"I'm gonna wake up with another funny haircut and more tattoos."

-- Kit, the roadie for X in The Decline of Western Civilization

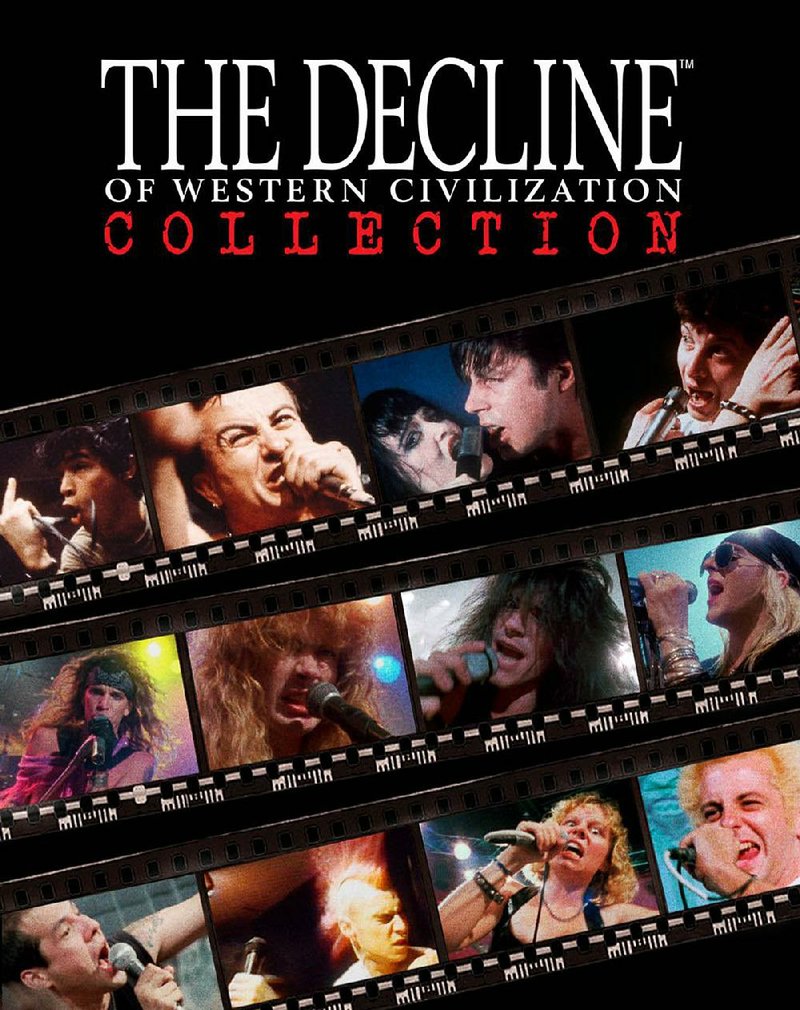

To talk about Penelope Spheeris' three The Decline of Western Civilization documentaries, which are finally being officially released on home video (Shout Factory, $59.98 Blu-ray; $39.98 DVD) June 30, it's interesting to go back to Oswald Spengler, the German intellectual who wrote and published The Decline of the West in the years after World War I.

Spengler believed that history should be viewed not as a series of temporal "epochs," but as a series of cultures that evolved and thrived like organisms: They were born, evolved into "civilizations" after they matured and their critical impulses overcame their creative imperatives and they inevitably died. Spengler identified eight high cultures: Babylonian, Egyptian, Chinese, Indian, Mayan/Aztec, Classical (Greek/Roman), Arabian and finally Western, by which he meant European-American.

Each of these cultures, Spengler observed, had a life span of about a thousand years. Western civilization, he argued, was coming to an end. (Not a cataclysmic end, more of a slow sun-setting.) This gave some comfort to the downtrodden German people, caught in hyperinflation and oppressed by the Treaty of Versailles. Some, especially Joseph Goebbels, were encouraged by Spengler's writing. They thought they knew exactly who would become the rising Caesar Spengler referred to in his book.

Yet while he voted for Hitler in 1932 and was initially optimistic about the rise of the Nazis, Spengler was not really a fan of the vulgar little Fuhrer with his dreams of a 1,000-year Reich. He thought the Nazi belief in racial purity was "grotesque" and suggested Hitler was what the Texans call "all hat and no cattle." In 1934, he published The Hour of Decision which criticized some tenets of National Socialism but didn't mention Hitler at all. The Nazis responded by censoring Spengler and banning his books. If he had not died of a heart attack in 1936 -- a few months after prophesying that the Third Reich wouldn't last another decade -- he probably would have wound up murdered or in a concentration camp.

Now I don't know if Spheeris, who in some circles is probably better known as the director of Wayne's World, The Beverly Hillbillies or the Chris Farley film Black Sheep than for her Western Civ docs, had Spengler in mind when she set out to document the Los Angeles punk rock scene in 1979. But one of her chief subjects, Darby Crash, lead singer of the Germs, was a fan of Spengler and Hitler. And Charles Manson too.

There's a scene in the film where Crash and his friend Michelle Baer (who was briefly in the Germs and who would go on to co-write a feature film about Crash's short life, 2007's What We Do Is Secret) talk about a morbid discovery she made while her parents were on vacation. When she took the garbage out one night she discovered the body of a house painter in her backyard. He had apparently died of a heart attack and fallen off a ladder earlier in the day.

"I lied down next to him and we all got around him and took a bunch of pictures, like family pictures ... it was really funny actually, and the paramedics came and they were joking with us and the coroner came ...."

"Instead of 'John Doe' they put down 'Jose Doe' because it was a wetback," Crash interjects.

"Didn't you feel bad that the guy was dead?" we hear an off-camera Spheeris ask.

"Not at all," Baer replies. "Because I hate painters."

Throughout this conversation, Crash has been making breakfast. When he accidentally breaks the yolk of the egg he's been frying, he looks genuinely upset. Almost as if he could cry.

...

Crash, born Jan Paul Beahm, is one of those obscure legends, kind of an American analogue to Ian Curtis, the Joy Division singer who was 23 years old when he hanged himself in May 1980. Crash was 22 when he intentionally overdosed on heroin on Dec. 7, 1980 -- the day before John Lennon was murdered and eight months before The Decline of Western Civilization was released. The poster and the cover of the soundtrack album featured a photograph of Crash lying on stage, his face and bare chest scrawled with permanent marker, his eyes closed, a Teutonic Iron Cross around his neck.

In a way, the image is a perfect symbol for the nihilistic hardcore punk rock that developed in Los Angeles -- an angry and unwholesome scene that grew parallel to the more intellectual New York scene (early on, both were influenced by British punk bands like the Sex Pistols but grew increasingly provincial; when Crash returned from a trip to England a few months before his death obsessed with Adam Ant, foppishly dressed and wearing war paint, he was roundly ridiculed). This was where mosh pits first appeared, where angry kids could take out their aggression on their friends.

"Like when I go to concerts," a young skinhead named Eugene tells Spheeris, "my friends get beat up by my friends ... they're not beating up the right people."

A lot of the music -- from bands like Black Flag, X, Alice Bag Band, Circle Jerks, Catholic Discipline and Fear -- captured in The Decline of Western Civilization feels like assaultive noise, inexpertly applied. If you think you hear three chords, you might be overthinking.

When they were first getting the band that would become the Germs started, Crash and his longtime friend Pat Smear (Georg Albert Ruthenberg) advertised for "untalented" girls to fill out the rhythm section. (One of those who applied but never played with the band because of a bout of mononucleosis was future Go-Go Belinda Carlisle.) If there was any intellectual undercurrent to the scene at all, it was subsumed by the unregenerate pose of disaffected youth with no hope and no future. Some of them would grow out of that -- Smear is now a middle-aged rock star playing alongside Dave Grohl in Foo Fighters. Some, like Crash, never got the chance.

While it's easy to misperceive The Decline of Western Civilization as a kind of concert film with interviews, it's the interviews that are the most fascinating part. It's the aforementioned Eugene who sets the tone as he talks to the camera in a room unadorned but for a naked light bulb suspended over his right shoulder. He glares into the camera and cuts through the grainy monochrome fog.

"That's stupid -- 'punk rock.' I just think of it as rock 'n' roll 'cause that's what it is," he says. "I like it 'cause it's like something new and it's just, like, it's raw again and it's for real. And it's fun. ... There's no rock stars now."

But aren't there? Spheeris consciously divides her movie between static black-and-white interviews with nobodies like Eugene while the musicians perform and comment in over-saturated color. Crash certainly comes across as a rock star -- a pocket David Bowie -- though when the interviews were conducted in 1979 and 1980 he was already running out of time.

The Germs had been the biggest punk band in Los Angeles in 1977; they were eagerly adopted and Crash developed a following of acolytes -- "Circle One," he called them -- who adored him with a kind of Manson Family-like ardor. (You could tell them by the round scars, caused by cigarette burns, on their wrists. It was higher status to have been burned in by Crash.)

But by the time Spheeris showed up with her cameras, the Germs were blacklisted from most Los Angeles clubs. Club owners couldn't risk a riot by booking them. So in the film they perform on a sound stage Spheeris rented for the purpose. They'd rarely perform after the film and their final show -- a reunion concert -- was engineered by Crash so he would have enough money to buy enough heroin to kill himself.

In a way that feels like a grimly perfect way to close a rock 'n' roll career; you get a couple of years of making music for kids, then it's over -- the second act is a plane crash or an overdose. Crash didn't display a lot of intellectual rigor -- he was a wordy lyricist and a declamatory singer who aptly described himself as a "lexicon devil with a battered brain" on the Germ's first single. But just because he'd read (or claimed to have read) Spengler, Nietzsche, L. Ron Hubbard and Mein Kampf doesn't mean he'd gotten anything from them other than a bad attitude.

"One day you'll pray to me," he used to say -- he played at creating his own religion. (He'd attended a school that applied Scientology methods.) It didn't take; he stayed dead. He's very nearly forgotten.

...

In their own way, the second and third films in the series have their merits -- The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years might best be received as a kind of comedy, a kind of real-life Spinal Tap as Spheeris documents the glam metal scene, interviewing a risibly louche Paul Stanley of KISS in bed with four or five (or more) women and -- in what may be a homage to her interview with Crash -- Ozzy Osbourne cooking breakfast.

The final film, 1998's The Decline of Western Civilization Part III, chronicles the gutter-punk lifestyle of homeless teenagers in Los Angeles, interspersing interviews with street kids and performances by hardcore punk bands Final Conflict, The Resistance and Litmus Green and libertarian socialist political punks Naked Aggression.

In addition to the three original films, which have been given a 2K high-definition restoration under Spheeris' supervision, the Shout! Factory boxed set also includes a fourth disc of performances that didn't make it into the theatrical releases of the films, a 40-page book and extended interviews. In addition to commentary tracks by Spheeris on the three films, The Decline of Western Civilization features -- for whatever it's worth -- a new commentary track by Smear's current bandmate Grohl.

Taken together, the three films serve as an alternate history of late 20th-century Los Angeles, not all that far removed from the nihilistic vision of James Ellroy's quasi-fictional L.A. Quartet. But while Ellroy's crooked cops and bent criminals were mostly imagined monsters, Spheeris' disenfranchised kids were real people, scuffling on the hopeless margins of America's most provisional city.

While there's plenty of grim humor (and the filmmaker retains a rigorous detachment from her subjects) in The Decline movies, they do feel like a transmission from the end of history, like the last hot breath of a decadent culture. Somewhere Spengler mumbles: I told you so.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 06/21/2015