HEBER SPRINGS - The Metroplan board of directors voted Wednesday to remove the long-sought North Belt Freeway from the long-term transportation plan that is used to guide the development of road construction projects in central Arkansas after a new study found it would cost $648 million to build as a toll road.

Under federal rules, the project needs to be on the region’s long-range transportation plan before it can be built. A final vote on the plan by the board of the region’s transportation planning agency isn’t expected until December.

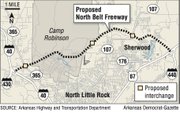

The Arkansas Highway Commission also likely will review the study, which assessed the feasibility of building the North Belt as a toll road, and have its own say on the future of the 13-mile route connecting U.S. 67/167 and Interstate 40 west through parts of Sherwood, Camp Robinson and North Little Rock, and long deemed a regionally significant project.

The study, released Wednesday at the annual retreat of the Metroplan’s board, found that combining the construction costs with other costs left toll revenue generated from the projected traffic short by $500 million, a gap that local officials say is too large to fill.

Jim McKenzie, the executive director of Metroplan, stopped short of calling the project dead, however.

“The North Belt Freeway is like the great zombie roadway project,” McKenzie told the board, which is composed of the mayors and county judges in Pulaski, Faulkner, Saline and Lonoke counties. “It’s not really dead, but it’s not alive, either.”

The vote allows McKenzie’s agency to put the long range transportation plan out for public comment this summer without the North Belt Freeway. But the North Belt could be revived if the board decides to include it in the plan before a final vote in December.

“It will be a zombie until we adopt our new plan,” McKenzie said after the meeting.

Removing the project from the plan will free land for development that has been set aside under local zoning regulations for the project, McKenzie said.

Board members initially balked at removing the North Belt from the long-range plan, which covers projects and development through 2040, unless other projects replaced it to account for increased traffic in the region.

“We have got to beef up [Arkansas 107],” said Conway Mayor Tab Townsell. “We’ve got to beef up [Arkansas] 89. There is a gap if we don’t replace the North Belt.”

Sherwood Mayor Virginia Hillman backed the amended proposal the board approved.

“We’ve got to have an alternative because there’s no way to pay for the North Belt,” she said.

The state and Metroplan already have spent millions of dollars on the project. In 2012, the state Highway and Transportation Department said it had spent $5.9 million on right-of-way acquisition since 2008, when the Federal Highway Administration approved the route. The latest total spent on the project was unavailable Wednesday afternoon.

The new cost estimates for the North Belt were contained in a study to assess the feasibility of tolling the route. The Highway Department and Metroplan each agreed to split the cost of the study, which was estimated at $500,000.

In January 2013, the commission selected Atkins North America of Austin, Texas, to conduct the study. Public Financial Management of New York also contributed to the study.

The study assumed the route would be open to traffic by 2020, with the years 2016 through 2019 spent on project development, which study authors said was “aggressive.” It pegged the cost of environmental clearance, preliminary engineering, final engineering, rights of way, construction engineering and inspection and actual construction at $647.9 million, when inflation is taken into account.

The costs are higher than normal because of the location of the route, which would require bridges through areas that are environmentally sensitive or, like the National Guard’s Camp Robinson, have little right-of-way area available.

“I was surprised at the revised construction numbers,” McKenzie said. “I think that took everybody aback.”

For perspective, when the project was on the list of a highway-improvement plan the Legislature adopted in 1991, its price tag was $55 million. Less than 10 years later, one part of the route - from U.S. 67/167 east to Interstate 40 - was built for $65 million.

According to the study released Wednesday, the tolls on the beltway would be collected electronically with no tollbooths available or cash collection allowed and assumes a 20-cent cost per mile for passenger vehicles and four gantry locations. Gantries are the equipment used to assess tolls electronically. Vehicles would have to be equipped with transponders to allow electronic toll collection.

Other costs associated with the tolls include the installation of fiber-optic lines, a host system to process the transactions, a customer-service center and equipment for a video-processing center. State law would have to be changed to allow motorists who don’t pay to be assessed a fine through video identification of license tags, the study authors said.

Further, the study looked at the life-cycle costs of the project, including periodically replacing the toll equipment as well as maintaining and periodically replacing the pavement.

It would cost a motorist in a passenger vehicle $2.46 to travel the entire route in 2020. The study authors said that above that price point too many motorists would elect to divert to toll-free routes. By 2030, the cost would be $3.34, according to the study.

Average daily traffic on the North Belt in 2020 was projected to be 24,900 on its busiest segment near Interstate 40 west if the route was tolled; it would reach 33,800 if it was a toll-free route, the study found. By 2030, that segment would see 30,600 toll-paying motorists; if it was toll-free, the average daily traffic would reach 42,400.

In the first five years of operation, from 2020 to 2025, it projected the route would receive $108.1 million in revenue from tolls. That figure would rise to nearly $538 million by the 2051-to-2055 time frame. From 2020 to 2055, or its first 35 years, it would receive nearly $2 billion in toll revenue. Those years are used because the study assumes 40-year bonds issued in 2016 to finance the project.

Still, the study looked at three approaches to financing the project, including some public resources providing backup in case the bonds couldn’t be supported by the revenue. In two cases, the best bond rating was BBB, which would result in higher interests costs above 7 percent, the study found. With those ratings, the funding gap ranged from $517.5 million to $561.7 million.

Using some source of public credit to enhance the bond issue and give the issue an A rating left a gap of $453.1 million, the study said.

To go forward with the project, “you would need significant external funding,” said Scott Trommer, an executive with Public Financial Management.

The problem is the North Belt is a “fairly expensive project,” given its scope, and won’t generate the traffic needed to finance it, said Steve Austin, an Atkins North America executive who worked on the study.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 03/20/2014