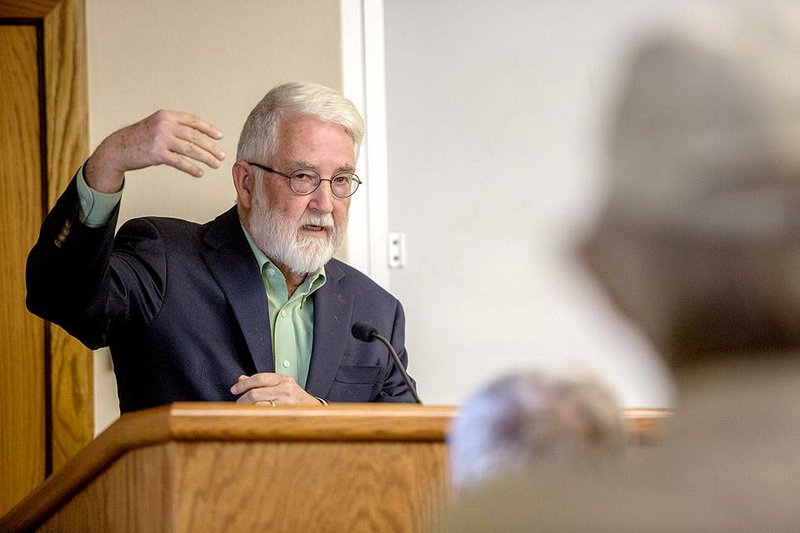

A daring 1850s plan to deliver mail to California using teams of stagecoaches faced challenges traveling a route through Northwest Arkansas, Tom Dillard, retired head of special collections at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, told a crowd Sunday at Hobbs State Park in Rogers.

But if the Boston Mountains and rough roads made for a difficult trek, stopping points at various locales offered travelers a welcome respite from hardships described vividly by passengers, Dillard said.

John Butterfield of the John Butterfield Company successfully won a bid in 1857 to deliver mail from Missouri and Memphis to San Francisco, with the U.S. Congress agreeing to pay the company $600,000 yearly for the service.

"He had a whole lot riding on it," Dillard told a crowd of about 60 gathered in the state park's visitors center. Dillard described the payment amount as a "gigantic sum" for the time period.

The undertaking of the Butterfield Overland Stage was no sure thing, however. While stagecoaches were common at the time in Arkansas, Dillard said, the entire venture had to be built up in a year to satisfy the government -- which also demanded that a one-way trip take no more than 25 days, quite the feat at the time.

A southern route helped meet another requirement that deliveries be made year-round, though Dillard said sectionalism and politics also likely were factors in how the route took shape. But with Memphis and St. Louis as starting points, it made sense for Arkansas, as a state bordering both Tennessee and Missouri, to be included, Dillard said.

The plan involved amassing some 1,800 head of stock, including both horses and mules, with the idea that fresh animals could be swapped along the approximately 2,800-mile journey, which included overnight travel.

"They needed the tenacity that mules brought," Dillard said, noting the difficulty of the terrain at times.

Passengers could also board the coaches, paying $200 for a one-way trip. But with a focus on mail delivery, each person was allotted only 15 inches of space to sit on the coach, Dillard said.

Stagecoaches lacked springs for a suspension system, instead relying on leather straps that produced a characteristic swaying motion during travel. Dillard said passengers on a long journey required time to adjust once it was over so they could again walk normally.

"To us, that would seem maddening," Dillard said, though he added that the suspension system at least helped somewhat with the jolts experienced on the rough roads.

Yet despite efforts in advance of the inaugural trip, like cutting overhead trees along routes, the rugged nature of the land made hardship inevitable, Dillard said. Passengers who agreed to travel were expected to help out if a coach faced an impassable road.

Sometimes lightening the load made for easier coach travels -- which were generally done with horses at a trot -- meant that passengers could end up walking for long stretches.

From Missouri, the inaugural trip began exactly one year after Butterfield won the bid to provide mail service. The journey had its first stop in Arkansas at a site known as Callahan's Tavern in present-day Rogers, Dillard said.

Another station site, Fitzgerald's Station, included a native stone barn that still stands today in what is now Springdale.

However, such historical sites associated with the Butterfield Overland Stage are relatively rare, Dillard said.

"There are just not many of them left in the whole country," he said.

Fayetteville was considered a bustling town at point in history and became a divisional headquarters for the venture, Dillard said.

Hogeye became a popular stop, apparently because of excellent food provided there, Dillard said.

One report of travel along the Boston Mountains described the route harshly. According to the report, "It was impossible that any road could be worse," Dillard said.

In all, the trip from Fayetteville to Fort Smith took about 14 hours, Dillard said.

But it was only one part of the lengthy journey described as taking 23 days and 23 hours, Dillard said.

Ultimately, while Butterfield had been granted a six-year contract, the Butterfield Overland Stage lasted only three years as the nation plunged into the Civil War and other routes grew into favor.

NW News on 12/01/2014