Thirty years ago, a movie about the Mafia became a classic because it did what mobsters do: It broke the rules.

While most of the movies about gangsters like "Scarface" (both the 1932 and 1983 versions), "The Godfather," "The Untouchables" and "Little Caesar" deal with dons or criminals who come close to running the underworld, Martin Scorsese's "Goodfellas" focuses on Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), a career crook never destined to rule Cosa Nostra.

Despite having a Sicilian mother, Hill's Irish blood prevented him from becoming a made man.

"Goodfellas" is about a nobody. Nicholas Pileggi, who wrote the 1985 book "Wise Guy: Life in a Mafia Family" and earned an Oscar nomination for adapting it for the screen with Scorsese, intended it that way.

"There had been several books, really good ones about mob bosses," Pileggi says, by phone from New York City. "There's several about Al Capone and Joe Bonanno. But they were always about the boss. I thought, just to change the deal a little bit to get a guy who was not a boss, but a worker, a soldier or lower than a capo, and I just felt that that would get you closer to the bone ... I thought you'd be able to see what life was like if you're not a superboss. I think it would be more revealing. It was fresher for me as a reporter."

The writer compares it to profiling a soldier in the French Army instead of Napoleon himself. "He's the one who was cold, not Napoleon," Pileggi explains.

No Average Nobody

Hill normally wouldn't have discussed his life in crime, but as "Wise Guy" came into being, he was under witness protection for testifying against his former cohorts and needed the cash from a book deal. He had violated the code of omerta ("Never rat on your friends, and always keep your big mouth shut").

Hill may not have been a leader, but he also wasn't a typical mobster. He had taken a community college class in restaurant management and was an accomplished cook. He'd also served in the U.S. Army. Despite the frequent profanity, he didn't speak like a wise guy, either.

"A lot of these guys, you can have them on tape for hours and hours, and they don't say anything," Pileggi says. "They're very monosyllabic. They don't give you color. You need somebody who can tell you a story. A lot of these guys have spent their entire lives not telling stories. When they sit down with an author, they're not very good at it. They're good at being gangsters, but they're not very good at telling stories.

"Henry was the exact opposite. Henry was a great storyteller, and he had attention to detail. He'd remember the color of a car from 40 years ago."

It also helped that Pileggi, now 87, had covered crime for The Associated Press for nearly 16 years.

"In conversation with me, he was talking about Johnny Wagonwheels. I said, 'Oh, you mean Johnny Fatico.' I'd been covering all this since the '50s. He said, 'Let's do it.' The reason, I found out later, was if I knew who Wagonwheels was, then he wouldn't have to explain it to me. It would make life easier for him."

No Star Treatment

Pileggi covered the New York underworld, as well as incidents like the sinking of the Andrea Doria, but you might not know it from reading his articles. Unlike his cousin, New Journalism pioneer Gay Talese ("Frank Sinatra Has a Cold"), fame is something relatively new in Pileggi's career.

"I was covering stories in New York about the Mob, but it would go out as a story by The Associated Press. In 15 or 16 years, if I had three bylines, it was a lot. And I covered big stories," he recalls. "Usually the star AP guy got the byline. I didn't care. I loved the AP. I still do. I didn't need the recognition that went in that direction. The fact that I was not well known [was] helpful for me on the street. Guys could not pick up the (New York) Daily News and see my name on a story about some wise guy. That person might not want to talk to me."

In addition, "Wise Guy" and "Goodfellas" feature the perspective of Hill's wife Karen (Oscar-nominee Lorraine Bracco), who divorced him in 1989. In the predominantly male world of the Mob, Karen's participation gave a new depth of understanding to what life in the Mafia was like. While the idealized depiction in "The Godfather" (at least in the first movie) makes for great drama, it didn't square with what happened when she married into the Mob.

"When I met her, I thought it would be good to have the wife of a gangster," Pileggi says. "You find out [gangsters] don't know anyone else. They'd go on vacations together. The insularity of that world, I didn't know about it, until I met Henry. There are no strangers."

Narrative Cheats

In depicting Henry Hill's world honestly, Pileggi and Scorsese also abandoned the timeworn trope of depicting mob violence as often a matter of honor. Whereas the Corleone family in all three "Godfather" movies is trying to gain redemption, Hill and his associates have a more mundane reason for being involved in crime.

"It's a money-oriented world, and that's why they're all in it. That's why they're taking such a chance," Pileggi says.

Even as he and Scorsese were adapting the book, the two may have taken much of the text straight from Hill's quotes in the book, but a technique Scorsese refined with his previous movies like "Taxi Driver" helped keep "Goodfellas" startling: Often the images and the pictures deliberately don't match.

"[Scorsese] said, if you see something, the voiceover should be saying something else," Pileggi says. "You don't want to show people the same thing twice. For instance, when [Hill, played as a teenager by Christopher Serrone] lights the fire in those cars and then runs across the street. The last thing he has to say is, 'I lit fires, and I threw in gasoline.'

"'No,' Marty said, 'let's use different voiceover. You know about how the guys used to carry my mother's groceries home and that I didn't have to wait on line. It gives the audience a double whammy. You see a visual, and then the voice-over is giving you more."

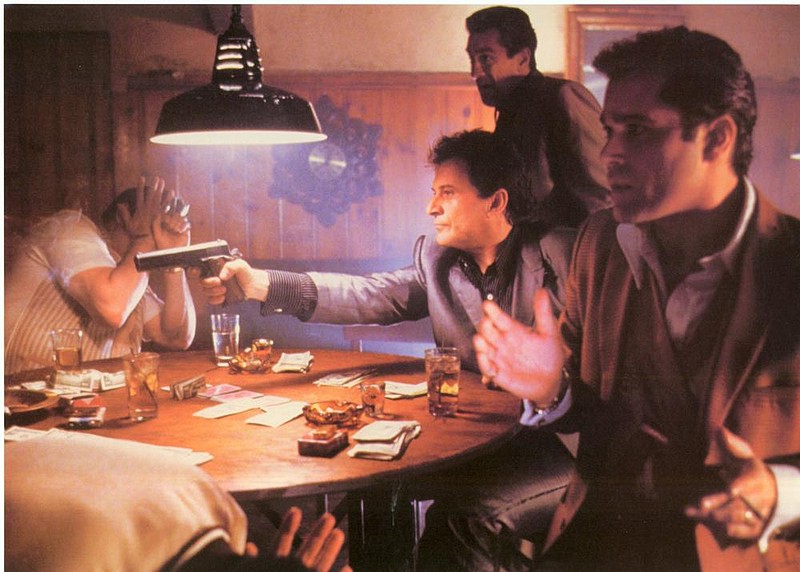

Another convention that the two screenwriters abandoned was depicting the Lufthansa terminal heist and New York's JFK airport on Dec. 11, 1978. While Hill's associates Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) and Jimmy "The Gent" Conway (Robert De Niro) were involved in stealing $6 million, we only see Hill's reaction in the shower. It made heist-free heist movies like Quentin Tarantino's "Reservoir Dogs" possible.

"The real world dictates your story," Pileggi says. "If you give time to figure it out, it's often much better than anything you could ever make up. Normally, Henry is the movie star. It's Ray Liotta's part. Lufthansa is the thing that's going to make them, and you see the stickup. We see nothing. All you see is Henry in the shower. You have the [radio] news broadcast. That's all you need. It's the aftermath that you need, not the stickup."

"Goodfellas" more than doubled its $20 million dollar budget and earned Pesci an Oscar. More importantly, the film has had a long shelf life and has gone on to influence legions of other movies and TV shows. David Chase, the creator of "The Sopranos," calls "Goodfellas," "my Koran."

The Internet Movie Database also lists "Goodfellas" as the 17th best film ever made.

The Mob by the Book

Glenn Kenny, a critic for The New York Times and RogerEbert.com, has written about the impact of the movie and how it was put together. "Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas" also recounts Henry Hill's life after "Goodfellas" ends in 1980. It explains where the film, while remarkably faithful to Pileggi's nonfiction book, differs from Hill's life.

"It's a substantial piece of work, and I hope I did it justice for sure," says Kenny from Brooklyn. "Scorsese ... when I interviewed him in 1989 ... [when] he was editing 'Goodfellas' ... said, 'Even if this movie comes in at 2½ hours, I still hope it's one of the fastest-paced movies ever. It's a movie that sort of lifts you up by the scruff of the neck and brings you along for what they call a wild ride.'

"The movie gives you the very heady feel of what it's like to be part of that world," Kenny says. "Americans have always been fascinated by gangsters. In a way, Scorsese is asking why he's fascinated by gangsters."

Critics at the time shared Kenny's enthusiasm for the movie.

Curiously, as "Made Men" documents, the movie had trouble reaching theaters. Preview audiences in Orange County, Calif., walked out in droves. Pileggi recalls 31 people leaving. Warner Bros., which has since issued several deluxe DVD and Blu-Ray editions, was also uncomfortable with Scorsese and Pileggi's unflinching vision of the Mafia.

While the audience with me in Little Rock's now-defunct Market Street Cinema laughed hysterically as the teenage Hill survives his first arrest without squealing on his fellow gangsters, Kenny says we almost missed our chance to enjoy the movie.

"The violence, in particular, made people very nervous," Kenny says. "That feeling of nervousness was exacerbated by the previews in California. People were calling, 'Bring us Scorsese,' calling for his head. They were mollified when the actual reviews came in, and it was 90% ecstatic.

"It helped them at the box office. It gave them the same idea that they could apply the same principle to marketing our big holiday film, which turned out to be the Brian De Palma adaptation of 'Tom Wolfe's 'The Bonfire of the Vanities.' The only problem with that scheme was that 'The Bonfire of the Vanities' did not get the same caliber of reviews."

Cooking the Books

"Made Men" even includes the complex recipe Hill cooked at the climax of the film. Apparently, multitasking great Italian cuisine, illegal arms sales, narcotics trafficking, cocaine usage, mistresses and a hospital visit was just a little too much for Hill or anyone else to handle.

If you don't wish to go to jail or end up with the Mob's permanent severance package, cooking the recipe may be the only moral aspect of Hill's life.

"You've got to stir it for four hours," admits Kenny. "My wife said it was life changing."

Sadly, "Made Men" documents how leaving the Mafia did little to curb Hill's substance abuse problems. The film documents some of his transgressions as a husband, but the new book indicates Hill could be even worse to the people around him. That probably contributed to his relatively young death at age 69 in 2012.

"He's a bad husband in the film, and he was a worse husband in real life, especially after going into the witness protection program and coming out of the witness protection program. Henry Hill's kids Greg and Gina wrote a very revealing and depressing book called 'On the Run,' which didn't even go up until after the movie came out. It was about what an alcoholic, cocaine abusing, wife-abusing guy he was," Kenny says. "Because he ratted out his only friends, he was trying to figure out a life for himself in this context, and he became worse. He'd try to get sober, have some success, and then he would call up Howard Stern when he fell off the wagon."

A Mother's Brush

While "Goodfellas" may be a great film, it was neither Scorsese's movie, nor the studio's, according to Pileggi's late mother. "Goodfellas" was her movie.

In the breakfast scene where Catherine Scorsese (the director's mom) plays Joe Pesci's mother, the men in the room try to hide from her that an assaulted gangster is hidden in her trunk. She shows them a painting that Susan Pileggi herself made. Her credit is the last in the film, and her painting is almost as omnipresent as the movie her son co-wrote.

"My son was showing me yesterday. You can kind of go on the computer and find it on coffee mugs and T-shirts. It's just insane," Pileggi says. "I have the original in my office. My [step] son Max [Bernstein] has a lot of friends of his who are [also] musicians. When they realize who his stepfather is, they come to New York, and they want to meet me, and they want to have their picture taken with Max and me and the painting."