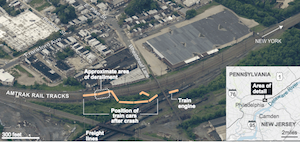

PHILADELPHIA -- The Amtrak train that crashed in Philadelphia, killing at least seven people, was traveling at 106 mph before it ran off the rails along a sharp curve where the speed limit drops to 50 mph, federal investigators said Wednesday.

The engineer applied the emergency brakes moments before the crash but managed to slow the train to only 102 mph by the time the locomotive's black box stopped recording data, said Robert Sumwalt of the National Transportation Safety Board. The speed limit just before the bend is 80 mph, he said.

The engineer, whose name was not released, refused to give a statement to law enforcement officials and left a police precinct with a lawyer, police said. Sumwalt said federal accident investigators want to talk to him but will give him a day or two to recover from the shock of the accident.

"There's no way in the world that he should have been going that fast into the curve," Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter told CNN. "Clearly he was reckless and irresponsible in his actions. I don't know what was going on with him, I don't know what was going on in the cab, but there's really no excuse that could be offered."

More than 200 people aboard the Washington-to-New York train were injured in the wreck, which happened in a decayed industrial neighborhood not far from the Delaware River just before 9:30 p.m. Tuesday. Passengers crawled out the windows of the torn and toppled rail cars in the darkness and emerged dazed and bloody, many of them with broken bones and burns.

It was the nation's deadliest train accident in nearly seven years.

Amtrak suspended all service until further notice along the Philadelphia-to-New York stretch of the nation's busiest rail corridor as investigators examined the wreckage and the tracks and gathered other evidence. The shutdown forced thousands of commuters to find other ways to reach their destinations.

Among the dead in Tuesday's crash were award-winning Associated Press video software architect Jim Gaines, a 48-year-old father of two; Justin Zemser, a 20-year-old Naval Academy midshipman from New York City; Abid Gilani, a senior vice president in Wells Fargo's commercial real estate division in New York; and Rachel Jacobs, who was commuting home to New York from her new job as CEO of the Philadelphia educational software startup ApprenNet, officials said.

At least 10 people remained hospitalized in critical condition Wednesday.

Nutter said some people remained unaccounted for but cautioned that some passengers listed on the Amtrak manifest might not have boarded the train, while others might not have checked in with authorities after the crash.

"We will not cease our efforts until we go through every vehicle," the mayor said in the afternoon. He said rescuers expanded the search area and were using dogs to look for victims in case anyone was thrown from the wreckage.

The National Transportation Safety Board finding about the train's speed led some to question why Amtrak had not installed along that section of track Positive Train Control, a technology that uses GPS, wireless radio and computers to prevent trains from going over the speed limit. Most of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor is equipped with the technology.

"Based on what we know right now, we feel that had such a system been installed in this section of track, this accident would not have occurred," Sumwalt said.

The tight curve is not far from the site of one of the deadliest train wrecks in U.S. history: the 1943 derailment of the Congressional Limited, bound from Washington to New York. Seventy-nine people were killed.

Amtrak had inspected the stretch of track Tuesday, just hours before the accident, and found no defects, according to the Federal Railroad Administration. In addition to the data recorder, the train had a video camera in its front end that could yield clues to what happened, Sumwalt said.

The crash took place about 10 minutes after the train pulled out of Philadelphia's 30th Street Station with 238 passengers and five crew members listed aboard. The locomotive and all seven passenger cars hurtled off the track as the train made a left turn, Sumwalt said.

Jillian Jorgensen, 27, was seated in the second passenger car and said the train was going "fast enough for me to be worried" when it began to lurch to the right. Then the lights went out and Jorgensen was thrown from her seat.

She said she "flew across the train" and landed under some seats that had apparently broken loose from the floor.

Jorgensen, a reporter for The New York Observer who lives in Jersey City, N.J., said she wriggled free as fellow passengers screamed. She saw one man lying still, his face covered in blood, and a woman with a broken leg.

Jorgensen climbed out an emergency exit window, and a firefighter helped her down a ladder to safety.

"It was terrifying and awful, and as it was happening it just did not feel like the kind of thing you could walk away from, so I feel very lucky," Jorgensen said in an email. "The scene in the car I was in was total disarray, and people were clearly in a great deal of pain."

Patrick Murphy, a former U.S. congressman from Pennsylvania, also was on the train.

"The guy next to me was unconscious [after the crash], so I just kind of picked him up and slapped him in the face and said 'Hey buddy, get up, get up,' and he came to," Murphy said.

Commuters in a bind

On Wednesday, the effect of the accident spread quickly from those directly involved in the crash to the thousands of commuters who rely on trains in the region.

The crash choked Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, which carries more than 750,000 passengers a day between eight states and the District of Columbia on Amtrak and eight commuter rail lines. Amtrak said it alone carried 11.6 million passengers through the Northeast Corridor in fiscal 2014, its highest ridership year yet.

In addition to the halt of service between New York and Philadelphia, Amtrak trains were operating on a modified schedule elsewhere. Service on local rail lines was affected because Amtrak shares the rails with several commuter lines.

Commuters on Wednesday were left scrambling to find alternative means of travel. Airline officials said shuttles between New York and Washington were overbooked. The lines at rental-car companies grew by the hour, and buses were packed to capacity.

With Amtrak service likely to be suspended for days, officials warned that the commuting headaches would probably worsen.

New Jersey Transit, Greyhound and Megabus were honoring Amtrak tickets Wednesday, but the buses were filling up quickly. Greyhound said it scheduled 16 more trips between New York, Philadelphia and Washington.

Sean Hughes, the director of corporate affairs for Megabus, said the bus company was working to add trips.

"We are working through logistics here to try and accommodate the unexpected demand in a timely fashion," Hughes said. "We are working to get additional trips today and also anticipating increased demand over the coming days and planning additional trips in advance."

The lines in Manhattan for Megabus trips to Philadelphia, Delaware, Baltimore and Washington stretched for blocks.

Nicholas Lopez said that when he had taken a bus to Philadelphia on Tuesday, he was one of only 10 passengers. On Wednesday, the trip was not going as smoothly.

"I had problems booking online because it got sold out," he said, "and now I'm worried I won't get a seat."

As more and more people turn to trains as an alternative to airports or overcrowded roadways, the infrastructure is increasingly strained, officials have said.

Joseph Boardman, the president and chief executive of Amtrak, said the situation was getting worse by the day in a report on the railroad's performance for fiscal 2014.

"As more and more people choose Amtrak for their travel needs, investments must be made in the tracks, tunnels, bridges and other infrastructure used by intercity passenger trains particularly on the Northeast Corridor and in Chicago," he said. "Otherwise, we face a future with increased infrastructure-related service disruptions and delays that will hurt local and regional economies and drive passengers away."

After Tuesday night's accident, it was clear how quickly and deeply a disruption of service could ripple through the region.

At New York's Penn Station, commuters found routine trips to Philadelphia or Washington abruptly canceled, their trusted link to meetings and conferences suddenly missing.

Many travelers were irritated that they had not been alerted to the problems by Amtrak earlier, arriving at Penn Station to hear a continuous announcement suggesting people try New Jersey Transit.

Others took it as a jarring reminder that they could not rely on public transportation to get them to their destinations safely.

Andrea Lynch, who was headed to Washington for work training, said her problems were unimportant compared to those of the people on the derailed train.

"For me, it's not really that big a deal," she said. "The big deal is we have a federal government that can't, for political reasons, invest in public transportation. It's infuriating."

Information for this article was contributed by Geoff Mulvihill, Maryclaire Dale, Michael R. Sisak, Josh Cornfield, Jack Gillum, Ted Bridis, Joan Lowy, Jessica Gresko, Karen Matthews, Scott Mayerowitz, Sarah Brumfield and Michael Rubinkam of The Associated Press; and by Mark Santora, Tatiana Schlossberg, Ben Mueller, Elizabeth Harris, John Surico, Jon Hurdle, Richard Perez-Pena, Jad Mouawad, Motoko Rich, Ashley Southall, Michael Shear, Emma G. Fitzsimmons and Dave Philipps of The New York Times.

A Section on 05/14/2015