WASHINGTON -- Federal Reserve officials were sharply divided last month when they decided to cut their key policy rate for a second time this year, a split that indicates the path forward for future rate cuts remains cloudy.

Minutes of the discussion at the September meeting released Wednesday showed that the majority of Fed officials believed a second quarter-point cut was appropriate given increased economic uncertainty from trade tensions and a slowing global economy.

However, a "couple" of participants indicated they favored a half-point reduction. They said the larger rate cut would reduce the risks of a possible recession.

But a third group of "several participants" argued that the Fed should not be cutting rates at all, saying that the current outlook for the economy had changed little since the central bank's last meeting.

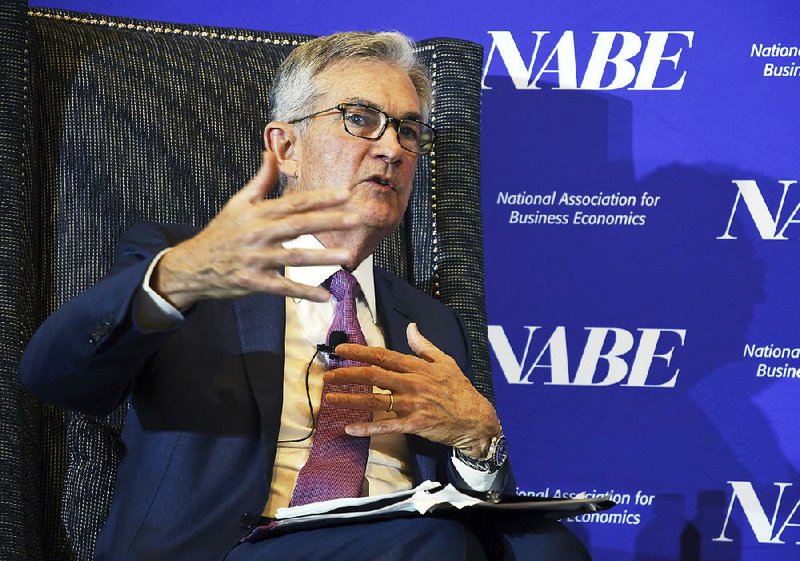

This rare three-way split on the Fed's top policy panel indicates that Fed Chairman Jerome Powell may face challenges in reaching consensus on future moves on rates.

Many investors are hoping the Fed will cut rates for a third time this year when it meets again at the end of this month.

The September rate cut, which followed a cut in July that was the first in a decade, was approved on a 7-3 vote. Two Fed officials, Esther George, president of the Fed's Kansas City regional bank, and Eric Rosengren, president of the Boston bank, dissented in favor of no cut.

James Bullard, president of the St. Louis regional bank, dissented in the other direction, arguing that the threats to the economy were large enough that a bigger cut was needed.

The minutes however showed that there were other Fed officials who disagreed over the quarter-point rate cut although not strongly enough to dissent.

Policymakers at the September meeting expected the economy to continue growing steadily with the help of their rate cuts, the minutes showed. But they were increasingly worried about risks to that outlook from President Donald Trump's trade war, the threat of a chaotic British exit from the European Union and protests in Hong Kong.

"Participants generally had become more concerned about risks associated with trade tensions and adverse developments in the geopolitical and global economic spheres," according to the minutes. "Several participants mentioned that uncertainties in the business outlook and sustained weak investment could eventually lead to slower hiring, which, in turn, could damp the growth of income and consumption."

The Federal Reserve has two main tasks: promoting maximum employment and maintaining stable inflation, which it defines as 2% annual price gains. To achieve those goals, policymakers adjust interest rates to try to keep the economy growing at a steady and sustainable pace.

The policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee has become increasingly divided over how to achieve those objectives. That is because the economy's prospects have been clouded by the trade war and other uncertainties even as consumer spending and job growth have held up.

Some policymakers favor lowering borrowing costs now to insulate the economy against potential shocks, arguing that changes in monetary policy affect the economy with a big lag. But others want to wait for a more pronounced weakening in the economic data, or worry that lowering rates could fuel financial bubbles.

In remarks this week, Powell has said the Fed will be taking moves to deal with any economic turbulence.

Speaking Tuesday in Denver, Powell said that "policy is never on a preset course and will change as appropriate in response to incoming information."

Despite their generally positive assessment of the current economy, Fed policymakers were attuned to risks other than the trade war when they met last month, the minutes showed.

Several noted that some statistical models suggested that the likelihood of a coming recession "had increased notably in recent months." But a couple of officials stressed that such models were difficult to interpret.

Some were concerned that a prolonged inversion of the yield curve -- a common recession signal in which interest rates on longer-dated bonds fall below those on short-term debt -- could "be a matter of concern." And "several" were concerned about financial stability, citing a buildup of corporate debt, stock buybacks financed with low-cost debt, and rapid lending in the commercial real estate market.

Despite the mounting risks, "a few" Fed officials felt that markets were expecting too many Fed interest rate cuts going forward, "and that it might become necessary for the committee to seek a better alignment."

The minutes showed officials also discussed the turbulence in a short-term funding market called the repo market that occurred in the week the central bank was meeting.

The minutes showed that among the options discussed would be to allow the Fed's balance sheet to grow again. The Fed had been reducing its holdings that had surged to a peak of $4.5 trillion in the wake of the recent recession as it engaged in several rounds of bond purchases aimed at lowering long-term rates and giving the economy a boost.

Those bond purchases were known as "quantitative easing." Powell said that while various options were being weighed for providing more stability for the short-term funding markets, the effort should not be considered a new round of quantitative easing.

Information for this article was contributed by Martin Crutsinger and Christopher Rugaber of The Associated Press and by Jeanna Smialek of The New York Times.

Business on 10/10/2019