Not long ago someone told me that if I ever wanted to ruin a person's day all I had to do was remind them that sometime, in the not very distant future, the world will be without Bill Murray. It worked on me. Not a day goes by that I don't contemplate the inevitable subtraction of joy from the planet that Murray's passing will bring. Were I a method actor, I might call up this thought to play a scene that called for resigned melancholy.

Of course we all understand that people will die. Intimations of mortality are part of what makes us human; they imbue our strivings with poignancy and make it possible for us to behave selflessly. We understand the fact of our own ending even if we do not quite believe in it. We know we are plunging into mystery.

And we suspect the world will survive our passing. Just as it survived the passings of John Wayne, Babe Ruth and Marilyn Monroe. Just as it will survive the passings of our grandchildren. This is our lot; no matter how desperately we cling to the light, it will one day be put out. This you must know, so you will be equipped to deal with the harshness of this life. It will end. In this way we are blessed.

Hearts are tough and stubborn things, but we should never be surprised when any particular heart is stopped. There is so much that can happen to them. But I never saw Robin Williams' suicide coming.

I haven't yet had the heart to familiarize myself with the particulars, I haven't read any account that has given many details about the circumstances surrounding his death. I know he was 63, and that he was, as the cliche goes, "battling depression." I heard he was having problems with alcohol. I guess he was very sad.

I do not know anything about depression. I do know that sometimes I get sad, and very often the cause of that sadness is something physical -- in my case, it's usually a lack of sleep. So I don't doubt those who say that clinical depression has very little to do with the circumstances of our lives -- how well and often we are loved, how much or little we worry about money -- and much to do with the chemicals that bathe our brains. I know that it doesn't matter if you are rich or beloved, something can still switch off in your brain and drop you into what seems like an inescapable pit.

This, they say, is what happened to Williams.

I do not have any stories to share about the man. I remember my wife, Karen, interviewed him once, in 1999, at the Ritz-Carlton in San Francisco, for the film Bicentennial Man. She remembers she made him laugh during that interview.

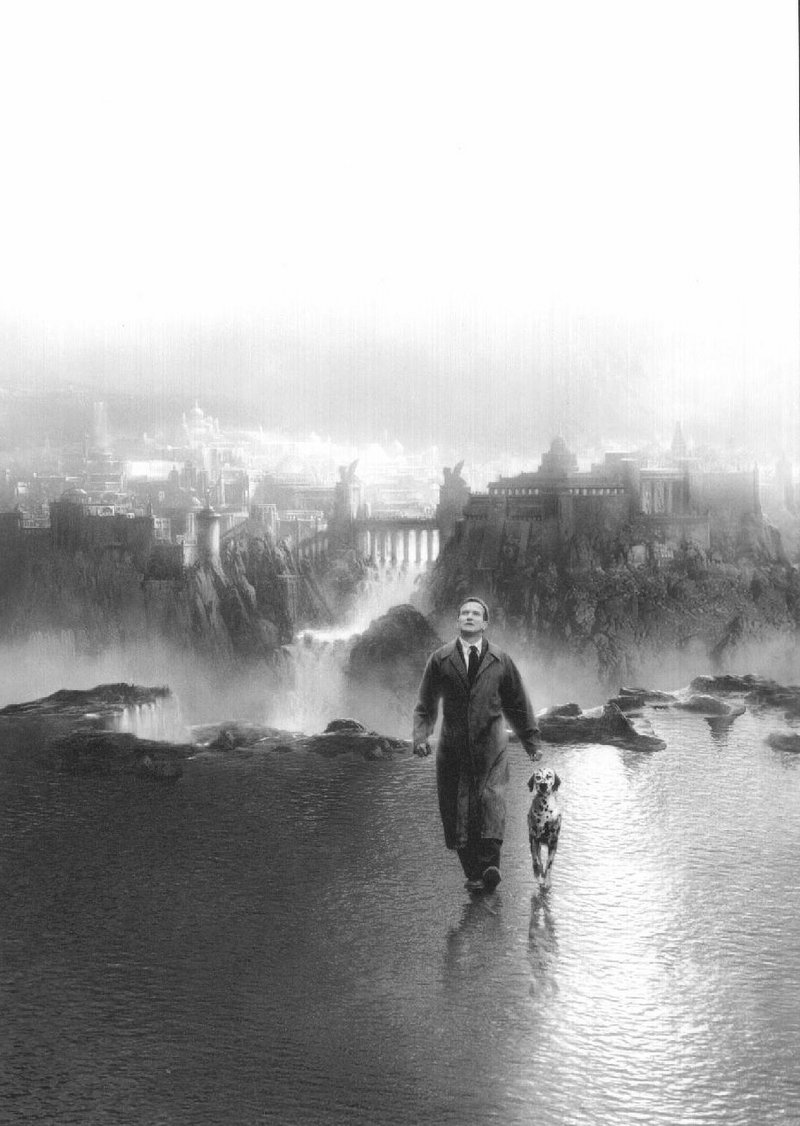

I don't remember much about that movie (according to the Rotten Tomatoes website and other online sources, I reviewed it, but I can't find the review in our online archive) except that it was based on the Isaac Asimov/Robert Silverberg novel The Positronic Man and it's about a robot, Andrew (Williams), designed to serve as a domestic servant and companion.

Andrew is not one of Williams' better film roles -- he was nominated for a Worst Actor Razzie for it. (He lost to Adam Sandler.) But he's not really bad in the movie either; Williams is not the problem with Bicentennial Man. The problem is the script runs to mawkish, especially in the second half after Williams emerges from the silicone cybersuit that makes Andrew look a little like C-3PO's beer-drinking college roommate.

Due to a quirk in his manufacture, the robot develops certain qualities -- creativity, self-awareness and emotions -- generally thought to be the province of people. He begins a legal struggle to be declared human. Ultimately this process -- which involves his changing out his seamlessly superior robotic parts for organic components -- costs him his immortality. To become fully human, Andrew must choose death.

Truth is, Williams was not well-used in the movies although he was wonderful in the '80s, beginning with his underrated turn as the title character in Robert Altman's delightfully bizarre Popeye. He was very good in Dead Poets Society; The World According to Garp; Good Morning, Vietnam; and Moscow on the Hudson. I was impressed by his understated turn in the 1986 adaptation of Saul Bellow's Seize the Day (which I believe was a cable television film).

Though he won a best supporting actor Oscar for Good Will Hunting, and he started out the decade with a fine turn in Awakenings and a great one in Terry Gilliam's The Fisher King, the '90s were not a good decade for Williams as an actor. Mrs. Doubtfire was a hit, but it made me cringe. Sitting through Patch Adams was one of the worst experiences I've ever had in a theater. Being Human was forgettable, Jumanji felt like a walk-through, Jakob the Liar was an ill-conceived fiasco. By the turn of the millennium, it was easy to agree with Roger Ebert's assessment: "Williams is a talented performer who moves me in the right roles but has a weakness for the wrong ones."

Williams could be a highly effective actor -- I liked him a lot in Bobcat Goldthwait's 2009 black comedy World's Greatest Dad, in which he plays a teacher who exploits the suicide of his unpleasant teenage son -- but his forte was as a stand-up comedian, a free-associator who ricocheted from one personality to another. Richard Pryor once described Williams the comic "as a comet bouncing off the walls."

Which may be another way of saying he needed those walls, limits he could careen into, jolting him off on an unpredictable tangent, like one of those reflex training balls athletes use to sharpen their reactions. It is not exactly a criticism to say that the movies may have been too big a canvas for Williams' best work -- he needed to work in the intimate, immediate present. He best served the movies when strong directors enforced the script, when he was contained within his character. But the camera arrested him. He could act, but Williams was best as an improvisational force.

It is easy for us to sit and speculate about the pain that seems to necessarily accompany great talent. That's something else I don't know about. I think we all feel pain, and that there are too many variables to come up with any easy sound bite about why anyone does anything.

I just know that Williams is no longer in the world. And that makes me sad.

Post script: The death of Lauren Bacall, which occurred after this column was written, evokes a different quality of sadness that I will address next week, either in this space or on our blog site, blooddirtangels.com.

Email:

pmartin@ arkansasonline.com

www.blooddirtangels.com

MovieStyle on 08/15/2014