach. In those districts, if a teacher-coach resigns as a coach, he likely won’t be allowed to keep his teaching job, Johnny Johnson says. The LRSD has “allowed so many coaches to resign their coaching duties but keep their teaching duties,” he says. “When you’re getting ready to hire a new coach to replace that person who left, there’s not a teaching spot for that coach.”

This is Parkview’s situation. The contract arrangement has also created a work-around scenario where many LRSD coaches coach at one school and teach at another high school or middle school. At least 25 percent of district coaches “float” like this, according to Johnson and Kelley. These coaches don’t as often teach their players or see them around school. This separation makes it harder for coaches and players to bond.

District administrators plan to discuss the possibility of raising coaches’ pay in January, Daniels says. That raise could include a switch in the way coaches are paid, too. For 30 years, the district has been on a flat-stipend system, but Daniels and others will look at switching to a system based on a sports-specific percentage of a coach-teacher’s base salary. Many other districts use this “index” system. Johnson uses Russellville’s school district as an example of how it works. Let’s say a first-year teacher makes $33,000. If he is also a head football coach, then he’ll also get 26 percent of his salary as football-only pay. That equals $8,580, which is a little less than LRSD football pay before 1983, Kelley says. Before then, LRSD coaches were annually paid what amounts to about $9,000 in today’s money.

Money helps not only attract coaches, but parents, too.

Johnson says many LRSD sports facilities were allowed to sit dormant while local private schools and surrounding towns like Bryant, Maumelle, Benton and North Little Rock built more impressive stadiums, weight rooms and training rooms. “You take a potential [football player’s] parent, and you walk him through McClellan’s locker room or you walk him through Hall’s facilities, you walk him even through Central’s facilities and then you take him to one of the other schools. That parent’s gonna go, ‘I don’t believe I’d want to be going to Little Rock,’” he says.

Johnson adds he appreciated the help of a few companies — Verizon, Radiology Associates P.A., Regions Bank, Simmons Bank, Bank of the Ozarks — who donated money during his tenure to renovate LRSD facilities.

For decades, federal desegregation laws mandated all LRSD student-athletes be provided with buses to and from every game and practice. This transportation, which also applies to cheerleaders and drill team members, costs about $350,000 a year, Johnson says. He imagined what could have been possible had federal desegregation laws not made the LRSD one of the nation’s only districts with this kind of expense. As LRSD athletic director, Johnson wishes he could have used these funds instead on “updating our press boxes, upgrading equipment that our kids and coaches could use, putting in more turf fields, helping renovate gymnasiums. I mean, could you imagine if you had an extra $350,000 every year to dispose for athletic improvements?”

Keith Jackson has seen firsthand the difference between LRSD and private school sports. Two of his sons recently played football at Horace Mann Middle School and Little Rock Christian Academy. Koilan Jackson went to Mann; Kenyon Jackson attended Little Rock Christian. “They’ve got eight coaches over here [at Little Rock Christian],” Jackson says. “There’s three over there [at Horace Mann]. They’ve got a brand-new stadium made with turf over here. They’re practicing on a dirt field over at Horace Mann.”

Little Rock Christian, he adds, has “water brought in — paid-for water bottles — so their kids are very much hydrated. You’ve got a coach over [at Mann], with the hose on, saying, ‘The water’s running. Go ahead and get you a little water break.’ It’s warm water.”

“I’m sitting there going, ‘Man.’”

Jackson, like everybody else interviewed here, doesn’t want to be seen as an LRSD basher. He’s not. He and his wife, Melanie, very much believe in the district. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have sent their sons to Jackson’s alma mater.

Kenyon, a sophomore, and Koilan, a freshman, play for Parkview this fall. In all, there are 55 freshmen and sophomores on Parkview’s roster. Such youth can be a blessing if they stay together and develop in the future. But that’s not guaranteed in an age with so many other, potentially more attractive, programs out there. “How do you know a private school is not going to come get them?” Jackson says. “How do you know a school from across the river is not going o try to come and pull a couple of players from you?”

Given that Parkview has only 18 juniors and seniors on its roster, some Patriot freshmen will be pressed into varsity duty, as has been the case at other LRSD schools. The problem is they often aren’t yet physically ready or haven’t mastered the proper fundamentals. “The influx of ninth-graders is really what is hurting our program,” says Charlie Johnson, the assistant football coach at Fair. “We aren’t getting top-quality ninth-graders, and we aren’t getting that many. If they don’t get a chance to play in games, then you lose them. [But] they aren’t developed enough to play on Friday.”

Johnson adds: “If I had control of things, my solution would be to put those ninth-graders back to the junior high level. They would have their own team, their own schedules and a group of coaches where it would be strictly ninth-graders against ninth-graders.”

This won’t happen soon. Restructuring schools, or adding more athletic periods to the daily schedule, are changes well beyond the purview of district athletic departments. At this point, Daniels prefers to focus on smaller goals and getting more people in Little Rock on board with supporting LRSD football. He wants to discuss what his district has now, in terms of quality coaches and players, rather than harp on what’s lacking. “I can tell you that we are moving in the right direction,” he says. “It’s just a positive environment right now, for the most part. Everybody’s buying in.”

But will that optimism last even as the losses start piling up, as they seemingly always do this time of year? If the cheer holds up, then we have a sign: Maybe, just maybe, by the time Koilan and Kenyon are veterans on their Parkview team, they will experience something just as special as what their father felt all those nights ago in Quigley Stadium. Something so full of pageantry, chants, the swish and sway of pom-poms — that you swear if you bottled it and took it home, you’d never grow old.

In the 20th century, a palpable electricity ran through the biggest games between Little Rock public schools. Those goosebumps, and the glory, fled to other rivalries like Benton-Bryant and Bentonville-Fayetteville.

Some say the magic’s gone forever.

••••

Additional reporting by Nate Olson.

Evin Demirel writes more about local sports and society at thesportsseer.com.