There is a terrible song my father loved.

It was written and performed by Harry Chapin, who may be best known for a good/bad song called "Taxi," about a guy who couldn't achieve his dreams and ends up driving a cab in San Francisco. I used to dislike that song because it seemed like what we these days call "a humblebrag." After all, the guy singing it hadn't failed to achieve what he'd set out to achieve; he hadn't compromised and given up on his talent and ended up something quotidian that almost anyone could do for a living. It struck me as a special kind of sneering, like what Dan Fogelberg does in "Same Old Lang Syne," about a chance encounter with an old lover. The lines in the Fogelberg song that grate on me are:

She said she's married her an architect

Who kept her warm and safe and dry

She would have liked to say she loved the man

But she didn't like to lie

The implication is she settled for this dude when she could have had Danny Coolbeard. That's the sort of thing that's always put me off certain writers; I don't mind the artistic hubris so much as the contempt for folks who have to make a living. An architect or a cab driver can be just as soulful as a crafter of pop songs.

But I changed my mind about "Taxi." Most of us are like the guy driving the taxi who never learned to fly. While there's a certain melodrama to "Taxi," it's really not a bad song -- it recognizes that real life isn't like the movies and that all of us sooner or later have to make pragmatic choices. At some point you'll take the money -- you'll stuff the bill in your shirt.

I'm OK with Chapin and with Fogelberg too -- both died too young. Both did what they could with what they had. While I identify more with the grunt in "Taxi" than with the nostalgia-bit pop star in "Same Old Lang Syne," I admit that both of these songs feel like they were drawn from authentic experience.

It's my job to think about these things. I calls 'em as I sees 'em -- even as I understand that I'm as likely to misperceive the artist's intention as anyone else without access to the artist's subconscious. Most of the time, even with relatively literate songwriters, the words are just there to pin down the notes.

The terrible song my father liked so much was not "Taxi" but "Mr. Tanner."

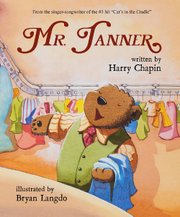

Like most of Chapin's songs, it told a story. (By sheer coincidence, I've discovered that an illustrated children's book based on the song is due to be released next month.) This story was about a Midwestern dry cleaner who sang in amateur productions, who was encouraged by his friends to rent a hall in New York and try to make a career as a professional singer. But when he got to the stage, he wasn't so good as his friends believed he was.

He was succinctly destroyed by a music critic who "only took four lines."

Chapin helpfully gives us the review in a spoken word interlude -- "Mr. Martin Tanner, a baritone, of Dayton, Ohio, made his town hall debut last night. He came well prepared, but unfortunately his presentation was not up to contemporary professional standards. His voice lacks the range of tonal color necessary to make it consistently interesting. Full-time consideration of another endeavor might be in order." -- before hitting the payoff couplet:

He came home to Dayton and was questioned by his friends

But he smiled and said nothing and he never sang again.

My father thought it horrible what the critics did to Mr. Tanner. (And who wouldn't? The critic stepped on the throat of the man's dream, shamed him and sent him back home to Ohio, abashed and -- worst of all -- silenced forever. What a bad man the critic must have been.)

Chapin was inspired to write the song by a 1972 New York Times review of a recital by a baritone named Martin Tubridy at New York's Town Hall. Allen Hughes' review really was only four lines long, and it ended with the line:

"He was well prepared and sang conscientiously, but the results were not up to generally accepted levels of professional accomplishment." Tubridy didn't like the reviews but they didn't stop him from singing and performing -- you can even find him on YouTube singing "Mr. Tanner" with Harry's brother Stephen. You can find lots of clips of him on his website martintubridy.com

Mr. Tanner's heartbreak was schmaltz -- boody hoody hoo, you didn't get to be on the big show. But Tubridy's persistence is working-class heroic. You just keep doing it.

My father, who died decades ago, didn't think much about such things. He was an athlete and a military man, an autodidact who earned a college degree after he was fully adult, with a family. Thanks to the Air Force, he traveled the world and grew used to living and working with people much unlike himself.

I believe he was very bright, but his personal library was small and eclectic, and he tended to reread the books he loved -- Tennyson's poetry, Bulfinch's Mythology and Mickey Spillane's paperbacks. He admired John Cheever; he thought Norman Mailer was a boorish clown. He liked cowboy movies, especially those with Dean Martin, but he didn't care for John Wayne, who reminded him of a swaggering football coach. He liked Jim Reeves and Marty Robbins; the Beatles threw him a little. Their early records -- yeah, yeah, yeah -- sounded childish to him, and he never gave their later stuff a chance.

He preferred Charles Bronson to Clint Eastwood, Redd Foxx's Fred Sanford to Carroll O'Connor's Archie Bunker. He watched ballgames and sometimes Johnny Carson. He wasn't trying to project a brand image or advertise his erudition. There were three channels and, like a good Depression child, he was trained to consume what was put before him. He was more Chet Huntley and David Brinkley than Walter Cronkite, part of Nixon's silent noncomplaining majority. He grumbled about politics but was not completely parsable. I was very surprised to learn -- in the last weeks of his life -- that he had taken steps to keep me from going to Vietnam (the war and the draft ended before I turned 18).

...

In many ways my father is mysterious to me, as we all are to each other. He could not tell me who his father was, or what it was that I should do with my life. And though I am probably more like him than not, there were parts of each of us that the other could not know. He definitely identified more with the working stiff in "Taxi" than the artiste in "Some Old Lang Syne." While he didn't sing or write or paint, he was sympathetic to the Mr. Tanners he knew in real life.

I don't think he considered critics worth much thought. But he could quote from the speech Teddy Roosevelt delivered at the Sorbonne in 1910:

It is not the critic who counts ... the credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly ... and who at the worst ... at least fails while daring greatly.

I know those words well. (I keep a copy of the entire speech in my desk drawer.) Three or four times a year someone balls them up and throws them at me in an email or a letter, with the implication that it is not my words that count. They are trying to hurt my feelings, usually because I have written or said something about a movie or a book or a piece of music with which they do not agree. Maybe they think I was trying to make them feel stupid for liking or not liking whatever it was that I liked or didn't like. I don't know. I'm not responsible for them.

I almost agree with them.

I think a lot about Mr. Tanner these days when I go through various piles of books and records and movies on my desk. There's no way to review them all, there's no way to allow each of them the chance they deserve to work whatever magic they may have. I have to judge a lot of books by their covers; if I recognize the author's name I'm more likely to read a little bit. If something looks professionally put together, it's more likely to get more attention.

The other day I got a novel from a well-spoken 15-year-old (he called me to ask if it was OK to send the book; I didn't know how old he was until he mentioned it in a follow-up email). I was intrigued, but then I noticed a typo on the cover. And the first paragraphs I read at random were ... well, if I were to review it, it might sound a lot like what Allen Hughes wrote about Martin Tubridy. Enthusiasm and yearning aren't enough.

That doesn't mean the kid couldn't be good some day. Only that right now, with this piece, "the results were not up to generally accepted levels of professional accomplishment." That's the truth, and it's important that the artist hear it.

And the critic can be wrong. Critics are wrong all the time.

About the best you can do is not let yourself become the self-regarding guy in "Same Old Lang Syne." You've got to be the grinder in "Taxi." You have to know your limitations if you're going to convert them into virtues. Everyone who writes for a general audience is likely to sometimes feel that readers and editors are playing defense against their work. Writing about pop culture isn't hard -- often you can get by with a smirk. But the real job of criticism is to at least try to break through the shell of reductive cliche and facile assumptions and tell the truth about what is, after all, a commercial venture.

It is not a critic's job to shame you for liking what you like or for not liking what you ought to like. It's not the critic's job to tell you what to think, only to remind you that thinking is an option.

It is my job to hold art up to the light, to look for the flaws, the cracks that let in the light, to paraphrase Leonard Cohen -- but not to precisely weigh, measure and declare its worth. All I want to do is to say something interesting. On a good day, perhaps I can point something out you haven't noticed.

I write about movies and books and music because it's fun for me to think about things, because considering art is one of the great pleasures available to sentient beings. It is good to think about what things mean and to play with meaning and perception. To switch off the light and see if the damn thing glows. To switch the light back on and watch the roaches scuttle.

Look, T.R., I feel like I am in the arena. Not as a referee either, but as a performer.

Mr. Tanner, c'est moi too.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 04/16/2017