John McCain, who climbed to the pinnacles of power as a Republican congressman, senator and two-time contender for the presidency, died Saturday at his home in Arizona. He was 81.

McCain died at 4:28 p.m. Mountain time, according to a statement released by his office. He had a malignant brain tumor, called a glioblastoma, for which he had been treated periodically with radiation and chemotherapy since its discovery in 2017.

McCain, with his irascible grin and Navy fighter-pilot moxie, was an outspoken voice on policy and politics to the end, unswerving in his defense of democratic values and unflinching in his criticism of his fellow Republican, President Donald Trump. He was elected to the Senate from Arizona six times but was twice thwarted in seeking the presidency.

A son and grandson of four-star admirals, McCain carried that legacy into battle and into political fights for more than a half-century. It was an odyssey driven by ambition, the conservative instincts of a shrewd military man, a rebelliousness evident since childhood and a temper that sometimes bordered on explosiveness.

As a Navy lieutenant commander, he spent 5½ years as a captive during the Vietnam War after his plane was shot down over Hanoi. He suffered broken arms and a shattered leg, and during his captivity, he was subjected to solitary confinement for two years and beaten frequently.

Often he was suspended by ropes with his arms lashed behind him. He attempted suicide twice. His weight fell to 105 pounds. He rejected early release to preserve his honor and to avoid an enemy propaganda coup or risk demoralizing his fellow prisoners.

He finally cracked under torture and signed a "confession." No one believed it, although he felt the burden of betraying his country.

To millions of Americans, McCain was the embodiment of courage: a war hero who came home on crutches, psychologically scarred and broken in body, but not in spirit.

McCain's death prompted an outpouring of tributes. Trump tweeted Saturday night: "My deepest sympathies and respect go out to the family of Senator John McCain. Our hearts and prayers are with you!"

Past presidents, former political rivals and McCain's Senate colleagues, Republicans and Democrats, hailed the late senator.

"Few of us have been tested the way John once was, or required to show the kind of courage that he did," former President Barack Obama said in a statement. "But all of us can aspire to the courage to put the greater good above our own. At John's best, he showed us what that means."

"John McCain was a man of deep conviction and a patriot of the highest order," said former President George W. Bush.

"Senator John McCain believed that every citizen has a responsibility to make something of the freedoms given by our Constitution, and from his heroic service in the Navy to his 35 years in Congress, he lived by his creed every day," said former President Bill Clinton and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in a statement.

McCain's rival for the Republican nomination in the 2008 presidential race, Mitt Romney, said, "John McCain defined a life of honor."

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said in a statement: "In an era filled with cynicism about national unity and public service, John McCain's life shone as a bright example. He showed us that boundless patriotism and self-sacrifice are not outdated concepts or clichés, but the building blocks of an extraordinary American life."

A MILITARY FAMILY

John Sidney McCain III was born on Aug. 29, 1936, at the Coco Solo Naval Air Station in the Panama Canal Zone, one of many posts where his father, John Sidney McCain Jr., served. He was the middle of three children. His mother, born Roberta Wright, was a California oil heiress.

Whipsawed by family relocations, John attended some 20 schools before finally settling into Episcopal High School, an all-white, all-boys boarding school in Alexandria, Va., in the fall of 1951 for his last three years of secondary education.

But the scion of one of the Navy's most illustrious families was defiant and unruly. He mocked the dress code by wearing dirty bluejeans. He was cocky and combative.

He graduated in 1954 and followed his father and grandfather into the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. In 1958, he graduated 894th in his class, fifth from the bottom.

In 1965, McCain married Carol Shepp, a model. He adopted her two children, Douglas and Andrew, and they had a daughter, Sidney. After a long separation, the couple divorced in 1980. He then married Cindy Lou Hensley, a Phoenix teacher. They had two sons, John IV and James, and a daughter, Meghan, and adopted a girl, Bridget, from a Bangladeshi orphanage.

Promoted to lieutenant commander in early 1967, McCain requested combat duty and was assigned to the aircraft carrier Forrestal, operating in the Gulf of Tonkin. Its A-4E Skyhawk warplanes were bombing North Vietnam.

On Oct. 26, 1967, he took off from the USS Oriskany on his 23rd mission of the war, part of a 20-plane attack on a heavily defended power plant in central Hanoi. Moments after releasing his bombs on target, as he pulled out of his dive, a Soviet-made surface-to-air missile sheared off the right wing of his plane.

He ejected as the plane plunged, but hit something as he exited. Both arms were broken, and his right knee was shattered. He fell into a lake. Swimmers dragged him ashore, where he was set upon by a mob.

McCain was stripped to his skivvies, kicked and spat upon, then bayoneted in the left ankle and groin. A North Vietnamese soldier struck him with his rifle butt, breaking McCain's shoulder. Carried to a truck, McCain was driven to Hoa Lo, a prison compound that American prisoners of war had labeled the Hanoi Hilton.

Only after his captors learned that his father was an admiral was he given a modicum of medical treatment.

Years after his confession to "war crimes" and "air piracy," McCain wrote: "I had learned what we all learned over there: that every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine."

Even then, though, McCain refused to make an audio recording of his confession and used stilted written language to signal that he had signed the confession under duress. And, to the end of his captivity, he continued to exasperate his captors with his defiance.

Throughout, McCain shouted obscenities at guards to bolster the spirits of fellow captives. Appointed by the POWs to act as camp entertainment officer, chaplain and communications chief, McCain imparted comic relief, literary tutorials, news of the day, even religious sustenance.

Bud Day, a former cellmate and Medal of Honor winner, said McCain's POW experience "took some great iron and turned him into steel."

His ordeal finally ended on March 14, 1973, two months after the Paris Peace Accords ended U.S. involvement in the Vietnam war.

LIFE IN POLITICS

McCain's mother inspired his political career. After retiring from the Navy and settling in Arizona, McCain won two terms in the House of Representatives, serving from 1983-87, and six terms in the Senate. He started political service as a Reagan Republican, but later moved right or left, become a maverick who at times defied his party's leaders and compromised with Democrats.

He lost the 2000 Republican presidential nomination to George W. Bush, who went on to win the White House.

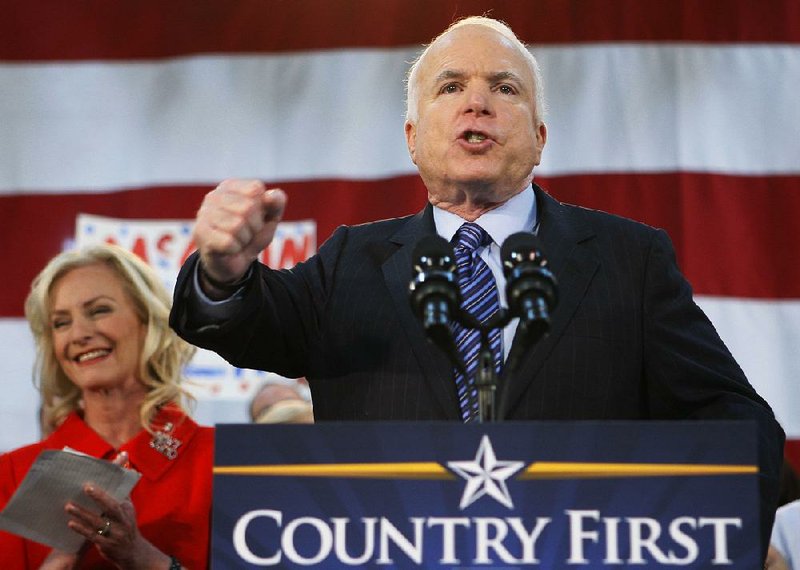

In 2008, against the backdrop of a growing financial crisis, McCain again sought the presidency, this time against the first major-party black nominee, Barack Obama.

With national name recognition, a record for campaign finance overhauls and a reputation for candor, McCain won a series of primary elections and captured the Republican nomination.

But his selection of Gov. Sarah Palin of Alaska as his running mate, although intended to be seen as a bold, unconventional move in keeping with his maverick reputation, proved to be a handicap.

In a 2018 memoir, The Restless Wave: Good Times, Just Causes, Great Fights and Other Appreciations, he defended Palin's campaign performance but expressed regret that he had not instead chosen Sen. Joseph Lieberman, a Democrat-turned-independent.

During some McCain campaign rallies in 2008, vitriolic crowds disparaged black people and Muslims, and when a woman said she did not trust Obama because "he's an Arab," McCain replied: "No, ma'am. He's a decent family man, a citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues."

On Election Day, McCain lost most of the battleground states and some that were traditionally Republican.

As Congress reconvened in January 2015 with Republicans in control of the Senate, McCain achieved his longtime goal to become chairman of the Armed Services Committee. He considered the post second only to occupying the White House as commander in chief.

McCain embraced his role as chairman, pushing for aggressive U.S. military intervention overseas and was eager to contribute to "defeating the forces of radical Islam that want to destroy America."

One dramatic vote he cast in the twilight of his career was in 2017 when he voted "no" on Senate GOP legislation to repeal the Affordable Care Act. McCain became the unlikely savior of Obama's trademark legislative achievement.

With Trump's election in 2016 as the nation's 45th president, McCain was one of the few powerful Republican voices in Congress to push back against Trump.

Personal animus between McCain and Trump arose in the Republican presidential primaries in 2016. McCain and Mitt Romney, with standing as the previous two Republican presidential nominees, denounced Trump as unfit for the presidency.

In response, Trump denigrated Romney as a "failed candidate" and "a loser" beaten by Obama. He had little to say about McCain. But months earlier, Trump, who had never served in the military, derided McCain as a bogus war hero and made light of his years of captivity and torture.

"He's a war hero because he was captured," Trump said. "I like people who weren't captured."

McCain declared the comment offensive to veterans, but urged them to "put it behind us and move forward."

Information for this article was contributed by Robert D. McFadden of The New York Times; by Nancy Benac and staff members of The Associated Press; and by staff members of The Washington Post.

A Section on 08/26/2018