I don't generally believe in fate, but I find it hard not to believe that Francis Scott Key was placed on this earth to see the exciting and horrible moment when the British bombardment of Baltimore's Fort McHenry started at 6:30 a.m. September 13, 1814.

It was the most frightening episode of the War of 1812 and, by the time of its conclusion, the inspiration for Key to write a poem that eventually became the United States' national anthem.

On August 24-25, 1814, British forces captured and burned Washington, D.C., in response to the burning of a Canadian town. The British then moved on Baltimore, planning a combined land and sea assault. The British army found a formidable Maryland militia and U.S. army presence, so they stopped to allow the British fleet to soften up the Baltimore defenses.

The fleet numbered 40 ships in the Chesapeake Bay, but because of the shallows of Baltimore Harbor, only 16 vessels moved on Baltimore: five bomb ketches, 10 small warships, and the HMS Erebus, a vessel adapted for firing Congreve rockets, oversized stick-guided fireworks with either

incendiary or anti-personnel warheads. These ketches were fairly simple affairs--reinforced ships with two massive mortars on either side of the mid-line. Indicative of their supposed destructive power, they carried the names Terror, Volcano, Meteor, Devastation, and Aetna. They had particularly large mainmasts because the foremasts were absent so as not to obstruct the mortar fire.

The mortars fired bombs, lofting them on a high trajectory as far as 4,000 yards, well beyond the range of any of the cannons at Fort McHenry. These bombs were stuffed with gunpowder, and the fuses had to be lit before the mortars were fired. The idea was to light the fuse with such timing that the bomb exploded immediately over the target. Light it too late and some brave enemy soldier could run up to the bomb after it plunged to earth and extract the fuse before the fire reached the powder; light it too early and the bomb would explode prematurely, sending deadly shrapnel into its immediate surroundings.

At 6:30 a.m. September 13, the bombardment started. For 25 hours the 10 mortars rained fire upon the fort, with only a couple of interludes of quiet. The thousand men in the fort knew the rounds were on their way by the exploding propellant. It took many seconds for the bombs to arrive. Good eyes might follow the flight of the projectiles as the sparks from the burning fuses traced through the night sky.

The heightened anticipation--up to 1,800 rounds left these warships to batter the fort into submission--must have worn these men down. And the interested observer, with his heart in Baltimore, shared the same anguish. Was the fort being turned into rubble? Would the city be next? Upon his appointment as commander of the fort, George Armistead had ordered two flags made, one small storm flag and a much larger garrison flag. From beyond the fort, these flags were the only indication of American survival. During that difficult night, the storm flag waved, but at dawn Armistead ordered the garrison flag raised. Fifteen stars and fifteen stripes.

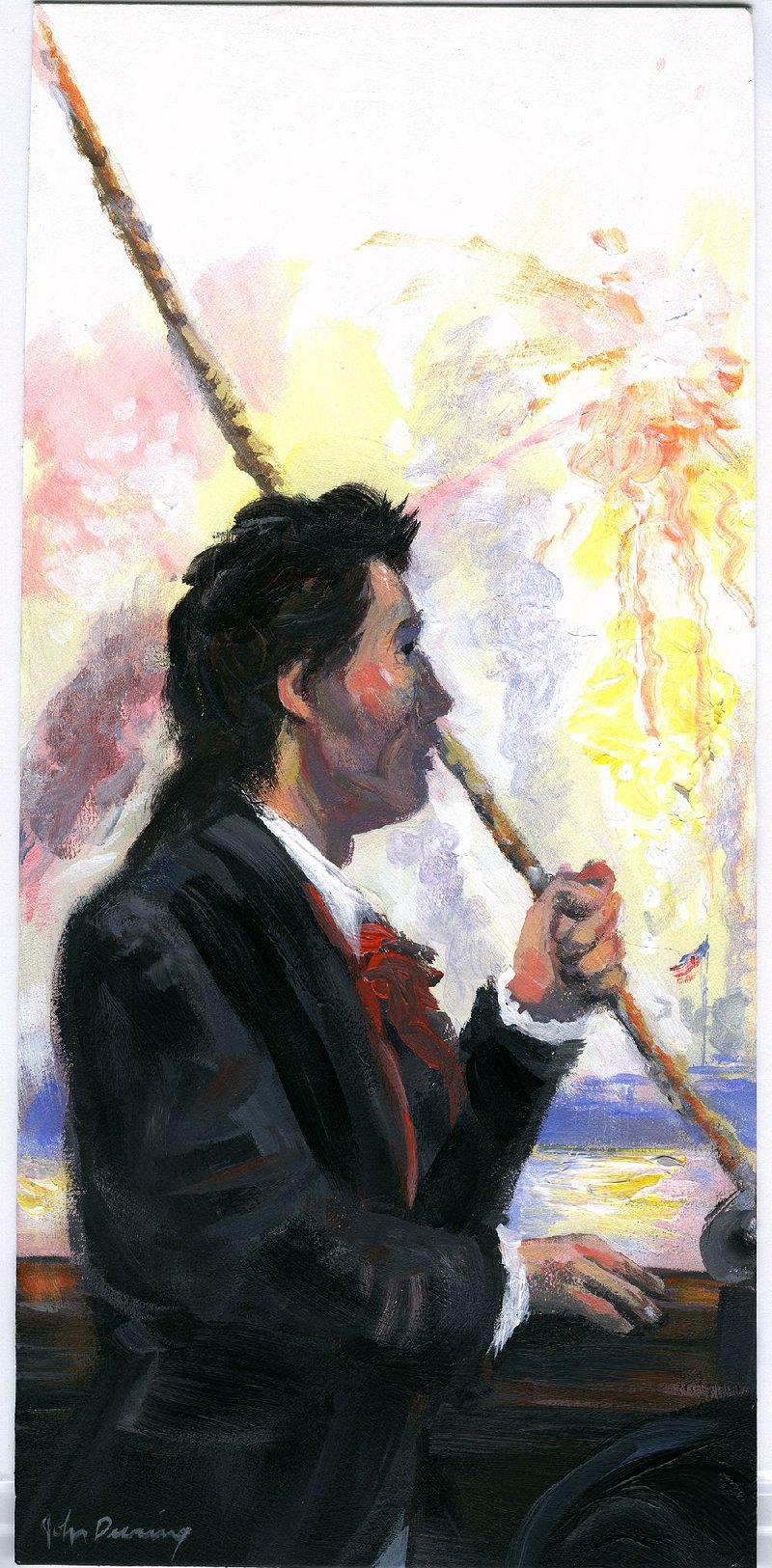

Key witnessed by telescope the British assault on the country's third largest city. He was eight miles away, gripped by the uncertainty. All day and into the night, the bombardment continued. Twice during the night, indications of resistance came from the fort and from nearby batteries. But they too fell silent and mortars began again.

All night Key watched. At dawn he could finally see the fort for himself, without the British pyrotechnics. He had a question:

Oh, say, can you see, by the dawn's early light,

What so proudly we hail'd at the twilight's last gleaming?

We saw it yesterday, can you still see it this morning?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars, thro' the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watch'd, were so gallantly streaming?

Yes, we're talking about the flag with the stars and stripes flying over Fort McHenry.

And the rockets' red glare

Those Congreve rockets shot from the HMS Erbus provided the "red glare."

the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof thro' the night [those darn bombs did provide some illumination] that our flag was still there.

O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave ...

The flag wasn't a big deal in the first few years of the nation. It marked our ships and forts. The celebrity of Betsy Ross was decades away, and the Pledge of Allegiance far more distant still. What Key did was to give the flag a name and a personal meaning. It was now more than an official emblem. It had a starring role in a great survival drama as it defined the experience of thousands of individuals who had shared in the formidable assault. The young nation needed a symbol of pride and national unity, and the victory in Baltimore gave it to us. The flag flew both over Baltimore and "O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave."

Don't talk to me about replacing this anthem with some singable song or a country and western production with all the right chord changes. I want to be in this galvanizing moment, to be reminded that this country not only survives, but demands something from us. This poem calls us to be if not fighters, at least witnesses. Don't turn away from the ramparts, don't turn away from the danger or discomfort, don't turn away from civic engagement.

"Can you see?" The basic requirement of a functioning democracy is the attention of its citizens. How interesting it is that at so many ceremonies and events the singing of the first verse of the Anthem asks if we are attentive, and then leaves us with another question: "Does that star-spangled banner yet wave, o'er the land of the free and the home of the brave?" The answers are left to us.

Some call the War of 1812 the Second War for Independence, as the self-concept of a nation coalesced in the struggle. And how valuable was the flag and the poem in this process? The poem was shared with Baltimore soldiers within days of the battle, and publicly performed with music the next month. It caused an immediate sensation, eventually becoming our National Anthem. A gift of the War of 1812.

Arkansas had its own musical contribution borne of the conflict, yet somewhat late in its arrival. In 1936 a song was written to help teach history, and to remind students the difference between the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. When recorded 20 years later, the song received some small notoriety, but when picked up by an established recording artist, it took off.

"In 1814 we took a little trip, along with Col. Jackson down the mighty Mississip...." I'm referring to the song that built the Ozark Folk Center--"The Battle of New Orleans." Jimmy Driftwood wrote the song, Johnny Horton took it to the top of the Billboard charts in 1959, and the song won a Grammy. Thanks to the War of 1812.

Bill Worthen is director of Historic Arkansas Museum.

Editorial on 09/07/2014