BENTONVILLE -- It is hard to imagine two artists further apart than Jamie Wyeth and Andy Warhol.

Yet, here they are, in adjoining exhibitions running concurrently through Oct. 5 at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

‘Jamie Wyeth’

‘Warhol’s Nature’

Through Oct. 5, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 600 Museum Way, Bentonville

Hours: 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday and Thursday, 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Wednesday and Friday, 10 a.m. -6 p.m. Saturday-Sunday; closed Tuesday

Admission: $8, free for 18 and under and members for both exhibitions. Regular museum admission is free.

Info: crystalbridges.org, (479) 418-5700

Wyeth, third in a revered American painting dynasty led by grandfather N.C. Wyeth and father Andrew Wyeth, is rooted in rural places -- Chadds Ford, Pa., and the rugged Maine shore. Jamie Wyeth is a superb painter known for realistic canvases imbued with mystery and psychological drama.

Warhol, instigator of America's pop art movement, practiced an assembly line work ethic in his studio, The Factory, in New York City. There he created vivid works that reflected the country's obsession with consumerism and celebrity. Wyeth was a part of that scene in the mid-1970s; his friendship with Warhol endured until Warhol's death in 1987.

Wyeth is delighted that Crystal Bridges has brought them together.

"I think it's pretty wonderful," Wyeth, 69, says. "Andy would have loved the idea."

As he moved through the galleries displaying "Warhol's Nature," an exhibition created by Crystal Bridges curator Chad Alligood, Wyeth radiated a boyish charm, a warm laugh and enthusiasm; his face lit up as he told stories about Warhol.

But in an interview after the walk-through, Wyeth's effusive manner darkened a bit as he discussed the experience of seeing his work in "Jamie Wyeth," a retrospective organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which is ending its year-plus tour in Arkansas.

"The first time I walked through the show [in Boston] I was terrified," he says. "It's your whole life out there. These [paintings] were all obsessions of mine at the time I worked on them, the most important things in my life. I extinguished myself on them, then moved on."

Those feelings haven't changed, but he is "very happy" with the exhibition's installation.

"They've done a remarkable job, it is beautifully lit. But seeing several rooms of these obsessions is not a comfortable feeling, I don't much like it. My writer friends say it's like walking into a room full of people reading your novel while you're standing there."

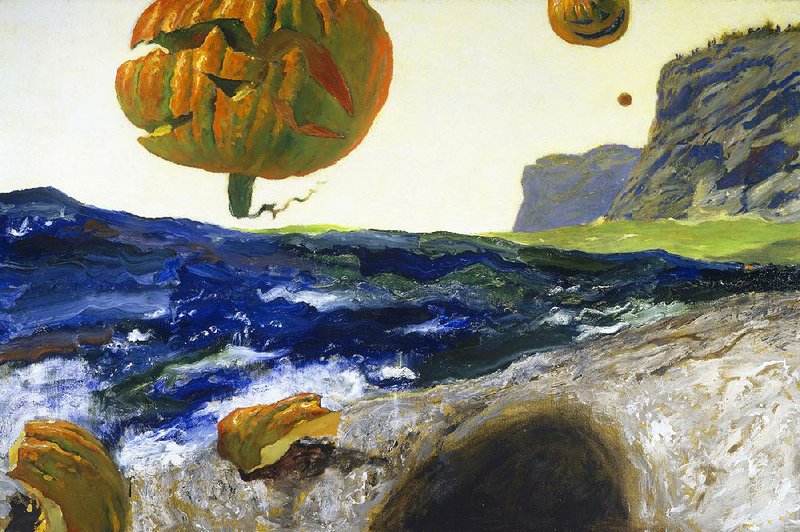

Among the "obsessions" are familiar, beautifully painted works -- masterful portraits of John F. Kennedy, Warhol, dancer Rudolph Nureyev, and his wife, Phyllis Mills Wyeth; potent landscapes such as The Headlands of Monhegan, a Maine island seascape with tumbling pumpkins, and a series of works inspired by dreams, including three that have depictions of his father, grandfather, Winslow Homer and Warhol.

Curator Elliot Bostwick Davis of the Boston museum organized the Wyeth retrospective and is enthusiastic about the pairing of the two shows.

"It is fantastic to have Wyeth and Warhol together; the fact Jamie's still very much mining those years for inspiration and how he stepped out of Chadds Ford and took his life to The Factory, is fascinating."

Davis, also chairman of the museum's Art of the Americas wing, says a fine example of the connection between the two artists is Wyeth's Bale, a luminous painting of a hay bale on Wyeth's farm.

"Hay bales are repetitive, endless, seemingly the same every time ... like Warhol's Brillo boxes, soup cans, cornflakes boxes," she says.

Davis describes it as an unexpected overlap between the subjects. "But it's there. They took inspiration from one another."

...

Andrew Wyeth didn't understand.

"He wondered why I wanted to go to New York City, why I wanted to live that life," Wyeth says, of his father.

A spirit of rebellion was part of it, he says.

Wyeth was introduced to Warhol by a friend they had in common, photographer Peter Beard.

"Andy was something out of Halloween, his look and incredible costume, I loved all of that," Wyeth says, noting that Warhol's appearance fit right in with his family's love of Halloween and dressing up for that holiday.

"Andy had this completely secret life. The more I got to know him, the more secretive I realized he was. I lived just down the street from Andy. As well as I got to know him, I was only in his house three times. It was a beautiful five-story townhouse. Inside was a rabbit warren of stuff he collected, you had to literally go through tunnels. Among that stuff there would be some complete crap and then some fabulous stuff and some wonderful paintings."

Occasionally, Warhol visited Wyeth's farm.

"He adored my father's work, that was all real painting, and he was very excited by that," Wyeth says.

"I found him terribly sweet; his sense of wonder was amazing. That's where he resonates today with young people. Warhol had a 'gee whiz' sense of wonder ... if Liz [Elizabeth Taylor] looks good once, why don't we do her image 50 times?"

In "Warhol's Nature," an elegantly posed taxidermied Great Dane commands attention as it stands in a Plexiglas enclosure near several art works of the animal created by Warhol. Wyeth remembers the dog's prominent presence in The Factory.

The dog was named Cecil, after movie director Cecil B. DeMille, who supposedly owned the dog.

"Andy and I spent days, hours, going through antique stores and buying taxidermied dogs and cats," Wyeth says, laughing. "He was kind of horrified by it, but they were all over The Factory. It must have been the rage in the 1930s to take your pet to the taxidermist after it died. One that I have has its name, date of birth and death with it."

During that time, Wyeth was also drawing human anatomy at a morgue.

"Andy was mortified, aghast," Wyeth says. "'Why are you doing that?' he would ask." Some of those drawings are in the exhibition.

...

The abundance of drawings in the Wyeth exhibition illuminates the artist's process and the development of his artistic vision. Curator Davis previously worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's drawings department and has studied childhood drawings of Winslow Homer and Edward Hopper.

"Jamie's mother saved 1,100 drawings from his childhood," Davis says. "It's a window into artistic personality. I am curious about experiences that form an artistic mind and wanted to show how a creative mind evolves."

That evolution's roots began where Wyeth grew up, on the family farm in Chadds Ford in the renowned Brandywine Valley in Pennsylvania. He started drawing at age 3, and after the sixth grade, his father took him out of school.

"My mother was horrified, very much against me being pulled out of school," he says. "Back then, home schooling was unheard of. I had to be tested [by the state] every six months. My father felt since I was going to be a painter, there was no need for me to go to school." He studied for a time with his Aunt Carolyn, an accomplished painter in her own right.

Family history was repeating itself. His grandfather, N.C. Wyeth, schooled Andrew (made frail by whooping cough and resulting chronic bronchial problems) at home.

"N.C. wanted to keep him nearby; I've heard it was because of my father's illness, but I think it was a case of [N.C.] wanting control of his son," Wyeth says.

So much so that when Andrew Wyeth fell in love and wanted to marry, N.C. discouraged it.

"He told my dad he should never marry. 'I will support you, you need to paint,' he told him."

Wyeth says his father was "the antithesis of that with me."

That experience, Wyeth says, may well have spurred Andrew to distance himself from N.C. artistically.

"There was no sign of N.C. Wyeth in my father's work, nothing. Almost consciously so. My grandfather was all about color; dad was browns. But no one knew N.C. Wyeth's work better than my father. He hero-worshipped my grandfather."

That difference reflected itself in their studios.

"N.C.'s studio has these huge scaffolds, costumes, guns, compasses. Go into Andrew's, and it's four gray walls. Nothing else. It was a lot more exciting at N.C.'s studio. To me, as a child, it was a real artist's studio. I'd go home, and dad was painting a dead bird."

Wyeth's oil painting, The Children's Illustrator (2005), depicts his grandfather's studio. A lavender-colored light -- a signature N.C. Wyeth color -- streams through the window.

Wyeth says that artistically he feels closer to his grandfather. "My dad was a very strange, a very peculiar painter," he says. "The fact they call him a realist is pretty absurd. He was almost a primitive; that quality is in his work."

Curator Alligood describes Jamie Wyeth's art as "sensual, not austere like his father's work. There is a psychology, personal narrative you don't get from Andrew."

What does Wyeth consider the most important lessons he learned from his father and grandfather?

"The complete absorption into whatever you are doing. I saw that with my father, painting was everything, that's all my father did. He created a crisp and lean kind of world, and that intrigued me. I learned from them to sharpen your tools, hone your talent, keep working ... I have to push myself sometimes ... with no boss to push you, you have to push yourself.

"Rather like a ballet dancer, you have to exercise, you have to practice so that when things happen, you are ready. Then, once in a while, things become alive. That I've learned from them; my dad by watching him work."

When more than 200 paintings and drawings by Andrew Wyeth of a neighbor, Helga Testorf, surfaced in the mid-1980s, the sensual images sent shockwaves through the art world.

"It was wonderful," Wyeth says. "I was intrigued. Dad had a secret life, that was powerful."

What's next for Wyeth? Or is that a secret?

"No, not at all," he says, laughing. "I'm wildly excited about what I'm working on now. I've always been fascinated by screen doors. I'm taking real screen doors, painting people behind them. The first one is Andy ... it's kind of ghostly. The idea bothers some people ... they come into the house, see the door, open it ... 'Oh my God, there's someone behind there.' I'm getting completely carried away with that."

Alligood says the exhibitions show that the American spirit in art "is very broad."

"Wyeth is an American painter par excellence; his landscapes, his subjects are American. Warhol -- so American in his approach to the world, consumer culture, celebrity, nature.

"They both are iconically American."

Style on 08/09/2015