Someone told me there were approximately 4,000 books of poetry published last year -- not including chapbooks and e-publications. I looked at, maybe, 50. I read more than a couple of pages in maybe 20. There were five or six that I considered writing about. No way can I pretend to have a handle on the contemporary poetry scene.

I read about 100 books last year. Most I finished, some I didn't. There were probably another 150 or so I read a little, or quite a bit, in -- books that I considered writing about, but discarded. So I don't really feel qualified to hold forth on anything like the state of literature. I just read books.

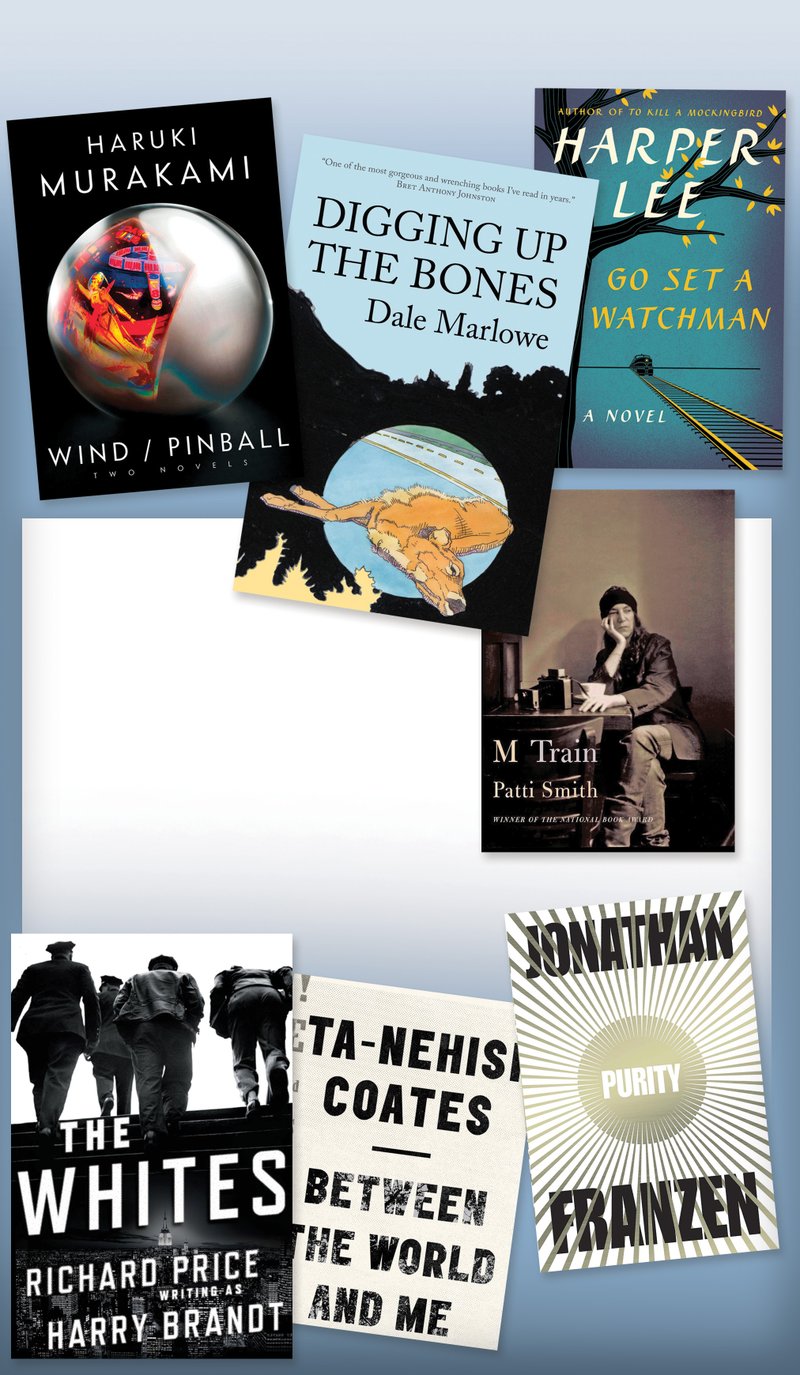

Mainly, I read a lot of what tends to be marketed as literary fiction. I am not so much about plot -- I much prefer Kevin Barry's audacious Beatlebone (Doubleday, $24.95) to Lee Child's most recent Jack Reacher book Make Me (Delacorte Press. $28.99), although I appreciate Child's insistence on pushing his tough guy trope in the direction of tenderness. Point is, while I love Beatlebone I'm not sure I admire Make Me less.

I'm a language guy. I like the way words knock together and spark, the little blooms of reception and recognition that can be set off in your head by the right rhythms and juxtapositions. Not crazy about the showier acrobats, the Tom Robbins school of cart-wheely sentence building (not to pick on Robbins, whose work I once devoured, but the author nailed the syndrome when he said his goal was "to write novels that are like a basketful of cherry tomatoes -- when you bite into a paragraph, you don't know which way the juice is going to squirt"). I find myself admiring the pyrotechnics for a while, but the dazzle fades.

So, you know: I didn't read everything and I have certain tastes. With that said, here are my notable books of 2015:

FICTION

- Digging Up the Bones by Dale Marlowe (Roundabout Press, $15.95) -- A brief suite of connected stories about cursed members of the meth trash Nash family, originally of Ebb Holler, Ky., that take place over the course of a few decades, from 1969 to 2003. In these stories we meet all manner of scarred and stunted folks, from would-be presidential assassins to disillusioned white supremacists. They are all fantastic creatures, yet they seem very much like people I have known, or might have known. Or might have been.

But more importantly than these characters or what happens to them is the author's voice: a ferocious, low-to-the-ground animal with yellow eyes that bites.

- Beatlebone -- Barry imagines a three-day trip the primal screaming John Lennon may have made to the island he owned off the west coast of Ireland in 1978. Barry gives us a Lennon we can recognize and believe in without reducing him to a series of tropes.

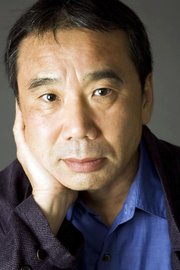

- Wind/Pinball, by Haruki Murakami (Knopf, $25.95) -- Murakami's first two books, 1979's Hear the Wind Sing and 1980's Pinball, 1973 were newly translated from Japanese and -- for the first time -- published with an English-speaking market in mind. (Earlier translations were aimed at Japanese readers learning English.) Both of these novellas have the indelible sense of detachment that permeates all of Murakami's fiction -- a deadpan dreaminess that fatalistically accepts all manner of remarkable goings-on.

While less inclined to flights of magical realism than Murakami's later work, these novellas engage Murakami's trademark themes of alienation, ennui and the transient nature of all things.

- The Cartel by Don Winslow (Knopf, $27.95) -- Hemingway believed readers could perceive a writer's authority even through simple, declarative prose. He thought that a sentence written by a writer who understood a subject somehow resounded truer in the mind of a reader than the same sentence written by someone who was faking it. I do not know whether I quite believe that, for I know people are all the time fooled by con men and moral imbeciles. But I perceive things beneath the surface of The Cartel -- a deep sadness and anger, a great stopped reservoir of outrage.

Winslow is a clean writer; his voice is uncluttered and calm. He's not the stylist his influence James Ellroy is, but he doesn't indulge in the literary pyrotechnics or self-aggrandizement of the lovable Demon Dog of American Crime Fiction. His story feels less like a product of the imagination than an exhaustively researched bit of journalism. Which it is -- a kind of true story set in the recognizable horror show of Mexico narco-terrorism. Winslow has introduced fictional characters into this world; he has changed names and details and muddled chronologies; but there's no doubt he's drawing from life.

- Purity by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, $28) -- I might join the debate on this divisive, intelligent book at some later point. Or I might not. But chances are you already have an opinion on Franzen, and this piece is running long.

- The Whites by Richard Price writing as Harry Brandt (Henry Holt, $28) -- The crime novel -- what the French call a policer -- has become a kind of obligatory exercise for the literary novelist with aspirations of making a living. Richard Price, transparently writing as "Harry Brandt" for reasons I don't particularly care about, has a good feel for the offhand grotesqueries of the work (late in the book a citizen is "shot" by his own lawn mower) and the novel is a wickedly quick read. And while you might be able to argue that The Whites is a little more plot-driven with more dialogue and slightly less character development than you'd find in some of Price's other novels, to me it feels like it was written by the same guy who wrote Clockers. And that's not a bad thing.

Price, who grew up in the Bronx and was a writer on HBO's series The Wire, is not just a programmatic storyteller. The best reason to read him isn't for the episodic storytelling, but the haunted language. An ex-athlete turned next of kin is "deep into his sixties but DNA-blessed with the physique of a lanky teenager ... his flat chest the color of a good camel hair coat. But his eyes were maraschinos, and his liquored breath was sweet enough to curl Billy's teeth."

7. The Blue Guitar by John Banville (Knopf, $25.95) -- Barely a story at all, the venerable Banville's latest comprises the musings of a failed painter, Oliver Otway Orme, who has retreated to his boyhood home in Ireland after blowing up his world via an affair with Polly, the wife of his best friend, watchmaker Marcus.

Unreliable, solipsistic and a generally dreadful fellow, Oliver perversely prides himself on his lifelong habit of thievery, the taking of things of little or (in the case of Polly) great consequence. The point is for the victim to feel the pain of loss, while never knowing who inflicted it, which stimulates in Oliver a transitory feeling of possession. Mainly he's a vile old codger, full of complaint and bile. He can be funny, but never redeemed.

- The Tsar of Love and Techno: Stories by Anthony Marra (Hogarth, $25) -- This minor miracle is a series of short stories, but they are so tightly interwoven that you'd be best served by approaching it as a novel. Read it sequentially and wait for the details to lock in place. Minor characters become important; hardly a word is wasted. It's an exquisite machine.

But it's more than that. Marra is a writer of uncommon power and precision, and this is an ambitious book that's even better than his heralded debut novel, 2013's A Constellation of Vital Phenomena.

- A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James (Riverhead, $28.95) -- I'm only a couple of chapters into the 2015 Man Booker Prize winner, a virtuoustic riot of tonal shifts and savage irony hung on a skeleton based on actual events, but so far I love it.

- The Visiting Privilege: New and Collected Stories by Joy Williams (Knopf, $30) -- A quiet master's career laid out as an unassailable argument for excellence. Of the 46 stories presented here, 13 are in book form for the first time.

Honorable mention: The Mourner's Bench by Sanderia Faye (University of Arkansas, $19.95); A Strangeness in My Mind: A Novel by Orhan Pamuk, (Knopf, $28.95); City on Fire by Garth Risk Hallberg (Knopf, $30).

Must be addressed: Not wanting to add to the hype, I purposefully didn't write about Go Set a Watchman, the alleged "new" novel from Harper Lee, in the newspaper last year, but I did consider it on the blood, dirt & angels blog. There I wrote that the novel was "an inchoate book that has been assembled to exploit the often morbid curiosity that has surrounded its author for years. It is a thing created to generate money rather than a work designed to illuminate and tease the mysteries of the human condition. And while most books are probably exactly that, I don't write about most books. There is too little time to devote much energy to the cynical machinations of capitalist main chancers." If you want to read the entire piece it's at tinyurl.com/gsvjkro.

NONFICTION

The problem of nonfiction is that I tend to read only those books I want to read -- I don't feel compelled to slog through important biographies of political figures and the like. I'm highly idiosyncratic about the nonfiction I read, passing over things I probably ought to pay attention to. I have been meaning to get around to Letters to Vera, the well-reviewed collection of Vladimir Nabokov's correspondence to his wife (Knopf, $40), edited and translated by Olga Voronina and Brian Boyd, but it's nearly 800 pages -- in favor of books about pop music and baseball. But here's a list anyway.

- Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink by Elvis Costello (Riverhead, $30) -- A raconteur remembers. You know how people say they hate for some books to end? Usually that's not really true. But I wish I could keep on reading this one. It's just my generation, I guess.

- Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life by Jonathan Bate (Harper, $40) -- Sadly, most of what most people think they know about one of the greatest writers of the 20th century might be encapsulated in the snide couplet: Sylvia Plath was good for a laugh/ But her husband Hughes was really bad news. But there was so much more.

- Schubert's Winter Journey by Ian Bostridge (Knopf, $29) -- A handsome, compact yet heavy volume of essays on Franz Schubert's song cycle Winterreise (Winter Journey) by the celebrated British tenor. Winterreise, a piece for voice and piano, was first published in 1828 and is a setting of 24 poems by Wilhelm Muller. Bostridge's essays are wonderfully discursive pieces that place the music in historical context and explore the nuances of performance.

- Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker by Thomas Kunkel (Random House, $30) -- "Unfortunately, I'm afraid all biographies and autobiographies are fiction," The New Yorker's Joseph Mitchell told literary critic Norman Sims in 1989. Maybe so, but Kunkel's book is a deeply interesting if intermittently frustrating attempt at explaining the enigmatic writer who went from being a prolific and especially graceful chronicler of uncelebrated lives to a cautionary tale. (For the last 32 years of his long career at The New Yorker, from 1964 until 1996, Mitchell failed to publish a single word.) This fact sadly obscures the quiet power of his work. Mitchell was especially adept at imbuing the denizens of low quarters with dignity no matter how bizarre they might initially appear.

- Days of Rage by Bryan Burroughs (Penguin Press, $29.95) -- I finally wrestled this thick (608 page), exhaustively researched account of the tumultuous and violent left-radical counterculture of the 1960s and '70s -- a time when it seemed actually possible that the world could fly apart, from my wife, Karen, who monopolized it for a couple of months, stopping every now and then to read me bits of what now seems an impossible history. We were closer to the maelstrom than we knew.

- Sinatra: The Chairman by James Kaplan (Doubleday, $35) -- The second, concluding volume of Kaplan's magisterial biography of one of America's greatest artists, a deeply flawed and complicated subject. It is especially good on the collaboration between Sinatra and Nelson Riddle.

- The Speechwriter by Barton Swaim (Simon & Schuster, $25) -- A strangely sweet memoir about his time on the staff of S.C. Gov. Mark Sanford, the infamous politician who disappeared for a week back in 2009, leaving his staff members to tell the world he was "hiking the Appalachian Trail" while he was actually holed up with his mistress in Argentina. But while that tabloid incident may well be the reason Simon & Schuster published the book, this isn't an inside baseball account of a scandal. Swaim is too generous and adept a writer for that. Although the governor in the book is an odd and parsimonious narcissist who is impossible to please, I ended up feeling empathy for him.

- M Train by Patti Smith (Knopf, $25) -- The expressionistic follow-up to Smith's National Book Award--winning memoir of New York in the '70s, Just Kids, M Train is a meditation on travel, loss and "stories."

9. Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates (Spiegel & Grau, $35) -- Uncommonly powerful, book-length essays written as a series of letters to the author's teenage son on the intractable American problem, the myth of race.

10. Street Poison: The Biography of Iceberg Slim by Justin Gifford (Doubleday, $26.95) -- The first biography of Robert Beck, aka Iceberg Slim, (1918-1992), the pimp-turned-writer who was arguably the father of Blaxploitation cinema and gangsta rap.

Honorable mention: Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention That Launched the Military-Industrial Complex by Michael Hiltzik (Simon & Schuster, $30); On the Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks (Knopf, $27.95); How Music Got Free by Stephen Witt (Viking, $27.95); Furiously Happy by Jenny Lawson (Flatiron Books, $26.99).

Must be addressed: Deep South by Paul Theroux (Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,$29.95) -- A disappointing, lazy book from a usually reliable writer. Theroux came to the South with an agenda, and found support for his preconceptions. It's not terrible, but it's not good either.

Finally: Because I contributed to them, two worthy books went unreviewed in our newspaper last year: Pauline Kael: Critics, Filmmakers and Scholars Remember an Icon, edited by Wayne Stengel (Rowman & Littlefield, $75), and Scar: An Anthology, edited by Erin Wood (Et Alia, $21.95).

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 01/03/2016