LONDON -- The man in the black balaclava who seems to have beheaded several foreign hostages in Islamic State videos has been identified by British security services as Mohammed Emwazi, a British citizen from London.

RELATED ARTICLE

http://www.arkansas…">Militants kidnap more Christians

Often referred to as "Jihadi John," he is said to have been born in Kuwait and traveled to Syria in 2012. His name was first published Thursday on the website of The Washington Post.

The story was confirmed by a senior British security official who said the British government had identified Emwazi some time ago but had not disclosed his name for operational reasons. The identification also was confirmed in Washington by a senior U.S. military intelligence official.

Emwazi, 26, grew up in West London and graduated from the University of Westminster with a degree in computer programming.

He first showed up in Islamic State videos in August, when he delivered threats against the West and appeared to behead the American journalist James Foley. The actual execution was not included in the video.

What was believed to be the same man was seen in the videos of the beheadings of a second American journalist, Steven Sotloff; a British aid worker, David Cawthorne Haines; a British taxi driver, Alan Henning; and an American aid worker, Peter Kassig.

Last month, he appeared in a video with Japanese hostages Haruna Yukawa and Kenji Goto shortly before they were killed.

Information is still vague about Emwazi, with Britain officially refusing to confirm that he is indeed "Jihadi John," because of what are described as continuing operations.

But Emwazi appears in 2011 court documents, obtained by the BBC, as a member of a network of extremists who funneled funds, equipment and recruits "from the United Kingdom to Somalia to undertake terrorism-related activity."

Emwazi is alleged to be part of a group from West and North London, sometimes known as "the North London Boys," with links to Somalia's al-Shabab militants and organized by an individual whose name was redacted who had returned to London in February 2007.

Emwazi apparently was set on the path to radicalization after being detained by authorities after a flight with friends to Tanzania in 2009 for a safari after graduation. He was accused by British intelligence officers of trying to make his way to Somalia to join al-Shabab.

Friends told the Post that Emwazi and two others -- a German convert to Islam named Omar and another man, Abu Talib -- never made it to the safari. On landing in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in May 2009, they were detained by the police and held overnight before eventually being deported, they said.

Later, Emwazi said an officer from MI5, Britain's domestic security agency, tried to recruit him.

Asim Qureshi, a research director at CAGE, a British advocacy organization opposed to what it calls the "war on terror," met with Emwazi in the fall of 2009.

"Mohammed was quite incensed by his treatment, that he had been very unfairly treated," Qureshi told the Post.

But Qureshi repeated in a statement Thursday that he could not identify Jihadi John as Emwazi with complete certainty. Qureshi said two years of communications with Emwazi highlighted "interference by the UK security agencies as he sought to find redress within the system."

Emwazi moved to Kuwait, his birthplace, working for a computer company, and he returned to London at least twice, Qureshi said. British counterterrorism officials detained Emwazi in June 2010, fingerprinting him and searching his belongings.

In July of that year, Qureshi said, Emwazi was not allowed to return to Kuwait, which had apparently refused to renew his visa and blamed it on the British government.

"I had a job waiting for me and marriage to get started," he wrote in a 2010 email to Qureshi. "But now I feel like a prisoner, only not in a cage, in London. A person imprisoned & controlled by security service men, stopping me from living my new life in my birthplace & my country, Kuwait."

In his statement, Qureshi said of Emwazi, "He desperately wanted to use the system to change his situation, but the system ultimately rejected him."

Qureshi said he had last heard from Emwazi in January 2012.

But Shashank Joshi, a senior research fellow at Royal United Services Institute, a British research institution, said there were doubts about CAGE's "crude and simplistic" narrative of radicalization because of police mistreatment.

He pointed out that there was evidence of Emwazi's involvement with Somalia before he was ever detained, and long before the Syrian civil war and the rise of the Islamic State.

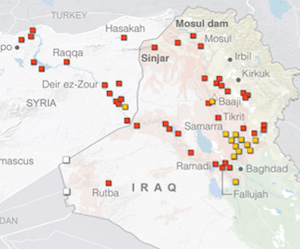

British officials estimate that there are at least 500 homegrown militants fighting in Syria and Iraq, some of whom have returned to Britain.

Information for this article was contributed by Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura of The New York Times.

A Section on 02/27/2015