The story below about hot-car deaths was originally published August 30, 2015.

Margette Staten knew something was wrong when she reached her husband's gray Ford Focus on a sweltering summer afternoon. She started screaming for help.

Her 2-year-old great-grandson, Joniah Chronister, was strapped into a pink-cushioned car seat in the car in a Springdale Wal-Mart parking lot. It was 4:39 p.m. on Aug. 3, 2012.

The child's great-grandfather, William Staten, soon arrived, grabbed the pale, unresponsive child, and rushed into the Wal-Mart for help. A witness in the parking lot called 911.

During the confusion of radio traffic, a dispatcher called the National Weather Service. The outside temperature was 102 degrees. The heat index -- a measure of how hot it feels when humidity is factored in with air temperature -- was 104 degrees.

Police and firefighters arrived within minutes and worked to resuscitate Joniah, who was taken to Northwest Medical Center in Springdale. He died at 5:21 p.m.

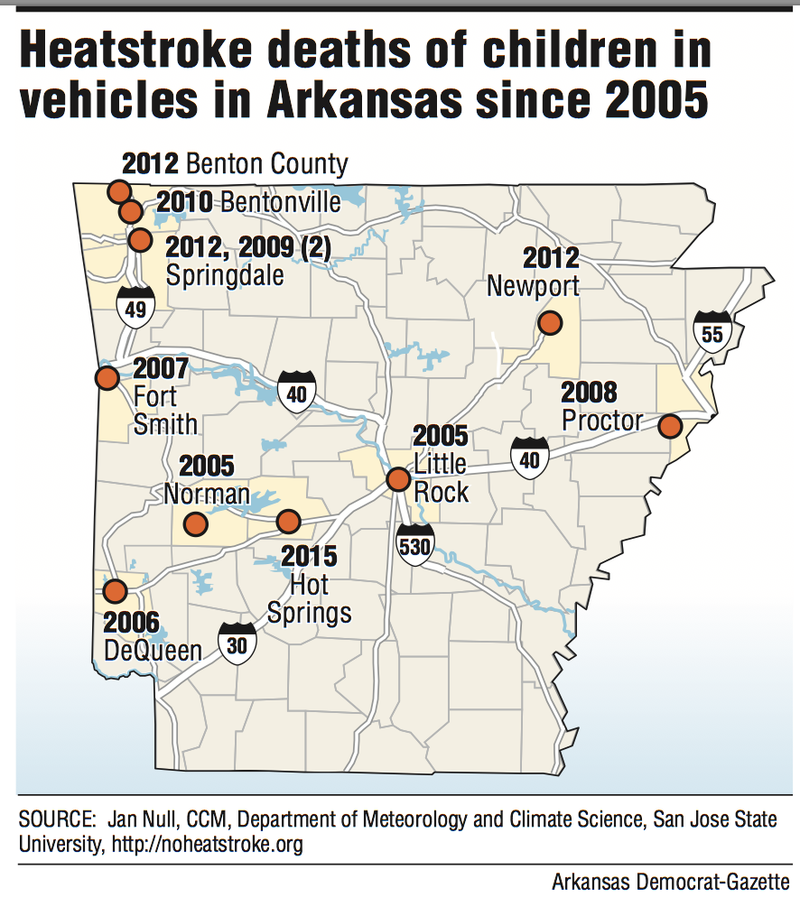

Joniah was one of at least 12 Arkansas children who since 2005 have died of heatstroke after being left in vehicles, said Jan Null, a meteorologist and lecturer at California's San Jose State University. Null tracks such data.

The Statens are the most recent people prosecuted in Arkansas for the heatstroke death of a child left in a vehicle. They pleaded guilty to misdemeanor negligent homicide in December 2012 and were sentenced to 60 days in the Washington County jail and fined $2,500 each.

"We still look for answers," Margette Staten said. "And there's no way that a person could actually explain it all except that it is an accident.

"We have no excuse for it. Our story has never changed. It can happen to anybody."

When Joniah arrived at the emergency room, his core temperature was 108 degrees. Twenty minutes later -- when all medical treatment was stopped -- his core temperature was 104 degrees.

The Statens told police they were taking Joniah to Wal-Mart and that he fell asleep on the way there. They forgot he was in the car. The couple said they went into the store. About 45 minutes later, Margette Staten realized that Joniah was still in the Focus. That's when she went out to get him.

A review of surveillance tape revealed that the Statens arrived at the Wal-Mart at 2:34 p.m., a police report said. The child had been alone in the car for two hours and five minutes by the time he was found.

"I wish I could forget about what did happen, even though I don't forget about it because it's the first thing in my mind constantly," said Margette Staten, 64. She and her 54-year-old husband still live in Springdale.

"It was an accident," she said. "I try to forget it, but ... it's a nightmare that stays with us."

Whether to prosecute

Since 1998, at least 653 children nationwide have died of heatstroke after being left in vehicles, Null said. His statistics show that roughly 73 percent of the children are age 2 or younger.

Most of the deaths are in June, July and August, but they occur in every month except January.

"It doesn't have to be a 90-degree day," he said. "About 11 percent of the cases happen on days less than 80 degrees."

On July 24, Thomas Naramore, the 1-year-old son of Garland County Circuit Judge Wade Naramore, died in Hot Springs as the result of "excessive heat" after being left unattended in a hot car for an unknown amount of time, a preliminary investigation showed.

Officers arrived at Fairoaks Place and James Street at 3:13 p.m. that day, after the judge called 911, according to a Hot Springs Police Department report.

The high temperature in Hot Springs that day was 101 degrees shortly before 5 p.m., according to National Weather Service records.

A phone number for Naramore was not listed, and the phone for the Naramores' law firm has been disconnected.

Scott Ellington, the 2nd Judicial District prosecuting attorney, has been appointed as a special prosecutor in Thomas' case. Ellington said Friday that his office is still investigating it.

In such cases, whether to prosecute the children's caregivers depends on a number of factors, said Jennifer Collins, dean of the Dedman School of Law at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Collins said she began studying these kinds of cases after a Virginia father was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter for leaving his youngest child strapped in a car seat for seven hours in May 2002.

While Collins was an assistant professor of law at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., she published a paper on 123 heatstroke cases between 1998 and 2003 involving 128 children.

During her study, Collins found information on charges in 111 of the cases, with at least 70 -- or 63 percent -- being prosecuted. Mothers were prosecuted about 59 percent of the time; fathers were prosecuted about 46 percent of the time.

"In my research, I found that parents were ... prosecuted about half the time," she said. "Mothers tended to be prosecuted more often than fathers. Unrelated caregivers -- baby sitter, nanny or day-care provider -- were almost always prosecuted."

Collins said she believes mothers were prosecuted more often than fathers because, "I think we tend, in general, to hold mothers to a higher standard of parenting than we do fathers."

"If you knowingly left the child in the car, not intending to kill the child but thinking they would be fine ... parents were always prosecuted in that situation," Collins said. "The other way parents are always prosecuted was if drugs or alcohol were involved."

Sentences in cases involving relatives ranged from probation to life in prison, Collins wrote.

One pattern in the study "suggested low-income individuals were much more frequently prosecuted than sort of the high-end income, white-collar professionals," Collins said.

"Parents working in blue collar professions or who were unemployed were four times more likely to be prosecuted than parents from wealthier socioeconomic groups," she wrote.

An Arkansas Democrat-Gazette review of fully adjudicated cases in Arkansas shows that of heatstroke deaths involving 11 children left in vehicles since 2005, there were five convictions: four on misdemeanor charges and one on a felony charge of negligent homicide.

In the negligent homicide case, the parents were given suspended sentences of one year in jail.

One of the misdemeanor convictions involved the 2009 deaths of two children, who were found unconscious in a car trunk in Springdale.

No charges were filed in four of the cases.

One case involved a misdemeanor negligent homicide charge that was later dropped.

"I think prosecutors have an ethical obligation not to pursue cases ... that are unlikely to result in a guilty verdict," Collins said. "These are terribly difficult, painful cases."

Temperature tests

At least 16 children have died nationwide of heatstroke this year after being left in vehicles, Null said.

He began tracking data on such cases after the death of a San Francisco Bay Area child in 2001. Media representatives called him, wanting to know how hot that vehicle could have gotten, and Null found that there were "no good data."

In 2005, he published a study in the Pediatrics journal with two Stanford University doctors evaluating temperature increases in enclosed vehicles.

For the study, temperatures were taken inside a dark sedan on 16 clear, sunny days, when the outside temperatures were between 72 degrees and 96 degrees. The study found that the temperature inside the car rose about 40 degrees within an hour's time, with 80 percent of that rise occurring in the first 30 minutes.

The temperature inside the car rose 19 degrees in the first 10 minutes.

"The rate of rise is very rapid," Null said. "Car color is not a big factor. It's the color of the interior of the car."

Cracking the windows doesn't help much, Null said. Cracked windows dropped the temperature by only a couple of degrees, he said. "Instead of 123 degrees, it will be 121 or 120 degrees."

After Joniah was taken to the hospital on Aug. 3, 2012, two Springdale police detectives and a deputy coroner took readings of the temperature inside the car about 6:15 p.m. One detective sat inside with an infrared thermometer. After five minutes, he got out, saying the temperature was around 130 degrees. Sweating profusely, he said he could no longer safely continue the testing, the police report said.

There's "no good information on how long" such temperatures take to become catastrophic for children and adults, said Dr. Mary Aitken, professor of pediatrics at UAMS Medical Center and medical director at the Injury Prevention Center at Arkansas Children's Hospital in Little Rock.

Children are more susceptible to the heat because they are physiologically immature, Aitken said. Their respiratory and circulatory systems are not as efficient. They absorb heat more quickly and can't sweat as efficiently as adults do to cool off.

"As soon as they get hot, they would be uncomfortable," Aitken said. "The progression is from just discomfort to thirst and sweating to loss of consciousness and death. That's the general arc.

"You sweat and pant, and there are a lot of different ways you can cool yourself down. But after a while, the body's capacity to do that is limited. If you don't get out of the environment, your temperature will rise. [Children] don't have as much to heat up, so they get hotter."

Heatstroke can occur once the body's core temperature rises to 104 degrees. According to an Arkansas Children's Hospital news resource, "If a child's core temperature reaches 107 degrees, convulsions, brain damage and death can occur."

State Crime Laboratory Executive Director Kermit Channell said the state's medical examiners don't keep track of the number of heatstroke deaths involving children left in vehicles, but the Naramore case is the only one his laboratory is investigating this year.

Channell said if "there is a heat-related death somewhere Arkansas, it doesn't necessarily mean that the county coroner will send it to the Crime Lab."

"It's up to them to decide whether or not they want an autopsy," he said.

But before the medical examination or legal process even starts, many outsiders rush to judgment, said Janette Fennell, president and founder of KidsAndCars.org. The national organization is dedicated to keeping children safe around vehicles.

"People really have this problem with trying to figure out how a child could ever be left alone in a vehicle," she said.

"The point we try to get across is the No. 1 mistake [people] can make is thinking that this can't happen to them. If they really feel as though they are immune, they are not going to put those little safety steps into place. That's a huge mistake."

Numerous factors might be in play when a child is unknowingly left alone in a vehicle, Fennell said, including sleep deprivation, stress, hormone changes and new routines, especially involving day care changes.

Her organization's advice is simple: Look before you lock. Open the back door of the vehicle when you park. And never knowingly leave a child in a vehicle.

"What we need people to understand is that it's not a lack of love in these cases," Fennell said. "It's definitely when your memory lets you down. That's a hard one for people to understand, but the biggest mistake that people can and do make is thinking it can't happen to them."

During his decade of collecting data, Null has read thousands of media reports about such cases.

"This could happen to anyone," he said. "Everyone says, 'I could never forget. I'm a responsible person. I'm a principal. I'm a hospital administrator. I'm a lawyer. I'm a dentist.' And it's happened to all of them, too."

State Desk on 08/30/2015