LITTLE ROCK -- Albert Pike Elementary School in Fort Smith was built and named in 1952, and the school's website describes its namesake as "a local educator and celebrity."

What isn't mentioned is that Pike also was a Confederate general who joined a petition in 1858 to "expel all free blacks from the State of Arkansas."

In August, the School Board approved unanimously a resolution to adopt a new name for the school and asked the city's residents for suggestions.

On Oct. 12, the board approved a motion to adopt Park Elementary School as the new name and authorized Superintendent Doug Brubaker to make preparations necessary to implement the transition to the new name for the beginning of the 2021-22 school year.

The move is part of a growing trend in Arkansas and elsewhere after nationwide protests this summer regarding race. At issue is whether it's appropriate to publicly honor figures who at one time supported segregation.

Task forces were created earlier this year at Harding University in Searcy and the University of Arkansas to examine racial representation on the campuses after student-led movements called for removal of the names of those who held racist ideals from campus buildings.

Similar efforts in July, led by the University of Central Arkansas' Student Government Association, resulted in university officials removing former Gov. Ben Laney's name from a building on the Conway campus after a petition outlining Laney's racist views drew support from the faculty and staff.

The schools' responses are examples of social movements that have garnered majority support across races, according to the Pew Research Center. Historians also point to it as the latest example of a younger generation clashing with an older generation that wants to hold on to traditions.

Schools, parks, streets, military bases and even cities have become targets of calls for change in the wake of protests after the publicized deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others.

Floyd, a Black man, died May 25 while being restrained by a Minneapolis police officer who pressed his knee into Floyd's neck for almost 9 minutes. Taylor, a Black woman, was shot five times in her Louisville, Ky., apartment March 13 by officers carrying out a narcotics warrant. The warrant was related to an investigation of a drug suspect who didn't live with her, and police found no drugs at Taylor's apartment.

Those incidents and others inspired a younger generation of protesters to take to the streets and campuses demanding change.

"My generation in the '60s were young when we fought for a better world," said Nan Elizabeth Woodruff, a professor of African American studies at Penn State University. "In moments of crisis, young people come forward."

A 2019 Southern Poverty Law Center study counted 103 public K-12 schools and three colleges across the nation named after Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis or other Confederate figures. A combined 80 counties and cities, as well as 10 U.S. military bases, were named after Confederate figures, according to the study.

Many schools, parks and streets were named after Confederate figures during a period when there was resistance to equality for Black people, the study noted.

In June, an Education Week analysis of federal data found that at least 211 schools in 18 states were named after men with ties to the Confederacy. Since June 29, 10 of those schools have changed their names, the article stated.

Six schools in Arkansas are named after Confederate generals, according to an Education Week article from September. They are Albert Pike Elementary School in Fort Smith, the junior and high schools in the Forrest City School District, Lee High School in Lee County, Forrest Park Prep Preschool in Pine Bluff and Robert E. Lee Elementary School in Springdale.

Alice Guchuzo-Colin, a Black woman, lived for more than 20 years in Springdale, where she helped organize the city's Martin Luther King Jr. parade before moving this summer to New York. She said she lived in the Lee Elementary district but drove her children to another school because she didn't want them attending a school named after Robert E. Lee.

"I couldn't send my children who are half Black and half Mexican to a school that pays homage to a man that wanted to keep someone as property," Guchuzo-Colin said. "It pays homage to pure hate."

The Education Week study noted countless other schools nationwide that bear the names of individuals with "racist histories," including 22 named after politicians who opposed school integration.

The study listed four Arkansas schools named after politicians who in 1956 signed the Southern Manifesto, which opposed racial integration in public places. Those schools are Fulbright Elementary School, McClellan Magnet High School and Wilbur D. Mills High School, all in Little Rock; and J. William Fulbright Junior High School in Bentonville.

Research done by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette found that at least three Arkansas counties and two cities are named after Confederate generals, and at least 11 streets in the state bear the names of Confederate leaders.

'MOMENT OF REFLECTION'

Fort Smith's School Board released a survey in September after approving a resolution expressing its intention to adopt a new name for Albert Pike Elementary.

The resolution directed the school district administration to organize a committee to develop and recommend a renaming process that involved stakeholders from the school community.

The resolution stated that Pike joined a petition in 1858 to "expel all free blacks from the State of Arkansas." He also wrote in 1868 that "We mean that the white race, and that race alone, shall govern this country. It is the only one that is fit to govern, and it is the only one that shall."

Members of the district's equity and minority recruitment committees discussed the school's name in July and recommended to the board that the school be renamed.

The auditorium at Harding University in Searcy bears the name of George S. Benson, who is credited with pulling the school out of debt during his tenure as the college's second president, but also spoke against Harding College's integration in the late 1950s.

Students and other Harding community members are now questioning whether it's appropriate to have an auditorium -- where university students are required to attend chapel every day -- named after a man who opposed integration of the school.

A petition started in June seeks to rename the auditorium after Botham Jean, a Black alumnus who was murdered in 2018 by a police officer in Dallas. It had nearly 18,500 signatures as of this month but the university's president, Bruce McLarty, remains steadfast in support of keeping Benson's name on the auditorium. Instead, McLarty has said the university will add language that will provide a more complete account of Benson's legacy.

"My first impression was that the divide among these opinions was because of age; a large majority of those who favor removing the Benson name are current or recent students, while a large majority of those who favor keeping the Benson name on the building are above the age of fifty," McLarty said in a June post that expressed an unwillingness to rename the auditorium.

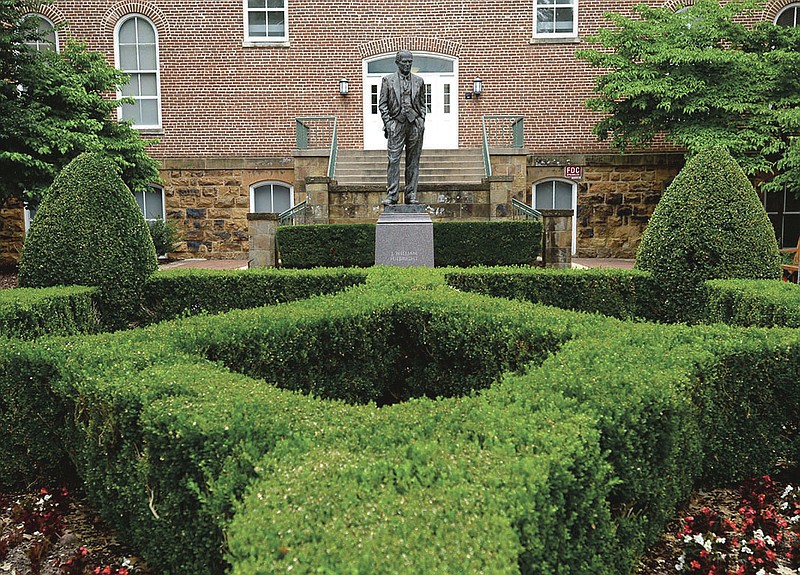

Students and alumni at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville also added their names to a petition requesting that former U.S. Sen. William Fulbright's name be removed from the university's arts and sciences college, which was named after Fulbright in 1981. The petition also seeks the removal of a Fulbright statue from campus.

Black student leaders criticized Fulbright's record on civil rights, part of a wave of social media posts regarding racial biases and inequity experienced on campus.

"Oftentimes, diversity and inclusivity are cloaked, skeletal terms that never truly result in tranquility and happiness for the very group it is supposed to be including," the Black Student Caucus said in a statement posted on social media. "We seek happiness, wholeness, and fulfillment for Black students at the University of Arkansas."

UCA's Student Government Association sent out a petition asking students and alumni to support an initiative to remove Laney's name from Laney-Manion Hall.

"Governor Laney was a frequent opponent of civil rights and anti-segregation legislation," the petition states, quoting past Arkansas Gazette articles. "Governor Laney was so opposed to President Truman's civil rights proposals that he was a leader in the segregationist 'Dixiecrat' movement of 1948."

Jennifer Cale, the student government's vice president of finance, said the name change was discussed two years ago but didn't gain traction. It was brought up again this summer in the wake of the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement.

Built in 1994, Laney-Manion Hall houses the Department of Chemistry and is built on the site of the original Laney Hall, named after the former governor. In 2014, it was renamed Laney-Manion Hall in recognition of Jerald "Jerry" M. Manion's service to the university. Manion spent nearly 50 years at UCA as a professor, mentor and ambassador for the chemistry department.

Jamaal Locking, a Black student and executive vice president for the student association, said having Laney's name on the building makes it unwelcoming for people of color.

"If one of our university's core values is diversity, then we shouldn't have a building named after someone who worked to ensure higher education was segregated and away from people of color," Locking said.

Locking said his generation understands the history of systemic racism.

"We aren't blaming people for the past, but we are asking people to recognize how it has impacted today," he said. "While these conversations are uncomfortable, our generation isn't afraid to have them."

Such controversies aren't new, said Caroline Janney, a University of Virginia history professor who specializes in Civil War and 19th century U.S. history. Similar calls for change often occur in waves, she noted.

"The first wave was the [Confederate] flags, and that happened when the Olympics came to Atlanta [in 1996]," Janney said. "Then we had another one in the early 2000s, then in 2015 after the Dylan Roof shooting and then Charlottesville."

Woodruff said the most recent push resulted from a social climate that includes a global pandemic, a rise of right-wing nationalism and activism among younger generations.

"This is a moment of reflection in this country," she said.

HISTORY OF NAMES

History shows that leaders understood the power of symbols, statues and names, Woodruff said.

"The purpose of symbols and monuments are the way people forge national identities," she said. "The white South was trying to resurrect themselves from defeat in the Civil War. These monuments and names were attempts to change the narrative around their failure."

The intent behind the naming of buildings, parks or schools depends on the circumstance, Janney said.

"Some places honor a specific person from the area or a regiment, but naming something after a Confederate general or politician who has no ties to the state can be viewed differently," she said. "It's the same thing as having a monument honoring a specific person compared to a 6-foot grand statue in the middle of Main Street."

Forrest City, in St. Francis County, was named after Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, the general who created a railroad construction commissary there in 1866, according to the Central Arkansas Library System's "Encyclopedia of Arkansas."

Forrest was treated as a Civil War folk hero for many decades, but various cities and states have distanced themselves from the Confederate general because he also was the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan and his history of racially motivated violence.

Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee introduced legislation this year that would amend a law that requires the state to honor Forrest with a day of observation in July. Last year, Memphis renamed Forrest Avenue to Forest Avenue.

Forrest City Mayor Cedric Williams, who is Black, said he believes the majority of residents are aware of the origin of the city's name and that there isn't a need to rehash the past.

The city's estimated population is about 14,044, with 72.3% of it black, according to census data.

Williams said he understands the concern some might have, but he hasn't "officially been approached" by anyone who wants to change the city's name.

Nate Bell, a former state legislator who served three two-year terms in the House of Representatives, starting in 2011, said taking on tradition can be a challenge. Bell was elected as a Republican but became an Independent in 2015.

Bell, 51, clashed with some members of the Republican Party in 2015 over his proposal to end the state's practice of commemorating Robert E. Lee and Martin Luther King Jr. on the same state holiday. The proposal called for removing Lee from the state holiday, and a similar proposal was rejected by his committee.

In 2017, legislation sponsored by Republican Rep. Grant Hodges and Republican Sen. David Wallace was approved that removed Lee from the holiday honoring King, the slain civil rights leader.

"I never realized the pain it brought my African-American friends, and that was the reasoning behind the proposal," Bell said. "I got all kinds of negative reactions. I had people threatening to burn my house down and threatening me and my family."

Bell said he noticed a generational difference regarding the change, noting that his generation and those before him didn't have many "real friendships" across the racial divide.

"We don't know what other cultures love or what hurts them," he said. "My generation and older really have a lot of embedded systemic racism that they don't even recognize."

CHANGES TAKE TIME

Williams, Forrest City mayor, said he would listen if a name change is taken before the City Council, but implementing such a change would be a huge undertaking.

"The economic costs of trying to get that done would be massive," he said. "You are talking about schools, hospitals, businesses all being affected."

Removing names typically takes time as well, which can lead to frustration.

"When McLarty decided to not rename the auditorium, I was (and still am) extremely disappointed and concerned," Erin Weiss, a student who supports changing the auditorium's name at Harding University, said in an email. "I want the Black community at Harding to feel accepted, safe, and heard."

Harding's vice president for university communications and enrollment, Jana Rucker, referred to McLarty's original statement in a response to an interview request and said there was nothing more to add.

"There are strong opinions on both sides of the argument," Rucker said. "We continue to work within the Harding community to implement meaningful change."

Kimberly Mundell, a spokeswoman for the Arkansas Department of Education, said the department hasn't received any requests to rename any schools under state supervision. She said the law that refers to district names requires each school district run by the state to keep its name unless changed by the state Board of Education.

The Little Rock, Earle, Dollarway, Pine Bluff and Lee County school districts are under state authority.

Pamela Smith, spokeswoman for the Little Rock School District, said David O. Dodd Elementary is the only property that has received an inquiry about a name change, but Smith added that this is the last year for Dodd Elementary to be included as a district school site. Students attending the school will transition to the J.A. Fair campus as part of a kindergarten-through-eighth-grade site.

After race riots in Charlottesville in 2017, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette checked in with a number of schools around the state named after figures associated with the Confederacy and found that there had been little call for change.

Springdale Public School officials said there had been "a minimal number" of complaints in 2017 about the name of Robert E. Lee Elementary School, which opened in 1951 and is the oldest school in use in Springdale.

Jim Rollins, the superintendent at the time, told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that the issue deserved attention. Three years later, the name is unchanged.

Jared Cleveland, who became Springdale's superintendent in July, said in an email that he had received a few emails and had talked to a few people who expressed concern about the school's name.

"Most have understood that the district focus has been on creating appropriate and essential plans for opening schools safely during a global pandemic," Cleveland said in September.

Cleveland said the School Board has discussed the district's facility plans for Lee Elementary. The board is considering repurposing the facility, he said, and if that decision becomes final, a new title may be used.

Repurposing of Lee Elementary could come as early as July 1, he said.

NO EASY SOLUTION

Historians and others said the review process is complicated because even though some historical figures committed questionable acts, their lives also included accomplishments worthy of recognition.

"What gets lost sometimes is the complexity of these issues," Woodruff said. "Not everything can be hammered down as white supremacy, but it's an underlying theme in most of these."

Willy Foote, Fulbright's grandson, said in a statement to the Democrat-Gazette that his grandfather's political actions on race should inspire a dialogue.

"While fundamentally a progressive man, his signature on the Southern Manifesto was the Faustian pact he made in order to stay in office in Arkansas," Foote said.

Despite his grandfather's positive impact, Foote said, Fulbright's political actions on race cast shame on his legacy and is something that should be discussed in situations such as Fayetteville's.

A 21-person committee formed by UA to evaluate Fulbright's presence on campus began meeting in late August and will continue to meet throughout the fall, Todd Shields, dean of UA's Fulbright College, said in an email.

Shields' email said the committee will explore Fulbright's "controversial and complex" legacy to determine whether the college that bears his name should be renamed and whether a statue that bears his likeness should remain. The university is consulting with Fulbright biographers, historians and scholars who study race, art displayed in public places, and other related topics.

The email said the committee also will consider renaming Charles Hillman Brough Commons.

Brough, a former Arkansas governor, taught at UA, according to the "Encyclopedia of Arkansas," which also notes that some historians rate him "as among the state's best governors."

But Brough also had a role in the Elaine Massacre of 1919, when many Black sharecroppers were killed after organizing a union, according to the "Encyclopedia of Arkansas." Brough relied on white informants and appointed a commission that was not asked to investigate the deaths but was instead tasked with "trying to prevent future such occurrences," according to the "Encyclopedia of Arkansas."

Shields said the committee will meet with Associated Student Government leaders and other student groups, executive committees for the faculty and staff senates, members of the alumni board and leaders from other campuses that are having similar discussions. He also said the general public will be able to weigh in through an online form.

The committee will make a recommendation to Chancellor Joe Steinmetz, but Shields said changes at the campus require approval from the University of Arkansas board of trustees.

McLarty, Harding University's president, said in his post that he chose to tell a more complete story of Benson's legacy that included "both the high points and the low points," but proponents for a name change say that response is inadequate.

"The auditorium is the central point on campus," Weiss said. "It is the very place where all students are required to gather every single day of the school week for chapel. To force Black students to enter a place named after someone who actively was against them being there is extremely hurtful and devastating."

A task force made up of students, faculty and board members, and alumni has been created to recognize Black achievement on campus. Chairman Greg Harris said the group has discussed several ways in which to honor Black heritage at the campus.

Harris, a Black man, said he doesn't view the Benson Auditorium decision as controversial and understands it was a difficult one.

"As a task force, we differ on the decision that was made this summer," he said. "We have not allowed that decision to keep us from our purpose of creating and affecting change at Harding University. If the matter of Benson should come up as a task to be addressed, we will be ready."

Woodruff, the Penn State University professor, said the nation must get rid of the "voluntary ignorance" it has adopted for many years.

"I think the younger generation for the most part wants to do this," she said. "It's time for older people to get out of the way. We need to listen to them and do everything we can to help them imagine a different world."

Janney said before 2017 she was in favor of keeping statues and names up while providing the proper context and using them as teaching tools, but her opinion has changed because meanings can change over time.

The naming of monuments and buildings was a product of the political culture of that time, she said, just as today's discussions reflect the current political climate.

"We need to be questioning every time we name something after someone," Janney said, "because it won't be viewed the same 100 years from now."