Working late in a tiny Arkansas lab, Susan Wilde found herself alone with a killer.

It startled her. She jumped, let out a yelp and took off down a hall. Wilde wasn't running for her life; she was amazed by a discovery. She had uncovered a bacteria, one with a powerful toxin that attacked waterfowl, hiding on the underside of an aquatic leaf that grows nearly everywhere in the United States.

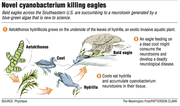

After 20 years of testing determined that the bacteria had never before been recorded and that the brain lesions it causes had never been found before that night in 1994, Wilde recently gave her discovery a name: Aetokthonos hydrillicola. The Greek word means "eagle killer" for its ability to quickly kill the birds of prey.

It's the latest threat to a raptor that is starting to flourish after being removed from the endangered species list.

Across the South, near reservoirs full of invasive plants from Asia called hydrilla, eagles have been stricken by this bacteria, which goes straight to their brains. Eagles prey on American coots, which dine almost exclusively on hydrilla.

Before now, reservoirs that serve up a buffet of this plant were considered beneficial because they helped fuel the annual migration of coots from Canada to Florida and beyond, while also feeding eagles. But now the reservoirs are "death traps," said Wilde, an assistant professor at the University of Georgia whose study of the topic was recently published in the journal Phytotaxa.

In Arkansas, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina and North Carolina, coots, shorebirds, ducks and eagles are dying by the dozens from the incurable lesions.

"We're attracting them to places where they're going to die, and that's not a good thing," Wilde said.

Eagles get top billing in the study because they're the national symbol, arguably the most-recognized animal in America. But the bacteria and its toxin hits coots harder.

The migration of coots is a spectacle that bird-watchers flock to man-made reservoirs to see. Five thousand can descend at once on a single lake, noisy, splashing, feeding.

The only way to save the animals is to spend millions to eradicate a plant that was introduced to the United States in Florida about 60 years ago. It now grows in virtually every body of fresh water, from the Southeast to California and Washington. It grows prolifically in the Chesapeake Bay region, which is full of bald eagles and visiting coots, a dark, plump, ducklike bird that has a bright orange dot for an eye.

Bald eagles were removed from the federal endangered species list only seven years ago. They nearly went extinct when their habitat was clear-cut in the past century, their prey (such as ducks) was overhunted and a pesticide caused them to lay eggs with shells so thin that their chicks couldn't survive. In 1978, they were listed as endangered in all but five states on the U.S. mainland, and in those five, they were listed as threatened.

Wilde and Brigette Haram, a doctoral student at the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources where Wilde teaches, conducted lab trials on chickens and mallard ducks to better understand the toxin and studied other disoriented and sick birds that were carried in.

"We haven't seen a species that's immune," Wilde said.

A hopeful observation is that many coots and eagles fly into reservoirs and lakes in the five affected states and fly away unharmed. Seemingly, that is. They could easily fly off and die elsewhere. "We don't know why some birds, within a week of arriving, die. But others come back the next year, conceivably," Wilde said.

The study's co-authors include Jeffrey Johansen of John Carroll University, Dayton Wilde and Peng Jiang of the University of Georgia department of horticulture, and former Warnell student Bradley Bartelme, now at EnviroScience.

Haram isn't a co-author, but she's trying to track the killer wherever it lives. So far, she's found it only as far north as North Carolina. Tests in Virginia and New York were negative. She hasn't tested in the Chesapeake Bay area, but it's on her to-do list.

Wilde first came across the bacteria in 1994. It was a master of disguise, taking on the same hue as the slim hydrilla leaf. She had been searching for it for days until she decided to shine light on the subject.

"The pigment shows up. It looks pretty. It just looks kind of scary and bright and red," she said.

SundayMonday on 02/22/2015