V.L. Cox looks around her spacious North Little Rock art studio and feels a sense of loss.

"I can hear an echo in the room when I talk, it's really weird," she says. "I haven't seen it this empty since I moved here three years ago."

Cox's studio feels empty because it nearly is. More than 50 multimedia sculptural works from her "End Hate" series are gone, taken away by the Longwood Center for the Visual Arts in Farmville, Va. They will be the heart of Cox's first solo museum show outside Arkansas, "Break Glass: The Art of V.L. Cox -- A Conversation to End Hate." It opens with a reception at 5 p.m. Nov. 3 at the museum, which is part of Longwood University. The exhibition continues through Feb. 18.

"I have some separation anxiety," Cox says with a slightly nervous laugh. "When you are completely surrounded by your work, you always feel you are part of something bigger than yourself. I have a powerful connection to those creations."

So does Rachel Ivers, executive director of the Longwood Center, who first saw Cox's work in an exhibition catalog.

"We have a collector who recently relocated to our area; she sent me a catalog of V.L. Cox's art and said she thought I might like her work. She was right. I connected with it immediately. When I saw the work in person, it made me very quiet. Her work causes you to reflect.

"She delivers her message; it's strong, pointed, but in a way that people can understand and reflect on it. Cox's call for greater empathy and people talking to one another resonates with a lot of people. She's very clear."

Longwood University and the museum are in Prince Edward County, the same county as the Robert Russa Moton High School. In 1951, a student-led walkout and strike protested overcrowding and unequal facilities at the black school. A resulting lawsuit was incorporated into the historic Brown v. Board of Education lawsuit that resulted in a 1954 Supreme Court decision that ruled against the principle of "separate but equal" facilities and mandated school integration.

The Moton school is now a civil rights museum.

"This area of Virginia has a long history with contentious racial issues, but it's always been very civil. We are in a small town, but we have a lot of people who work and advocate for a better world."

Ivers says she was shocked when she heard about what happened in Charlottesville, Va., on Aug. 12, when a white supremacist rally protesting the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee from a public park turned deadly.

Charlottesville is about 60 miles north of Farmville.

"Many of us were surprised by the events there," she says. "It made us a bit apprehensive, but I think this exhibition is going to be very positive."

In the museum's news release about the exhibition, Ivers says "If we are ever to come close to ending hate and its attributes of bigotry, racism and injustice, we must confront its ugly legacy as well as be able to recognize all of the comfortable places in which it hides."

Cox hopes "Breaking Glass" will be a "conversation starter about these issues."

"I believe it will be, but it has to take a path of its own. This is about the work, the message, not me. The stories about this work are real. It's about history, where we've been and where we can't allow ourselves to go again. I'm a human rights artist. Discrimination never stops with one group if it's allowed to happen."

...

Parts of the "End Hate" collection have been shown in various places around the state, including a 2016 show, "A Murder of Crows," at Little Rock's New Deal Studios. "The End Hate Door Collection" has been especially visible. Cox created the door installation in 2015 in response to the Arkansas Legislature's consideration of House Bill 1228, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, legislation seen by some as a reaction against the legalization of same-sex marriage.

Cox painted six doors different colors, adding labels that evoke Jim Crow-era society and beyond: "Whites Only," "Colored Only," "LGBT Only," "Immigrants Only," "Homeless Only" and "Human Beings." The doors were placed twice at the state Capitol, at the base of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, and several sites in Arkansas, including the Arkansas Arts Center during a broadcast of Tales from the South.

The doors will be "the first thing you see when you walk into the exhibition," Cox says. "They were the catalyst for the series. They have traveled over 7,000 miles so far, and the end of their journey is nowhere in sight."

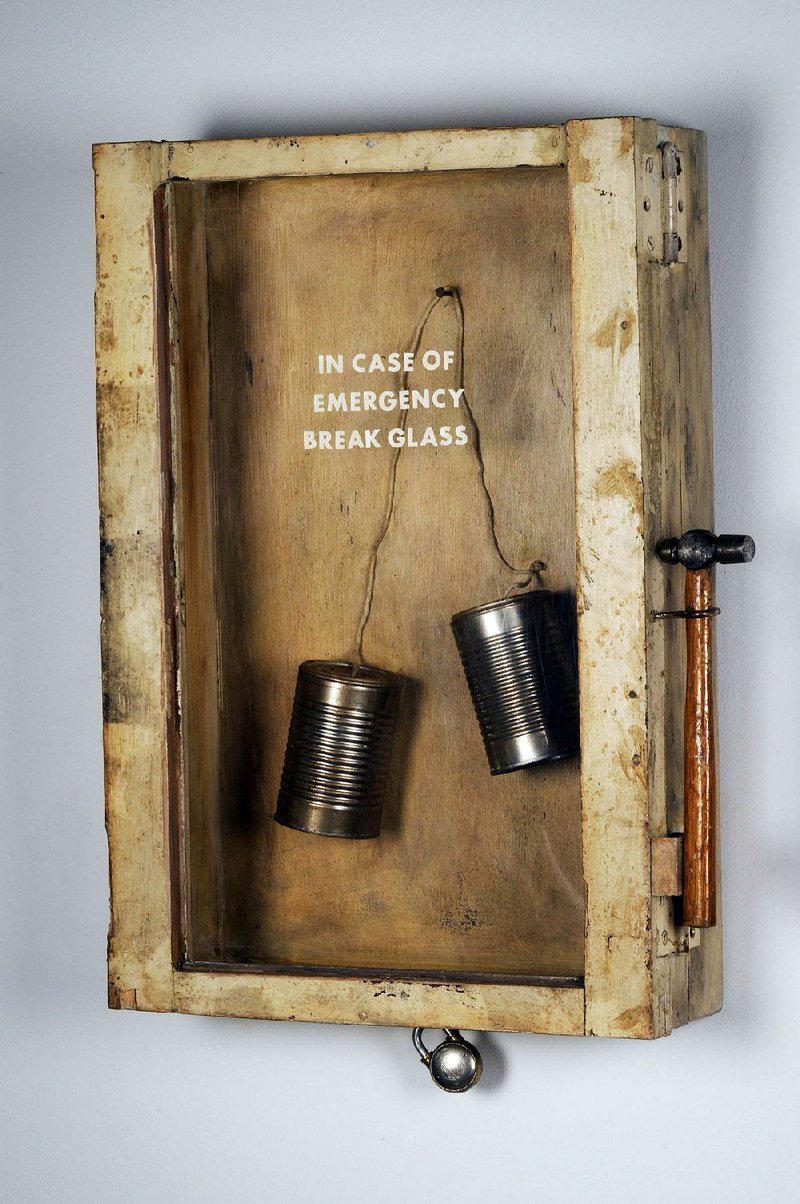

The title for the Longwood exhibition was inspired by Cox's work It's Time We Start Over and Talk About Hate, which is the official image for the exhibition. The work has a toy for communication -- two cans, connected by string -- hanging inside a 1940s display case. The glass front, inscribed with "In Case of Emergency Break Glass," is a re-sized 1950s wooden window. A 1920 church communion cabinet padlock secures the window. A hammer hangs at the side.

In the catalog for "A Murder of Crows," Cox writes about the piece: "When hate escalates to violence, it IS an emergency. It's time to go back to the basics, start from the beginning, and learn to talk to one another. This is why I used an image of a simple child's toy for the subject matter."

Part of the problem, Cox believes, is how people communicate -- or don't.

"We are a media-driven society, yet our ability to make the time to talk to each other without doing it through a keyboard is crucial," she says. "We are losing our touch with humanity. Personal conversations, with respect to one another, need to be had before we can move forward together. There used to be a time when people could agree to disagree with civility, yet still have things in common. We need to find that place again."

Outgoing and warm, Cox has an intensity that shows in her art. But even the most driven of artists needs a break.

"I love to wake up in the morning, grab a cup of coffee, sit down on the back deck and write. I love to write short stories, and I am currently 80 pages into my first novel. I love the outdoors and enjoy hiking, fishing and taking photographs."

In her art, Cox also draws on her Southern background. Born in Shreveport and reared in Arkansas, Cox tapped that upbringing in her "Images of the American South" series of narrative portraits of people painted behind screen doors.

What does Cox hope people take away from her art?

"The goal is to engage viewers responsibly in a dialogue no matter how uncomfortable. In a world where we can't remember what we had for lunch yesterday, uncomfortable social and historical events are often quickly dismissed and filed away in the recesses of our busy minds. [The art] confronts our historical 'amnesia' and issues that are uncomfortable to talk about, but ones that we must address before any change can take place."

Cox also finds enjoyment is seeking unique historical objects to create her artworks.

"I believe these pieces always find me and I feel the connection immediately," she says. "It never fails, whenever I have a project in mind that I feel very passionate about, the material always presents itself and tends to come together seamlessly. There are times I feel so connected to these pieces and projects, it's like I'm one with it as we work together to convey a visual message.

"In surrendering myself to this creativity, I have noticed that I now see the world and everything in it through entirely different eyes. An old wooden piece that I wouldn't have paid any attention to a few years ago is now the Holy Grail to me when I see where it truly belongs in my work. They all have a story, they connect us, and their familiar appearance, feel and even smell create a primal, tactile sensory experience that awakens our memories.

"They remind us of the lessons we have forgotten, and once again need to learn by encouraging diverse dialogue and conversation about social issues addressing our society today."

Therein lies Cox's artistic motivation:

"I want to make a difference in the world; I believe that's what art can do."

Info: lcva.longwood.edu

Style on 10/22/2017