When they lay that medal on your crooked heart

Cast your eyes to the heavens in the name of art

-- Amy Rigby, "From Philip Roth to R. Zimmerman"

For most of us, prizes mean nothing.

Maybe if you're in a certain sort of occupation, you know about competition. Maybe there's a big board up on the wall in your office and if your name stays at the top of it for long enough -- if you sell enough units or generate enough clicks -- you get a new Cadillac. If you're No. 2, maybe a set of steak knives. For most of us, the prize is we get to keep our jobs.

But it's not that way for everybody. If they give out awards in whatever business you're in, you probably understand that there are a lot of factors that determine whose name gets engraved where, and that merit is rarely the most important of these factors. In my business, we give each other a lot of awards, and we're all pretty cynical about them. They're nice to win, but if you don't win, you can always point to the undeniable and inherent subjectivity of the contest. Most awards are more about the judges than the recipient.

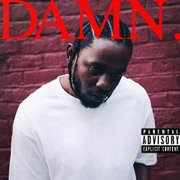

And so Kendrick Lamar has won a Pulitzer Prize for music for his album Damn., marking the first win for a nonclassical or jazz musician since the awards began including music some 75 years ago. Those inclined to be outraged by a 30-year-old hip-hop musician capturing a prize that Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen have never won were quick to accuse the Pulitzer jury and the board of using the prize to advertise their "wokeness." Others celebrate Lamar's Pulitzer as a signal that rap music (and all the black culture it interpolates) has somehow been "legitimized."

Most of us might agree the real significance of Damn.'s win is that it's an opportunity to examine the album in a broader context than as the commercial product in which most hip-hop albums are considered. A Pulitzer suggests some aesthetic value beyond mere entertainment, and anyone who has listened to Lamar's music can confirm that the rapper is an artist who aspires to connect at a level deeper than most pop singers. His compositions have sonic complexities, his best lyrics engage political and philosophical questions about how we are to live in the world. Lamar uses the 55-minute running time of Damn. to call out the hypocrites and limn the still real struggles of blackness in 21st-century America.

The short intro "Blood" (all the track names as well as the album title are typographically stylized as capitalized and punctuated by a period, as in "BLOOD." and DAMN.) begins with Damn.'s producer Bekon (a hip-hop journeyman whose real name is Daniel Tannebaum and who as Danny Keyz has collaborated with Eminem, Snoop Dogg and Aloe Blac) singing "Is it wickedness? Is it weakness? You decide, are we going to live or die" in a highly processed, eerie voice-over an instrumental track that wouldn't feel out of place in a Dramatics ballad from the '70s.

Then Lamar picks up the story, talking about how he stops to help a blind woman on the streets of Compton. There's a gunshot -- blam -- and he's down or dead, our guide to the underworld. And we hear the voices of Fox News personalities criticizing Lamar's performance on the 2016 Grammy Awards.

This could seem silly, or score-settling, but the Pulitzer board's description of Damn. as "a virtuosic song collection, unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African-American life" is a pretty good summation. Obviously Lamar's cultural significance played into his receiving the award, but Damn. -- contrary to what some critics have suggested -- is not just another Kendrick Lamar album. It demonstrates significant artistic evolution.

. . .

Lamar's 2012 major-label debut Good Kid, M.A.A.D City was a great debut, but it was a young man's record, an autobiographical "Hello, World" moment that, as was the professional debut of Tiger Woods in 1996, might in retrospect be taken more as an announcement of promise than authentic accomplishment. To an extent the outsized hooks and infectious beats obscured a certain lyrical grittiness. If you wanted, you could minimize the political content and take Lamar as a crossover rapper, a kind of SoCal Drake.

And 2015's To Pimp a Butterfly was an audacious display of range, a demonstration of the artist's mastery of traditional soul, jazz and funk styles married to thoughtful, self-aware and explicit ruminations on the nature of American fame and celebrity. It was widely seen as one of the landmarks of the genre, and Lamar was hailed in some quarters as not only the greatest rapper alive, but as one of the signal voices of black America and -- with others like Kanye West, content to self-caricature themselves as consumerist capitalists and Twitter winners -- the only rapper who mattered to casual and nonfans and those looking for cultural champions to stand for more than self-aggrandization and dazzling bling.

Under those conditions, you might expect the next album to be a retreat. Seen through a certain prism, that's exactly what Damn. is -- it has little of the jubilant spirit of To Pimp a Butterfly, settling into a darker, more direct key. It's not as hopeful as his previous work; it feels resigned and serious. It's a political album, an indictment of a regressive America where black lives matter less than the grievances of the powerful. That's not to say it's better than Lamar's previous work, only that it's more mature, and that it occupies a central place in a turning zeitgeist -- Damn. is of a piece with movies like Barry Jenkins' Moonlight, Ryan Coogler's Black Panther (a movie for which Lamar produced the soundtrack), Jordan Peele's Get Out, and Beyonce's visual album Lemonade.

As much as it is a startling record, it's also -- to evoke another black artist who never won a Pulitzer -- a sign of the times.

. . .

Still, there have been plenty of other moments; Smokey Robinson or Stevie Wonder might have been good choices a few decades ago. But conventions are hard to overcome. Pulitzers are like Oscars in that there are -- or have been -- certain kinds of work that are considered, certain kinds that win. The perspective of the gatekeepers in never genuinely wide.

There are plenty of people who will never accept the legitimacy of hip-hop as anything other than a novelty and plenty of musicians who, though they may enjoy the genre, might argue against Lamar's Pulitzer on the grounds that the awarding of this particular prize to a rich and famous rapper means that some worthy classical or jazz musician toiling in relative obscurity misses out.

"Even those composers and critics who like rap as music, and accept the political inevitability of its claims to be art, worry that the unique perspective of the Pulitzer in Music is being lost," UCLA professor of musicology Robert Fink wrote on the university's website last week. "What they valued about the prize was not that the juries always hit the bulls-eye of 'greatness' -- many serious compositions have won a Pulitzer only to sink back into deserved obscurity, and many of the most important composers of the modern era (Cage, Glass) never won one -- but the way the Pulitzer Prize focused attention, if only for a moment, once a year, on a particular kind of music that was uniquely eligible to be great: elaborate concert music in the Western tradition composed by individuals and scored for traditional ensembles of (mostly) acoustic instruments.

"Of course, most people don't listen to that type of music, especially brand-new pieces in that vein written in America during the previous 12 months. This is precisely the point: One of the most succinct definitions of 'classical' music is music that most people don't listen to, but which more or less everyone agrees is paradigmatic Music-with-a-capital-M.

"In this sense, the Pulitzer does not index popularity, it indexes hegemony. As long as the Prize was reserved for some kind of 'classical music,' even modern classical, or black classical (jazz), then classicism in music, the idea that there is a canon of great works that sets the tone for the whole world of music -- even in absentia, even if no one but a small cadre of 'experts' actually listens to it -- could be preserved. That's why a number of classical music apologists complained that they had nothing against Kendrick Lamar personally except that everyone already knew who he was. His music was genuinely popular, and so making it canonical, too, seemed unfair, over the top, like giving an honorary doctorate to a billionaire."

Fink went on to say "this hegemonic idea of 'classical music' is dying, and I, for one, am not shedding any musicological tears over that. "

. . .

Lamar's Pulitzer is likely to have little effect on his life or lifestyle.

Although it might invite a few people who are curious about his work to download or stream Damn., the larger effect is to advertise the board's hipness. On the other hand, nobody should think that awards actually confer what they are purported to convey -- black style has long been the dominant gene in America's cultural DNA. It's an important part of rock 'n' roll and jazz and even in a certain risk-taking jazz-influenced athletic style that predominates in world class sports. (Jackie Robinson and Elvis Presley changed the world more than any other 20th-century Americans.)

Rap music needed a Pulitzer like rock 'n' roll needed a Hall of Fame, which is to say not at all. Lamar's Pulitzer is something for talk-show hosts and columnists to debate, something upon which we might hang a phony conversation. You can think it's nice, but it doesn't do anything. Bob Dylan didn't need the validation of a Nobel Prize, and when that validation showed up at his door unannounced it's no wonder it took him a little while to figure out how to respond. He didn't become Bob Dylan to win Nobel Prizes, he did it to meet girls.

My friends who think they hate rap music are not going to start listening to Damn. simply because Lamar has won a Pulitzer Prize, they're not going to move off their "it's-not-music" position because the authorities have deemed it so. And that's fine, because everybody misses out on something because of ignorance. And there's no winning the semantic argument over what music is with anyone -- music is personal. It's fine not to like what what you don't like and it's boring to argue otherwise.

Still, I'm all for opening hearts and ears, and don't know that an honest listener can hear Damn. and dismiss it as unworthy of sincere consideration. It is a remarkable document, an assemblage of sound and noise and whispers and screams that adds up. I understand why it speaks across generations and classes and races, why artists such as Jason Isbell and Steve Earle have professed admiration for Lamar.

One of the most encouraging things about America is that, even in dirt-road rural counties, you're just about as likely to hear Kendrick Lamar blasted from the dashboards of the cars of 17-year-old white kids as you are Jason Aldean.

And that's something.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangles.com

Style on 05/06/2018