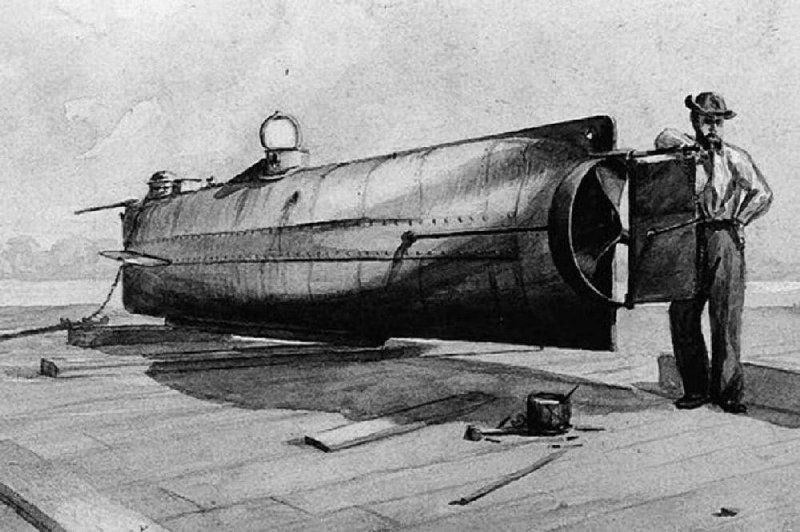

Cheers rose when the H.L. Hunley broke the ocean's surface for the first time in more than a century. Since it vanished during a 1864 naval battle, the Confederate submarine had sat on the seafloor off the coast near Charleston, S.C., its heavy iron hull gathering barnacles and rust.

In 2000, when the vessel was recovered, scientists and historians expected to be able to solve the mystery of why it sank.

But when they ventured into the boat, they found not a single clue. Its 40-foot-long iron hull was barnacle-encrusted but not broken. The skeletons of eight members of the crew were found still in their seats at their respective battle stations. Their bones bore no evidence of physical harm. The bilge pumps hadn't been activated. The air hatches were closed. There was no sign that anyone had tried to escape.

"There was nothing on the boat that could explain the deaths," said Rachel Lance, a biomedical engineer at the University of North Carolina.

In a paper just published in the journal PLOS One, Lance and her colleagues report that it was something in the water that led to the submarine's demise, something the crew had put there themselves. They were killed by their own weapon.

Lance figured this out without experience in archaeology or access to the sub itself. Indeed, the majority of her research was conducted in a pond.

The Hunley was intended to be the Confederacy's secret weapon. Though boats capable of operating underwater had been built before the Civil War, none had been successfully deployed against an enemy ship.

On Feb. 17, 1864, the sleek iron vessel slid unnoticed into Charleston Harbor, which was blockaded by the U.S. ship Housatonic. The Hunley's crew pointed a torpedo packed with explosive black powder at the Union boat's hull, aimed it and fired.

The Housatonic sank. And then, seemingly for no reason, the Hunley did, too.

A few years ago, the mystery fell into Lance's lap. She specializes in trauma related to underwater blasts, and at that time she was a researcher for the Navy working on her Ph.D. at Duke University. One of her professors wanted to know whether she could apply her work to the Hunley case.

"Hollywood does a really poor job of showing what happens in an explosion," Lance said. "People aren't thrown that often."

Instead, when a torpedo blows something up underwater, it creates pressure waves that reverberate in the water and through the body of anyone who happens to be in it. The instantaneous increase in pressure can squeeze oxygen out of the lungs and pop blood vessels in the brain. The effects are often deadly.

The damage occurs exclusively in a victim's soft tissue, like the gut, lungs and brain. From the outside, it can be impossible to tell that the person has been harmed.

Lance has studied thousands of blast trauma deaths of World War II sailors who were killed by explosions that caught them in the water during the Battle of Midway. She has also advised the Navy on the safe distance for divers trying to disarm unexploded ordnance at the bottom of the sea.

As soon as she read the description of the remains of Hunley's crew, "we realized that what the archaeologists had uncovered were patterns of trauma that looked exactly like blast injures," she said.

But where did the pressure waves to cause that trauma come from? The most likely answer was the Hunley itself, or rather, the torpedo that the Hunley had fired at the Housatonic moments before.

Lance and her colleagues constructed a 6-foot scale model of the Hunley out of historically accurate sheets of iron, and dubbed the vessel CSS Tiny. They placed it in a pond on Duke University's campus, then pumped a puff of compressed gas into the water near the little ship to replicate the effects of a bomb exploding.

Sensors located on every surface of the Tiny indicated that the waves hit the underside of the hull and were deflected, setting off a secondary pressure wave that bounced around the vessel's interior.

Next they replicated the experiment using real blasts of black powder, the world's most ancient explosive, which was the active ingredient in the Hunley's torpedo.

This phase was conducted in an off-campus pond, where it wouldn't harm any hapless undergrads. But it produced the same results: The pressure along the Hunley's keel was about 1,100 pounds per square inch, equivalent to being beneath 2,400 feet of water. Inside the ship, the pressure jumped to at least 28 psi after the explosion, similar to diving to 64 feet below the surface.

That may not sound like much, but the increase happened almost instantaneously. "It is the rapid rate of increase that causes the trauma," Lance said. She and her colleagues calculated that there was an 85 percent chance that the crew of the Hunley died of pulmonary problems caused by the dramatic wave of pressure. They could have died before they knew what was happening.

Robert Salzar, a blast injury biomechanics specialist at the University of Virginia, told Nature that blast trauma is usually not instantly deadly. Instead, he suggested, the pressure waves may have killed the crew indirectly by knocking them out and causing the Hunley, with no one conscious to steer it, to sink.

The absence of an autopsy makes it impossible to know for sure, Lance said, but this is the first theory that accounts for all the odd clues archaeologists have uncovered. In Lance's mind, at least, "I think the mystery is solved."

SundayMonday on 08/27/2017