Since 1978, A. Scott Berg has made a living making iconic figures seem less like marble statues and more like real people. He has chronicled the lives of Katharine Hepburn, legendary producer Samuel Goldwyn and President Woodrow Wilson, and won a Pulitzer Prize for his biography of aviator Charles Lindbergh. While the subjects for his books would seem like naturals for movies (Steven Spielberg has had an option on Lindbergh), the first film adaptation of his work is based on a man most people have never heard of.

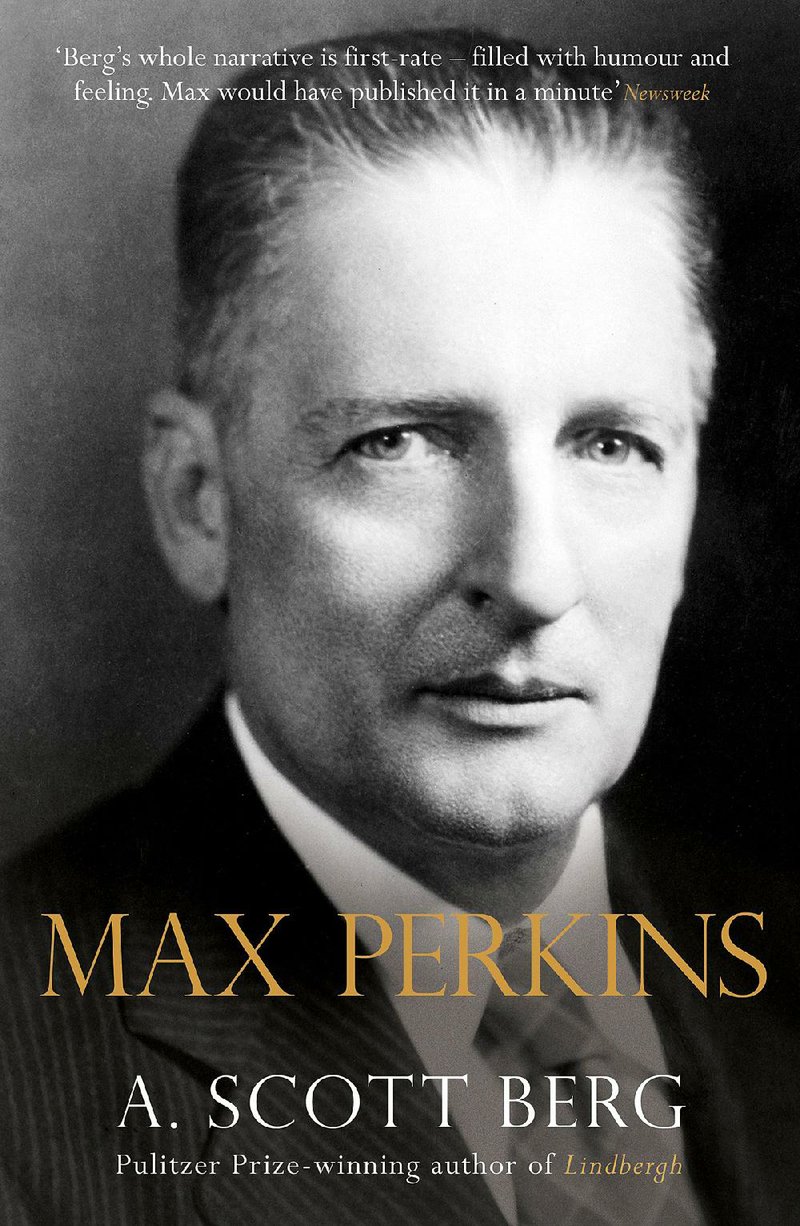

Berg's first book, Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, is the basis for Genius, a movie that will be released on home video Tuesday. The film is about the man who became the editor-in-chief at publisher Charles Scribner's Sons, now a branch of Simon & Schuster. But if Perkins' name isn't familiar, the authors he discovered and edited are. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (The Yearling) and James Jones (From Here to Eternity) all wrote masterpieces under his guidance.

Berg explains that Perkins (played in the film by Oscar-winner Colin Firth) made an indelible mark on literature without overwhelming the people whose names appeared on the spine.

"It's hard to label it, but I would say this: Perkins was drawn to singular voices," Berg says. "He didn't want writers who sounded like any other. That's what he had an ear for because he had read a lot. When he heard a voice that was different, that drew him. So even when he met James Jones, who came in with a novel Perkins didn't publish, [Perkins] recognized the freshness of Jones' voice. He said, 'Do you have any other ideas for books,' and that's when he talked about From Here to Eternity, and Perkins said, 'I'll give you a contract on that book you haven't even written yet instead of the one you have written.'"

If Perkins had a gift for finding writers who defied convention, in his own understated way, so did he. Instead of merely proofreading his authors, his suggestions and alterations had little to do with dangling participles. Aspiring English majors can take heart from the fact that some of the things that bedevil them frustrated Perkins and his authors.

"Perkins' grammar was extremely good, but his spelling and punctuation were not," Berg says. "And that brings up an interesting point, which is that editing before Max Perkins required good spelling and punctuation. It was largely a mechanical profession, preparing manuscripts for the printer. It was really with Max Perkins where the editor stepped out of the chorus and starts to become the creative partner in producing these great books. It's really Perkins who was the first one to come up with titles and plot points and making real changes in what we now call classics."

Hour of the Wolfe

Genius focuses primarily on Perkins' challenging relationship with Thomas Wolfe, played by Jude Law. Wolfe has inspired novelists like Philip Roth and Berg himself, who researched his book from the Scribner archives at Princeton while he was a student.

"I remember when I was first reading Thomas Wolfe when I was in college starting my research on Max Perkins, and I went to my adviser, Carlos Baker, who was Hemingway's biographer, and I said, 'How can anyone become a writer? Thomas Wolfe has said it all,'" Berg says. " And Professor Baker said, 'Come back to me in a few years and tell me if you feel the same.' In many ways, I still do. I think Wolfe expressed what every writer feels in his core. He expressed all those sentiments that often go unvoiced, and Wolfe was somehow able to put them on paper."

Getting Wolfe's stories into a form where Berg and Roth could enjoy them proved to be a Herculean task for Perkins. His manuscript for Of Time and the River was an unruly mess of approximately 5,000 handwritten pages. Genius shows Law scribbling reams of paper on top of a refrigerator and turning in boxes full of material. A photo from Berg's book reveals that Genius exaggerates nothing about Wolfe's prodigious but nearly indecipherable output.

"Editing Thomas Wolfe, that is the ultimate editorial experience," Berg says. "Here was a man who was completely uncensored, clearly a genius from his brain to his hands onto the page, he could not write them fast enough. Often he would not re-read what he wrote. So that is the ultimate challenge for an editor who somehow has to find a nucleus for it, find the boundaries of it, find the stories, the drama in all of that and put it in some publishable form. That's what Perkins did. So each, in a way, had met his match.

"These manuscripts came in, and, first of all, they're almost impossible to read. And in fact a lot of Of Time and the River is riddled with errors just because they're transcription errors, and Wolfe himself never bothered to re-read some of it again. A lot of the words just got mistyped and went to the printers wrong. They hired a team of typists just to type all that. These people were just trying to figure out Thomas Wolfe's handwriting."

So how does Berg know all of this? One thing that may have aided Berg in his research is that Perkins conducted almost all of his work through detailed letters. Thanks to the archive, it's clear that Perkins left little to the imagination, even to people like Hemingway and Wolfe.

"Writing letters was standard operating procedure, but above that, because Perkins' hardness of hearing, he conducted almost no business on the telephone, " Berg says. "So, really everything he did was in a letter. I've had a lot of editorial stuff with my editor, but I do it over the phone very often, but with Perkins, every thought got put down on paper.

"I'm basically reading other people's mail, and I'm snooping in the mailbox of America's greatest writers, who are telling things to one person they wouldn't tell their spouses."

A Personal Problem

The challenge of getting Wolfe's novels published took its toll on both men. Wolfe thanked Perkins in the the preface of Of Time and the River, but left Scribner to escape Perkins' formidable shadow.

He never got away. Wolfe's last two novels were published after his death in 1938 at the age of 37. Even after switching publishers and dying, Wolfe needed and got Perkins' guidance.

"He left those manuscripts behind, went on his trip [to Seattle], died, and the only person who could edit them was Max Perkins," Berg says."First of all, he was the only one who could read some of the handwriting. A lot of it hadn't been transcribed. Second, he was the only one who knew where all the pieces fit. He had the duty of editing those books and sending them on to Harper's [& Brothers Publishers]."

By the Letter

Berg seems giddy about the way screenwriter John Logan and director Michael Grandage have handled his material. When asked about the film, he uttered words that authors of the source material rarely say. "Everything in that movie is true," he says. "It's just the way it was. These people were larger than life. They were almost all operatic characters.

"It was John Logan's bravery -- artistic and financial. I just learned recently that the money he put down to buy the film rights were the first dollars he had made in Hollywood. He had written Any Given Sunday, and he basically took all of that money and put it all on Perkins."

MovieStyle on 09/02/2016