DAMASCUS, Syria -- The Islamic State on Friday demolished a monastery founded more than 1,500 years ago in central Syria, near a town where the extremists abducted dozens of Christians earlier this month, activists and a priest said.

The destruction of the St. Elian Monastery near the city of Qaryatain comes days after the militant group publicly beheaded an 81-year-old antiquities scholar who had dedicated his life to studying and overseeing the ancient ruins in the Syrian city of Palmyra.

The developments have stoked concerns that the Islamic State may be accelerating its campaign to destroy and loot non-Islamic and pre-Islamic heritage sites inside the vast swaths of Iraq and Syria now controlled by the militant group.

"I think we are worried about almost all the heritage sites in Syria. Nothing is safe," said Irina Bokova, director general of UNESCO, adding that the Islamic State's "view on culture and heritage is just the opposite of what UNESCO stands for."

The extremist group, which captured the Qaryatain area in early August, posted photos on social media Friday showing bulldozers destroying the St. Elian Monastery.

A Christian clergyman said in Damascus that militants also wrecked a church inside the monastery that dates back to the fifth century. He spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals from the militants. The Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, which tracks Syria's conflict, also reported the destruction of the monastery.

A Qaryatain resident who recently fled to Damascus called on the United Nations to protect Christians as well as ancient Christian sites in Syria.

The man, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear his relatives still in Qaryatain might be harmed, said militants leveled the shrine and removed the church bells.

Osama Edward, the director of the Christian Assyrian Human Rights Network, said government shelling of the area had already damaged the monastery over the past two weeks before the extremist fighters destroyed it.

"Daesh continued the destruction of the monastery," said Edward, using an Arabic acronym for the Islamic State. He said the monastery was founded in 432.

A Catholic priest, the Rev. Jacques Mourad, who had lived at the monastery, was kidnapped in May and remains missing. Edward said Mourad sheltered both Muslim and Christian Syrians fleeing the fighting elsewhere in Homs province.

Activists said that shortly after capturing Qaryatain, the Islamic State abducted 230 residents, including dozens of Christians. Activists said some Christians were released, though the fate of the others is still unknown.

In February, the Islamic State kidnapped more than 220 Assyrian Christians after overrunning several farming communities on the southern bank of the Khabur River in the northeastern province of Hassakeh. Only a few have been released and the fate of the others remains unknown.

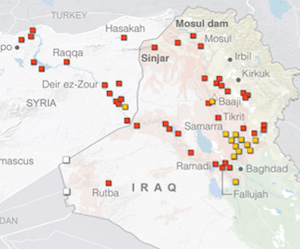

Since capturing about a third of Syria and Iraq last year, Islamic State fighters have destroyed mosques, churches and archaeological sites, causing extensive damage to the ancient cities of Nimrud, Hatra and Dura Europos.

Islamic State fighters overran the historic town of Palmyra in May. On Tuesday, famed Palmyra expert Khaled al-Asaad was publicly beheaded by Islamic State militants, his bloodied body hung on a pole in a main square, according to witnesses and relatives.

Antiquities officials said they believed militants had interrogated al-Asaad, a longtime director of the site, trying to get him to divulge where authorities had hidden treasures secreted out of Palmyra before the extremists seized the ruins.

The killing stunned Syria's archaeological community and underscored fears the extremists will destroy or loot the 2,000-year-old Roman-era city on the edge of a modern town of the same name, as they have other major archaeological sites.

Al-Asaad was known in the archaeological community as "Mr. Palmyra" for his decades of dedication to the site. Bokova described him as "a man who stood for more than 50 years behind Palmyra's research, a man who inscribed Palmyra on the world heritage list in the '80s, who dedicated his life to research."

She recalled first visiting Palmyra with al-Asaad as her guide: "He introduced me to this beautiful Venice of the desert, as it was called. We walked through the colonnades, more than a kilometer of beautiful colonnades."

Now she fears that Palmyra may suffer the same fate as other heritage sites that have fallen under Islamic State control. Archaeological experts have speculated that the Islamic State has, in the past, used the destruction of heritage sites to cover for the lucrative looting and selling of archaeological treasures.

"We know that some of the destruction has started," in Palmyra, Bokova said. Recent satellite images have revealed, "a terrible network of literally holes dug into the lands around Palmyra and inside, for illicit excavations and then eventually trafficking and looting," she said.

Information for this article was contributed by Bassem Mroue and Maamoun Youssef of The Associated Press.

A Section on 08/22/2015