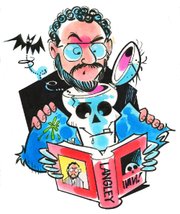

Travis Langley is the brains behind this outfit -- these dozens of fellow psychologists and related experts brought together to analyze the effects of a zombie plague.

Langley, professor of psychology at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, is editor of the anthology The Walking Dead Psychology: Psych of the Living Dead (Sterling , $14.95).

A half dozen of the book's 27 writers of chapters and features are from Arkansas, or have Arkansas connections. The scope is national, but Arkansas is a natural place to think about zombies, he says.

"When the zombies attack a farm house, we say, 'I know that farm house.'"

Zombies are mindless creatures, but they cause all sorts of extreme reactions in the minds of people trying to survive a zombie attack.

The book's focus is "mostly on living characters," Langley says. He and his colleagues look at the shambling consequences of a zombie infestation in the AMC cable television series The Walking Dead, based on the comic book series by Robert Kirkman. The sixth season starts Oct. 11.

The show is a way to address one of psychology's basic questions, Langley says:

''What makes a human being human?

This leads to a second point of soul searching as the living find themselves behaving like monsters themselves in order to survive: "What does it take to retain your humanity when you've got trauma after trauma happening?" Langley asks.

Characters including Rick, the sheriff, and Daryl, the survivalist, have to fend off zombies. But who doesn't feel like a real-life Rick some days, desperately wanting out of a bad situation; or like Daryl with a bunch of troubles snapping at him?

Daryl's answer is to let fly with his crossbow. And who hasn't imagined some equally drastic solution to a problem, only to stop short of acting, well -- crazy?

Real-life traumas and dangerous emotions can be hard to talk about in class, Langley says. He finds "the topic can be so unpleasant, they miss the point of what I'm saying."

In that case, he calls on fictional characters as teaching aides. Superheroes and zombies join the faculty.

If the lesson relates to criminal behavior, the

professor might couch his lecture in terms of Batman and the crime-fighter's arch enemy, The Joker. (Langley's previous book, Batman and Psychology: A Dark and Stormy Knight (Wiley, 2012), accounts for his office decor, a collection of Batmobiles.)

Psychology can't tell for sure what happened in real life to explain a person's behavior. People keep secrets. Nobody reads like an open book, except in a book.

With a fictional character, "you know what he went through," Langley says. "You know all the details." And a make-believe character doesn't object to open speculation about his state of mind.

To consider all that zombies have to say about people, Langley enlisted this team of writers he calls "the league of extraordinary psychologists."

WALKING PAPERS

• Among the book's Arkansas contributors, psychologist Dana Klisanin of Russellville writes, "What Would You Do? Finding Meaning in Tragic Circumstances: A Bite-Sized Intro to Existential Psychology."

"The situation we find ourselves in has a great deal of power over us," she says. "By recognizing the power of a situation to change us, we already gain an element of power over it."

Not a zombie fan, Klisanin started watching The Walking Dead to understand the show's popularity. Her business is based on media studies at Evolutionary Guidance Media R&D Inc. in New York.

"I was struck by the existential angst the characters confront on a daily basis," she says, "and the difficult choices many of them have to make."

She points past the zombies to the late psychiatrist Viktor Frankl and his book Man's Search for Meaning (1946). Frankl survived the real-life horrors of Auschwitz and other Nazi concentration camps in World War II.

"When we are no longer able to change a situation," Frankl said, "we are challenged to change ourselves."

Everyone feels grief and despair at times, Klisanin says, but "we can still find meaning in life, even in the worst situations."

• John C. Blanchar and William Blake Erickson, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville doctoral candidates and researchers, contribute the book's chapter on "Apocalyptic Stress: Cause and Consequences of Stress at the End of the World."

Even without zombies to cope with, they write, most people have to confront such everyday tensions as money troubles and worries about the future. Zombies offer a way to understand how stress affects a person's mind.

"A little stress is beneficial and helps you carry out tasks optimally," Erickson says. Too much stress makes it hard to focus and interact well.

"I hope the chapter helps viewers feel a bit more empathy toward people in highly stressful situations, whether they're fictional or not," he says. "For example, too often when watching a show like The Walking Dead, I hear criticism of characters who don't notice that a walker is sneaking up on them. I also hear the more over-arching, 'Why don't they all get along and survive together?'

"In either case, the answer is simple: They're malnourished, haven't had a good night's sleep in ages, and are frightened for their lives every moment of every day."

The world's trouble spots "aren't too different from a post-apocalyptic landscape," he says. "Basic needs are hard to come by, and stress makes peace all the harder to achieve."

• "'It Should Have Been Me': Survivor's Guilt in The Walking Dead" is the subject for Mara Wood, a psychology doctoral student at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway.

"Zombies seem to encourage us to keep on our toes and be aware of the worst-case scenario," she says. "The Walking Dead allows for readers to explore grief and guilt in a safe environment."

• The book's other chapters include Langley's "Eros, Thanatos and an Armory of Defense Mechanisms: Sigmund Freud in the Land of the Dead," illustrated by his artist son, Nick; and Henderson State nursing and psychology graduate Katrina Hill's "Slash Hacks: Ways to Fool a Walker."

"Pop culture helps us better understand people who are different from us, as well as letting us identify with characters who are going through the same things we are," she says.

The dead can be distracted by flashlights, she writes, but "don't try dangling canned ham in front of a zombie's face."

Arkansas is famous for ham, but zombies don't care.

WALK ALL OVER

Zombies are everywhere these days.

• The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers zombie awareness posters and a comic book, Preparedness 101: Zombie Pandemic, to teach how to brace for the trouble.

Their slogan: "If you're ready for a zombie apocalypse, you're ready for any emergency." More information is available at cdc.gov/phpr/zombies.htm.

• The U.S. Army, as well, is out to fight zombies. The Army's how-to bulletin, Preventive Maintenance Monthly, warns that rust and corrosion spread like zombies as shown by comic-book zombies attacking a maintenance outfit.

The zombies groan, "RRRussst!"

• Max Brooks is the nation's "zombie laureate," according to The New York Times. Brooks wrote The Zombie Survival Guide (2003) and World War Z (2007), the basis of the Brad Pitt zombie movie (2013) and Z-sequel to come in 2017.

Brooks, the son of comedian Mel Brooks, told the Times, "I can't think of anything less funny than dying in a zombie attack."

WALK TO CLASS

Langley will teach a course on "Psychology of the Living Dead" during the spring semester at HSU.

"Psychology is about people. It's about why we do the things we do," he says. "I checked out my first book about psychology in the fourth grade, because I've always wanted to understand people."

He peeks under Darth Vader's helmet in his next book as editor, The Dark Side of the Mind: Star Wars Psychology, an October release from Sterling Publishing.

More books to come will take up the psychology of Star Trek and Game of Thrones for what the Klingons and the Lannisters have to say about the rest of us.

Meantime, Langley recommends a crowbar as the best implement to keep handy for swinging at zombies. In case of no zombies, he reasons, the tool is "practical for other things."

Style on 08/16/2015