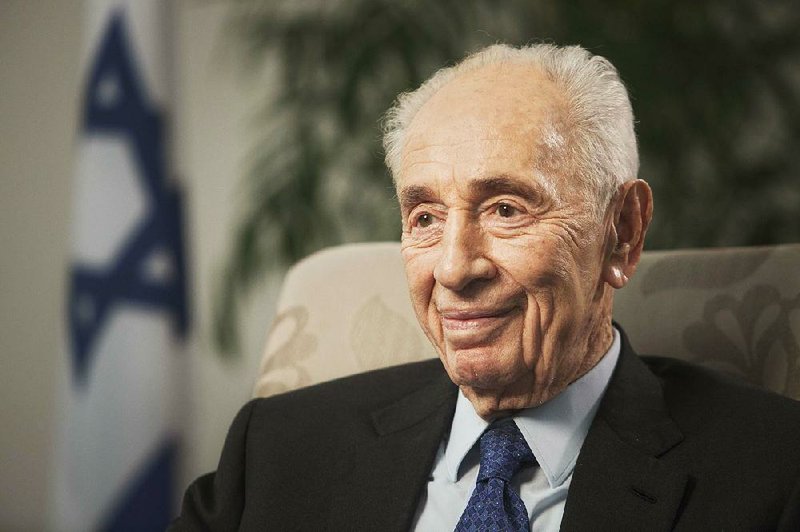

JERUSALEM -- Shimon Peres, a former Israeli president and prime minister and Nobel prize-winning visionary who pushed his country toward peace, has died, the Israeli news website YNet reported early this morning. He was 93.

Peres' condition worsened after a stroke he suffered two weeks ago. Doctors kept him largely unconscious and on a breathing tube since then in hopes that it would give his brain a chance to heal. But he deteriorated as the nation he once led watched his last battle play out publicly and leaders from around the world sent wishes for his recovery.

His son, Chemi, confirmed his death this morning to reporters gathered at the hospital where Peres had been treated for the past two weeks.

"Our father's legacy has always been to look to tomorrow," Chemi Peres said. "We were privileged to be part of his private family, but today we sense that the entire nation of Israel and the global community share this great loss. We share this pain together."

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu issued a statement mourning the passing of Peres. He said he would convene his Cabinet for a special session later today.

In a seven-decade political career, Peres filled nearly every position in Israeli public life and was credited with leading the country through some of its most defining moments, from creating its nuclear weapons program in the 1950s, to disentangling its troops from Lebanon and rescuing its economy from triple-digit inflation in the 1980s, to guiding a skeptical nation into peace talks with the Palestinians in the 1990s.

A protege of Israel's founding father David Ben-Gurion, he led the Defense Ministry in his 20s. He was first elected to the parliament in 1959 and later held every major Cabinet post -- including defense, finance and foreign affairs -- and served three brief stints as prime minister. His key role in the first Israeli-Palestinian peace accord earned him a Nobel Peace Prize and revered status as Israel's then most recognizable figure abroad.

And yet, for much of his political career he could not parlay his international prestige into success in Israeli politics, where he was branded by many as both a Utopian dreamer and political schemer. His well-tailored, necktied appearance and swept-back gray hair seemed to separate him from his more informal countrymen. He suffered a string of electoral defeats: Competing in five general elections seeking the prime minister's spot, he lost four and tied one.

For someone who was dogged for decades by a reputation for vanity and backroom dealing, Peres ended his years in public office as a beloved figure, promoting the country's high-tech prowess and cultural reach, a founding pioneer who set an example for forward thinking.

Peres said of his career: "For 60 years, I was the most controversial figure in the country, and suddenly I'm the most popular man in the land. Truth be told, I don't know when I was happier, then or now."

He finally secured the public adoration that had long eluded him when he has chosen by the parliament to a seven-year term as Israel's ceremonial president in 2007, taking the role of elder statesman in a largely ceremonial role.

Oslo Accords

In his efforts to help Israel find acceptance in a hostile region, Peres' biggest breakthrough came in 1993 when he worked out a plan with the Palestine Liberation Organization for self-government in Gaza and in part of the West Bank, both of which were occupied by Israel.

After months of secret negotiation with representatives of the PLO, conducted with the help of Norwegian diplomats and intellectuals, Peres persuaded his old political rival Yitzhak Rabin, then the prime minister, to accept the plan, which became known as the Oslo Accords.

Peres, who was serving as foreign minister, signed the accords on Sept. 13, 1993, in a ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House as Rabin and their old enemy Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the PLO, looked on and, with some prodding by President Bill Clinton, shook hands.

It was a gesture both unprecedented and historic. Up to that time, Israel had refused to negotiate directly with the PLO.

"What we are doing today is more than signing an agreement; it is a revolution," Peres said at the ceremony. "Yesterday a dream, today a commitment."

Later that day, in a television interview, Peres pronounced himself 100 percent sure that peace had arrived. With the changes in the world -- the end of the Cold War; the collapse of the Soviet Union and, with it, its military, financial and diplomatic support of the PLO; and the drying up of funds from Arab countries angered over Arafat's support of Iraq in the recent Persian Gulf War -- the time had come for the Palestinians, too, to seek peace.

"If you have children," he said, "you cannot feed them forever with flags for breakfast and cartridges for lunch. You need something more substantial. Unless you educate your children and spend less money on conflicts, unless you develop your science, technology and industry, you don't have a future."

Peres, Rabin and Arafat were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 for their efforts to settle the future of the West Bank and Gaza, which Israel had occupied since the Arab-Israeli War in 1967.

That was followed by a peace accord with neighboring Jordan. But after a fateful six-month period in 1995-96 that included Rabin's assassination, a spate of Palestinian suicide bombings and Peres' own election loss to the more conservative Netanyahu, the prospects for peace began to evaporate.

Relegated to the political wilderness, he created his nongovernmental Peres Center for Peace that raised funds for cooperation and development projects involving Israel, the Palestinians and Arab nations. He returned to it at age 91 when he completed his term as president.

Defense chief at 29

Shimon Perski was born on Aug. 2, 1923, in Vishneva, then part of Poland. He moved to pre-state Palestine in 1934 with his immediate family. His grandfather and other relatives stayed behind and perished in the Holocaust. Rising quickly through Labor Party ranks, he became a top aide to Ben-Gurion, Israel's first prime minister and a man Peres once called "the greatest Jew of our time."

Peres was married to the former Sonya Gelman, who shunned the spotlight to the point of refusing to move into the president's house when he took his last public post. She died in January 2011. They had three children. They and Peres' eight grandchildren and three great-grandchildren survive him.

When Israel became independent in 1948, Peres was named head of the naval service at age 27.

At 29, he was the youngest person to serve as director of Israel's Defense Ministry and is credited with arming Israel's military almost from scratch, even though he never wore an army uniform or fought in a war.

Peres ran for the country's parliament, the Knesset, in 1959, in his first bid for national elective office. With the support of Ben-Gurion, he was given a position high enough on his party's electoral list to be assured of victory.

He served through the political turmoil that preceded the 1967 Middle East War and subsequent crises, including the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the 1976 hijacking of an Air France flight that held about 100 Israeli passengers.

Peres finally became prime minister in 1984 when he led his Labor Party into the coalition with Likud.

Shunted aside during the 1999 election campaign, won by party colleague Ehud Barak, Peres rejected advice to retire, assuming the newly created and loosely defined Cabinet post of Minister for Regional Cooperation.

In 2000, Peres lost an election in the parliament for the largely ceremonial post of president to the Likud Party's Moshe Katsav, who was later convicted and imprisoned for rape.

Even so, Peres refused to quit. In 2001, at age 77, he took the post of foreign minister in the government of national unity set up by Ariel Sharon, serving for 20 months before Labor withdrew from the coalition.

Then he followed Sharon into a new party, Kadima, serving as vice premier under Sharon and his successor, Ehud Olmert, before assuming the presidency.

Among his many international distinctions, the French Legion of Honor was awarded to Peres in 1957. In 2012, President Barack Obama presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In a statement from the White House after Peres' death, Obama lauded the Israeli as a statesman whose commitment to Israel's security and the pursuit of peace "was rooted in his own unshakable moral foundation and unflagging optimism."

Obama said that Peres looked to the future, "guided by a vision of the human dignity and progress that he knew people of goodwill could advance together."

"A light has gone out, but the hope he gave us will burn forever," the statement said.

Information for this article was contributed by Aron Heller and staff members of The Associated Press and by Marilyn Berger, Isabel Kershner and Ethan Bronner of The New York Times.

A Section on 09/28/2016