"There is the view that poetry should improve your life. I think people confuse it with the Salvation Army."

-- John Ashbery

Every generation suffers its losses, slips back a little even as its technology progresses. We bury our heroes and our children forget them.

There was a mild disturbance in the matrix when John Ashbery died recently; he was an old man whose name might sound familiar. He might have been a little famous, the sort of name that rates a feature obituary sent out on the wires to rattle around the world. But just a little rattle, just a little hum.

(The ceasing of a signal. The stilling of a drum.)

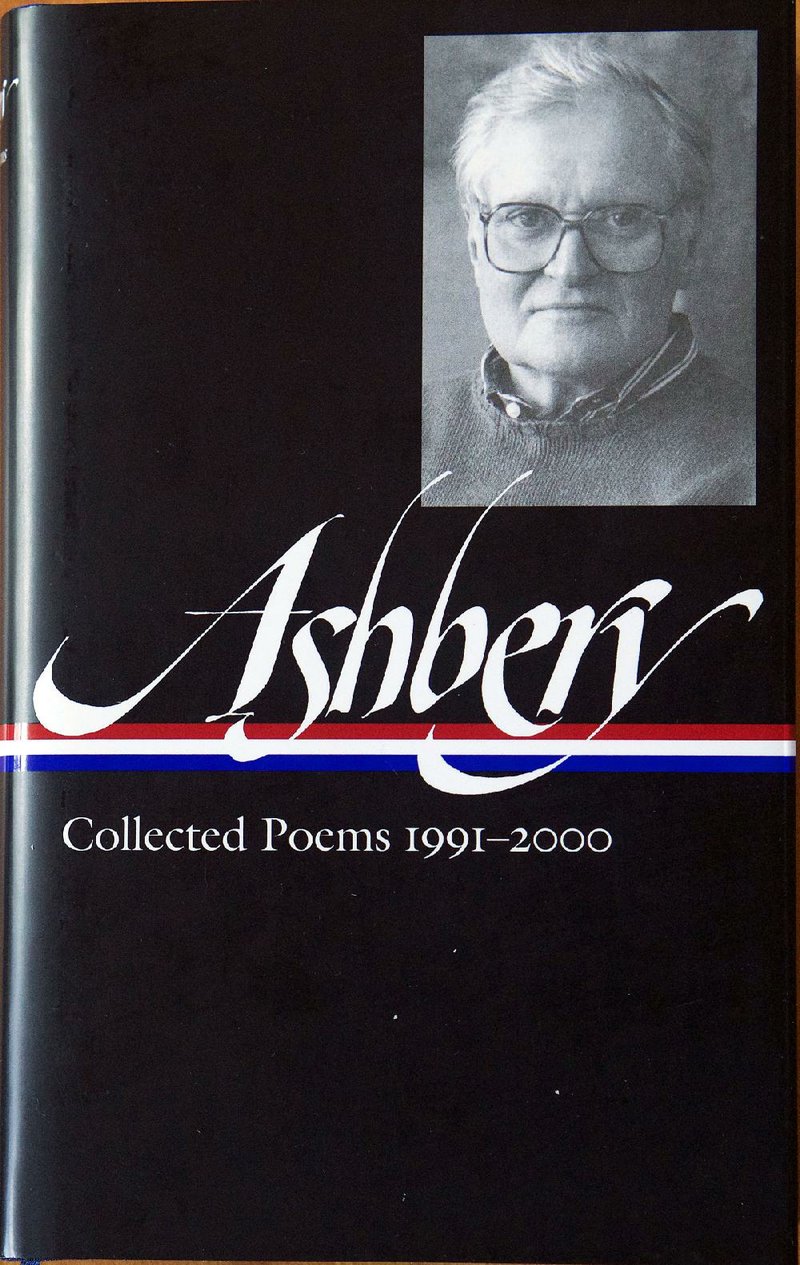

As it happened I'd been reading him recently -- it feels more correct to say I've been reading in him, for Ashbery is an oceanic subject -- having been sent an advance copy of Collected Poems 1991-2000 (Mark Ford, editor, Library of America, $45), the companion volume to Collected Poems 1956--1987, published in 2008. After Ashbery's death on Sept. 3, the Library of America moved up the publication date. It's out now and I wish more people would read it than will.

In his memorial essay in The New Yorker, Ben Lerner quoted Ashbery's 1957 review of Gertrude Stein's posthumous poetry collection Stanzas in Meditation: "The poem is a hymn to possibility; a celebration of the fact that the world exists, that things can happen."

"It remains among my favorite descriptions of John's own work," Lerner writes.

For me, the only reason to read poetry is to get drunk on it, to let the rhythms and the parlance batter you into something like senselessness or nirvana, some exalted or beaten-down state where all that matters is how the chords resolve. And I understand the world at large is too practical and rough a place for poets, which is precisely why some of us need them, especially a nominally post-modern poet like Ashbery, who sometimes seem so removed from the way most of us have to live our lives. There is no plot to him, no argument that sustains -- at times it seemed Ashbery, like Chuck Berry, had no particular place to go.

He's there in the work-shed in "Taxi in the Glen," telling some young girl relation about his collection of antique lard cans:

You know, some day there'll be an interest

in these, though it will peak, like a tide,

in infinite relief, and be back next day.

But somebody will surely remember them --

the succinct red of that metal.

That's not a major poem of his, at least not by the lights of the world. (Google it and see.) But it is one that I remembered, one that has a hint of avuncular malice showing through its autumnal glow. Here is Wallace Stevens, with a razor in his sock.

It was published in Can You Hear, Bird (1995), which is one of the seven books along with 26 previously uncollected poems that make up the volume. It opens with Ashbery's 224-page Flow Chart (1991), a experimental stream-of-consciousness work that alternately evokes James Joyce's Ulysses and David Lynch's Twin Peaks (the original series was au courant with the poem's writing), with the banal ever breaking in on the sublime. When it was published, Scott Mahler, writing in the Los Angeles Times, suggested taking it in as one might a surrealist painting -- all at once at first, for the form and general suggestion, then close-up, to "[sort] out the meaningful passages from the balance of apparently random marks and remarks on the page."

That's a good suggestion for reading Ashbery as a whole; he often allowed the outer world into the one he was creating, his voices shift like those of Robin Williams or Jonathan Winters, his eyes wander and search. He started out meaning to be a painter, studying to that end at Harvard and Columbia before moving to Paris for a decade, where he somewhat reluctantly accepted a job as an art critic for the International Herald Tribune.

But he found his metier -- and ludicrous success -- early. The Yale Younger Poets Prize before he was 30; in 1976 he won the Pulitzer, National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award for the collection Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. He was fashionable before he was obscure, before he was our own modest genius, a strangely affable yet untouchable figure peering out at us from an obscuring tangle of black glyphs on bone white pages. He's in there somewhere, with his darts and blowgun.

"Somewhere someone is traveling furiously toward you," Ashbery once wrote of the Angel of Death, in a poem that's not collected in this volume (you have to look up "At North Farm" in Collected Poems 1956--1987), "at incredible speed."

We all have our rendezvous. Even our giants.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 09/17/2017