CORRECTION: Gov. Asa Hutchinson said at a news conference that his objective in regards to death-row executions is to carry out the law and ensure that the “system works, that innocence is protected, guilt is established.” He was misquoted in this article.

The Arkansas Department of Correction has obtained the drugs and set the protocol for lethal injection, paving the way for executions to resume in the state after a 10-year hiatus, state officials said Thursday.

Attorney General Leslie Rutledge can now submit a letter to Gov. Asa Hutchinson with names of individuals on death row and ask that execution dates be set.

Rutledge had not made any execution requests as of late Thursday, said Judd Deere, spokesman for the attorney general's office.

Hutchinson said at a news conference Thursday at the state Capitol that he had a "conversation with Rutledge on Wednesday" and that he expects to see "in the coming week or so one or more requests for dates to be set."

Neither Hutchinson nor Rutledge identified which requests could come up.

Of the 34 inmates on death row, eight have exhausted all appeals and can be scheduled for execution, Deere said.

"Whether or not we will submit all eight as a group at once or each on an individual basis has not been determined," he said.

Hutchinson cautioned that the path to the next execution in Arkansas could be a long process.

"Once I get a request, we'll set a date. I would expect there will be further challenges in court, but those challenges are always delayed unless you set a date," Hutchinson said. "While the Legislature passed a law that I signed that kept the sources of the drugs confidential, I am sure that there might be some challenges to that.

"I guess there is always one working through the courts, so I understand there will be additional challenges. But it is important to have a date set because it keeps the process moving so that ultimately the law can be faithfully carried out."

The last execution -- Eric Nance, convicted of murdering 18-year-old Julie Heath of Malvern in 1993 -- was carried out in November 2005 by using a three-drug cocktail of phenobarbital, a paralytic agent and potassium chloride.

Arkansas has not put anyone to death since then because of legal challenges to the state's death-penalty procedures. The use of the drug midazolam was challenged in federal court because death-penalty opponents claimed that the drug does not induce a complete level of unconsciousness, which allows the inmate to feel pain.

Arkansas Act 1096, passed in April, shields the state from disclosing any information that may identify the source of drugs in executions. The Act allows the state to use either a barbiturate or the drug midazolam, followed by two other drugs, to put inmates to death.

A June 30 invoice from the Correction Department shows the state spent $24,226.40 for three drugs: potassium chloride, vecuronium bromide and midazolam. The name and address of the supplier, however, was redacted.

Midazolam has a shelf life of three years, according to the federal safety data sheet for that drug. The invoice supplied by the Correction Department on Thursday does not show the manufacturing date of the drugs that were purchased.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in an Oklahoma case that midazolam can be used in executions without violating the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.

Shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling, an attorney for nine Arkansas death-row inmates filed a lawsuit challenging lethal injections.

The lawsuit, filed in Pulaski County Circuit Court against the Arkansas Correction Department and its director, Wendy Kelley, seeks a permanent injunction against executions under Arkansas Act 1096 of 2015 and demands that the Correction Department reveal its source when purchasing future execution drugs.

To settle a previous lawsuit by the same inmates, the Correction Department agreed in 2013 to reveal the source of any future execution drugs.

The Correction Department said in recent court documents that the passage of Arkansas Act 1096 prohibits the release of the information.

Jeff Rosenzweig, the inmates' attorney, said Thursday, "We are entitled to know where the state got the drugs and whether they acquired them from a reputable vendor. The question is this: Is the drug going to cause extraordinary pain and suffering, which violates the Eighth Amendment. You cannot torture someone to death."

In 2011, the state had to relinquish its supply of sodium thiopental -- one of three key drugs that were used in a lethal injection cocktail -- to U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agents. The Arkansas Correction Department had obtained the drug from Dream Pharma -- a wholesale drug supplier that was run out of a driving academy's offices in London, according to court documents. British authorities had banned exports of the drug in November 2010.

A nationwide shortage of lethal injection drugs as well as pressure from death penalty opponents on pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs led prison officials nationwide to seek alternative sources or different drugs or combinations.

Midazolam was first used in 2013 in Florida execution.

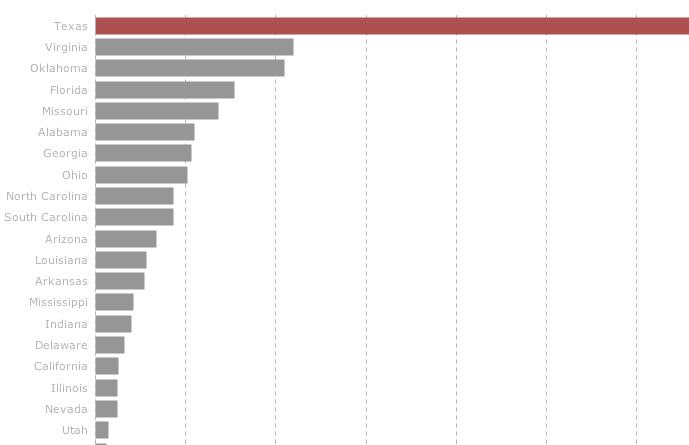

Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana and Virginia allow the use of midazolam but never have used it in executions. Arizona, Florida, Ohio and Oklahoma have executed inmates using midazolam.

The case that prompted the June U.S. Supreme Court decision stemmed from the Oklahoma execution of Clayton Lockett. That state used midazolam.

Lockett died after 43 minutes. His body convulsed, he moaned, and he clenched his teeth for several minutes before prison officials stopped the process. Executions in Arizona and Ohio using the drug also went longer than expected.

A review later determined that the IV line used to deliver the drug was not properly placed.

In Ohio last year, officials used midazolam. The inmate appeared unconscious but then made loud choking noises before being pronounced dead.

During a 1992 execution of Rickey Ray Rector in Arkansas, executioners made nine needle marks on Rector's hands and a 2-inch wide incision on the inside of his right arm while trying to find a vein. Officials eventually inserted the needle in a vein on top of Rector's right hand.

According to the Arkansas Correction Department's latest lethal injection procedures -- finalized on Aug. 6 -- "every effort will be extended to the condemned inmate to ensure that no unnecessary pain or suffering is inflicted by the IV procedure." The local anesthetic Lidocaine will be "accommodated as necessary," the procedures read.

The protocol also outlines steps to be taken to ensure the inmate is unconscious and procedures to be taken if a problem arises.

Rosenzweig said if the state decides to proceed with an execution before his clients' suit is decided, he is ready to fight.

"We hope no one will try to rush this thing," he said. "If an execution is scheduled, we would file a motion in the appropriate court to seek a stay. I think it's important that we get these issues resolved."

Hutchinson said Thursday he had not thought about what the next execution would be like. His objective, he said, is to carry out the law and ensure that the "system works, that innocence is established, guilt is established" and that the inmates have competent counsel and the system is reviewed.

A Section on 08/14/2015