Every year, the federal government hosts a Veterans Day wreath-laying ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, accompanied by a display of military colors and remarks from visiting dignitaries. The ceremony honors U.S. veterans, especially those who died fighting for their country.

This year, on Nov. 11, the federal government will throw a parade to celebrate the nation's military past, including period costumes and reenactments from the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Civil War and both world wars. To accompany the soldiers and veterans, the air will be filled with many generations of military planes. The parade is intended to proclaim U.S. military dominance, rather than the typical somber reflection at the cemetery. A White House report admits that the cost for the cele-brations could exceed $30 million.

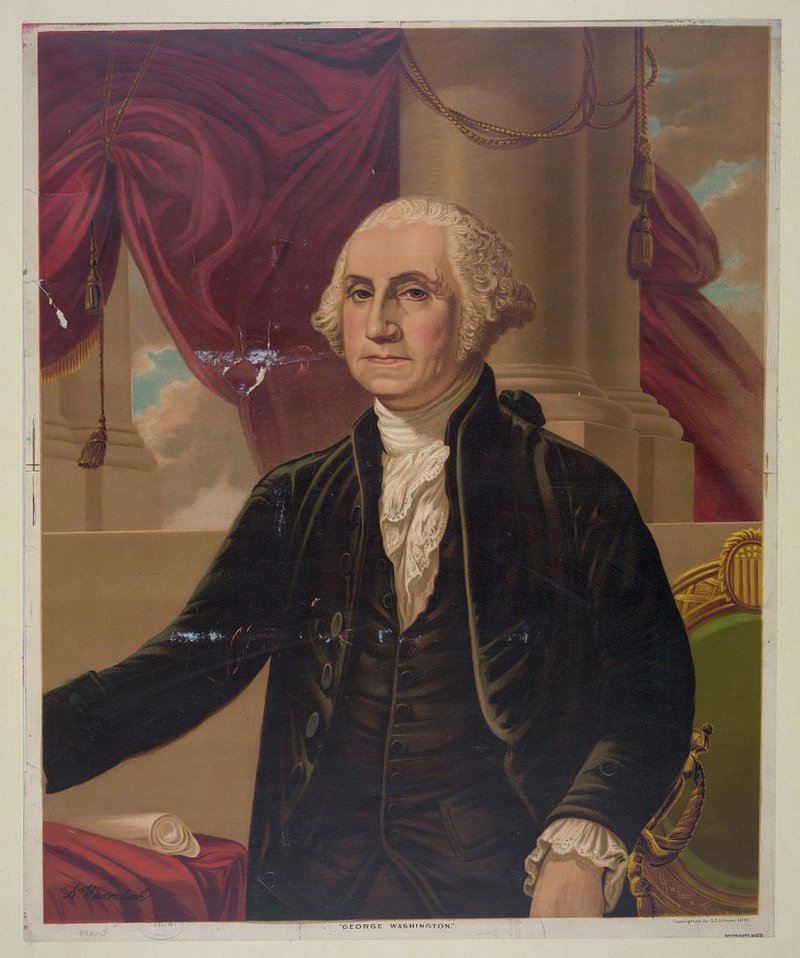

The significantly expanded parade comes at the request of President Donald Trump, in an effort to one-up the Bastille Day celebration he witnessed last July in France. By celebrating current military strength, rather than honoring veterans' service, the parade breaks with a long tradition of civilian leadership dating back to President George Washington.

Washington, the first in the pantheon of American military heroes to become president, refused pomp and circumstance as the trappings of monarchy, not a virtuous republic. If the parade occurs, it will demonstrate Trump's contempt for civilian authority and flout the established governing norms of the republic.

On Oct. 24, 1789, Washington entered Boston on the back of a large white stallion. This visit was the first time he had returned to the city since the Continental Army had liberated it from the British fleet in March 1776. Washington could have ridden into Boston a conquering hero with full fanfare--parades, feasts, military demonstrations, fireworks, cannons and countless toasts.

Instead, the day before his arrival, Washington pleaded with Gov. John Hancock to limit the celebrations. He then informed Maj. Gen. John Brooks, commander of the Middlesex Militia, that he would not review the militia or observe any special military maneuvers. As a private man, he could only pass down the line of troops assembled to greet him. There would be neither military parades nor any military operations for the newly inaugurated civilian leader.

Washington entered the presidency with more military experience than any of the 44 men who have succeeded him. He fought in two wars and served as the commander in chief of the Continental Army for eight years during the Revolution. When soldiers began toasting "Washington or no army," delegates to the Continental Congress acknowledged that Washington's leadership had become synonymous with the army and the cause for independence.

The officer corps and the soldiers deeply revered Washington, and he instilled a great loyalty in his men. When Caleb Gibbs, commander of Washington's personal guard unit, retired from Washington's service, he was so overcome with emotion that he wept as they said their goodbyes. In July 1976, Congress posthumously appointed Washington general of the armies of the United States so that no future general would ever outrank the first commander-in-chief.

Why, then, did Washington, a man intensely proud of his military service and revered for it, reject the trappings of military honor? The answer lies in his steadfast devotion to republican principles. Washington believed that for a republic to survive, civilian authority must reign supreme over the military. As commander in chief of the Continental Army, Washington repeatedly deferred to Congress' authority and judgment. He welcomed their suggestions, criticisms and participation in camp, even when he disagreed privately with their ideas.

Washington understood that he was not just fighting to win a war, but to secure independence for the new nation. Therefore, how he won the war was as important as the victory itself. If Washington seized expansive personal power at the expense of Congress, the United States would be a military dictatorship. The future of the republic required Congress to wage the war as an embodiment of the people's sovereignty and to demonstrate its control of military forces.

On Dec. 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission and handed his resignation to the Confederation Congress. When Washington was inaugurated as the first president in April 1789, he considered himself not a general but a private man, a requirement to fill the highest office in the new federal government. Washington crafted his appearance and his behavior to emphasize his civilian status. Rather than arriving in New York City to take the oath of office in one of his many elaborate military uniforms, he selected plain clothes. For the occasion, Washington had ordered a new suit made of fine brown cloth spun in the United States. (Though he still had expensive taste; he accentuated his black shoes with diamond buckles to add a bit of finery.)

Washington continued to emphasize his civilian authority throughout his presidency. In the summer of 1794, a rebellion over taxes on whiskey erupted in Western Pennsylvania. After attempting to negotiate a peaceful solution, Washington called up the militias from Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and New Jersey to subdue the insurrection. At the end of September, Washington rode out to Carlisle, Pa., to greet the gathering militia.

On Oct. 9, the militia embarked on its journey over the Allegheny Mountains. Instead of leading the troops, Washington turned back toward Philadelphia. A savvy politician, Washington understood that it would be bad optics to have the president marching on his own people. Washington also objected to the principle of the president leading troops into a potential battle. As a civilian leader, his role was to shape strategy, not to lead the army in actual fighting.

Since Washington's retirement in 1797, other presidents have followed his example. Presidents have dictated policy when the army, navy and militias have been called into service, as authorized by the Constitution. But no president has led troops into battle while in office, and they have carefully preserved the distinction between civilian and military authority.

Presidents have attended military parades to mark the end of wars--the Civil War, World War II and the Gulf War. The point of these parades, however, is to commemorate the end of the conflict, troops returning home or the success of an operation. The parades are not designed to celebrate the president as the commander-in-chief.

Trump's proposed parade would break with this custom. Trump did not request his parade to cheer troops safely finishing a deployment or the end of a long, dangerous war. This parade would be a show of ego and military force. This request strikes many as especially egregious given that the president has actively avoided military service. But the real issue is the blurring of military and civilian leadership. Gratuitous parades to celebrate military force belong in dictatorships.

Washington demonstrated that military parades do not belong in republics led by civilians. Of the many precedents he established, this one is often most overlooked, but it is an example worth following.

Lindsay M. Chervinsky is a historian and postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University.

Editorial on 04/29/2018