CHICAGO -- Medical student Alejandra Duran Arreola dreams of becoming an OB-GYN in her home state of Georgia, where there's a shortage of doctors and one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the U.S.

But the 26-year-old Mexican immigrant's goal is now trapped in the debate over a program protecting hundreds of thousands of illegal aliens like her from deportation. Whether she becomes a doctor depends on Congress finding an alternative to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program that President Donald Trump phased out last month.

Arreola, who was brought to the U.S. at age 14, is among about 100 medical students nationwide who are enrolled in the program, and many have become a powerful voice in the immigration debate. Their stories have resonated with leaders in Washington. Having excelled in school and gained admission into competitive medical schools, they're on the verge of starting residencies to treat patients, a move experts say could help address the nation's worsening doctor shortage.

"It's mostly a tragedy of wasted talent and resources," said Mark Kuczewski, who leads the medical education department at Loyola University's medical school, where Arreola is in her second year. "Our country will have said, 'You cannot go treat patients.'"

The Chicago-area medical school was the first to openly accept deferred-status students and has the largest concentration nationwide at 32. California and New York also have significant populations, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program gives protection to about 800,000 people brought to the U.S. as children and who otherwise would lack legal permission to be in the country. They must meet strict criteria to receive two-year permits that shield them from deportation and allow them to work.

President Barack Obama created the deferred-status program in 2012. Critics call it an illegal amnesty program that is taking jobs from U.S. citizens. In rescinding it last month, Trump gave lawmakers until March to come up with a replacement.

Medical students such as Arreola are trying to shape the debate, and they have the backing of influential medical groups, including the American Medical Association.

Arreola took a break from her studies last month to travel to Washington with fellow Loyola medical student and program participant Cesar Montolongo Hernandez to talk to stakeholders. In their meetings with lawmakers, they framed the program as a medical necessity but also want a solution for others with deferred status.

A 2017 report by the Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a shortfall of between about 35,000 and 83,000 doctors in 2025. That shortage is expected to increase with population growth and aging.

Hernandez, a 28-year-old from Mexico simultaneously pursuing a doctorate, wants to focus his research on early detection of diseases. His work permit expires next September, and he's worried he won't qualify for scientific research funding without the program.

Medical school administrators say the immigrant students stand out even among their accomplished peers: They're often bilingual and bicultural, have overcome adversity and are more likely to work with underserved populations or rural areas.

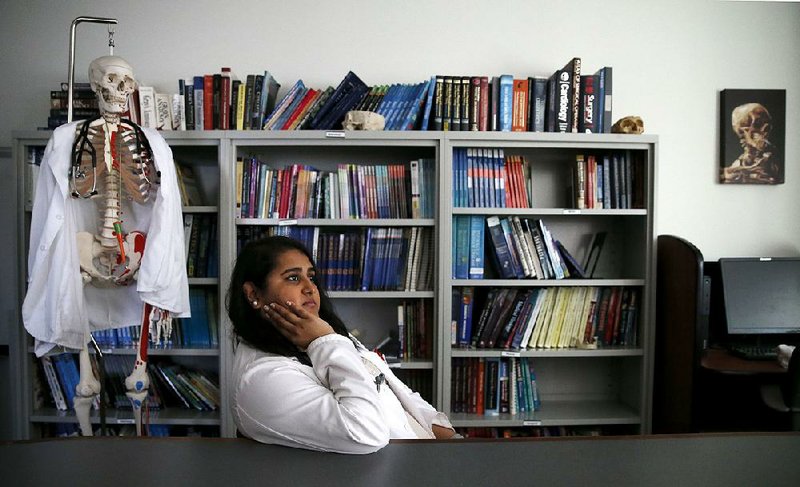

Zarna Patel, 24, is a third-year student at Loyola who was brought to the U.S. from India as a 3-year-old. Her deferred-status permit expires in January, and she's trying to renew it so she can continue medical school rotations that require clinical work. If she's able to work in U.S., Patel will go to disadvantaged areas of Illinois for four years, part of her agreement to get school loans.

"Growing up, I didn't have insurance," she said. "I knew what that felt like, being locked out of the whole system."

A Section on 10/22/2017