NEW YORK -- Adam Glenn pulled the tap handle, poured a Bud Light and passed the glass to a patron at Jimmy's Corner, his family's dive bar just off Times Square.

He kept an eye on the front door as customers returned for the first time in 18 months, and Etta James's "At Last" played on the jukebox. The house rule -- Let's Not Discuss Politics Here -- remained posted behind the bar, and new regulations were enforced.

"Can I see your I.D. and vaccination card?" he asked.

Sam Gong, a newcomer, furnished both. Glenn examined them.

"Just pull down your mask a little," Glenn said.

Gong complied.

"What can I get you?" Glenn asked.

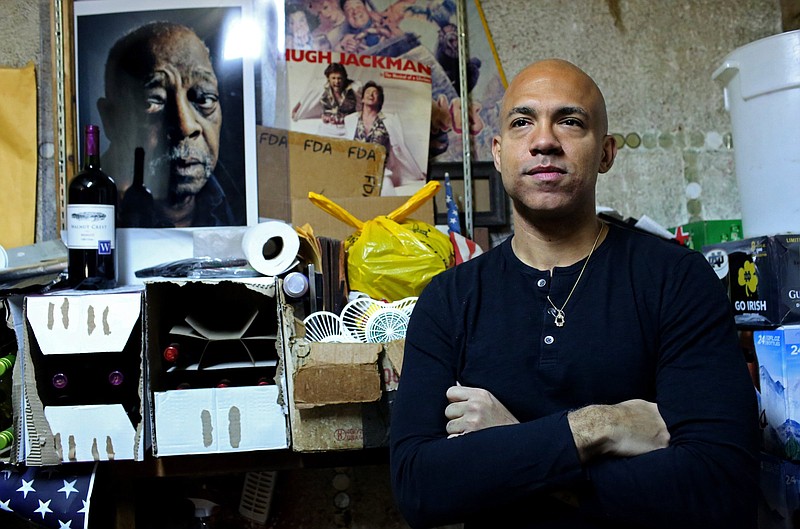

Glenn, 40, lost his father, Jimmy Glenn -- a boxer, trainer and cut man -- to covid-19 in May 2020. He was 89, and had still gone to his place at 10 o'clock each night with a pistol-grip cane and brown Stetson. Tattered electrical tape held together the brass rail, and Jimmy had left behind his old equipment -- suture scissors, adrenaline and Vaseline -- in a briefcase.

To reopen, Adam Glenn stitched together family savings and government relief. In defiance of inflation, beers still cost $3, cash only.

"We were ready for a rainy day," he said. "You just never think it is going to rain that long."

Jimmy knew a watering hole's worth. He grew up the grandson of a sharecropper in South Carolina before migrating to D.C., and then Harlem at 14. He dropped out of junior high school to support his mother, but soon happened upon a gym on 116th Street, where Ray Robinson trained. Jimmy studied the welterweight and fought Floyd Patterson before pivoting to life as a trainer. At 25, he became a father, and raised six children with his wife, Wynola, before they divorced.

He taught kids to box on the fifth floor of Third Moravian Church in Harlem, and developed a reputation for building character. Around that time, he met Swietlana Garbarska, a Jewish emigre from Poland who went by Swannie. He first saw her at Club 140, the site of what now is Jimmy's Corner.

He was 40 and a customer; she was 24 and a bartender. She hailed from Dzierzoniow and held a degree in Russian literature from the University of Warsaw. In December 1967, she flew to New York, where she planned to explore and work for six months. But when she wrote home in 1968, her parents told her to stay. Anti-semitism was spreading; they were leaving for Israel.

Together, Jimmy and Swannie -- who would become life partners -- opened Jimmy's Corner on the ground floor of a three-story brick building in the middle of 44th Street when the mafia and derelicts reigned in Times Square.

The bar, with its long, narrow corridor, attracted an eclectic cast that included Broadway stagehands as well as Finnish film director Aki Kaurismaki. Jimmy ran his place like a reliquary, filling his hole in the wall with framed photographs of fellow pugilists and pasting snapshots of patrons on the bartop. He nailed a ringside bell from Madison Square Garden to the stucco wall, and if anyone rang it, he had to buy the bar a round. In 1979, a producer working on Martin Scorsese's "Raging Bull" stopped in. Soon after, Jimmy Glenn Jr. showed up to work after school to find the bar transformed into a movie set.

"The craziest, coolest, most absurd parade," Tom Berman, a regular, said recently.

Adam Glenn, Jimmy and Swannie's only child, was born in 1981. He spoke Polish before English, and first climbed on a chair to fill a bucket with ice at the bar when he was 3. At 7, he took cash deposits from the bar to the bank. By the time he was a teenager, he stayed at the bar past midnight before going home with his mother. They waited for Jimmy to return after closing.

"Our family time was at 4 a.m.," he said.

Adam Glenn excelled in school, graduating from Stuyvesant High -- the city's flagship public school -- and Wesleyan University in Connecticut before returning to New York in 2003. He honed his oratorical skills in barroom debates before enrolling at Harvard Law School. He then worked at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, a law firm four blocks from Jimmy's, where he was a self-described "monster," billing 2,500 hours per year. Still, he moonlighted as a bartender. One weekend, his parents went away, so he worked in the back, poking his head out to monitor customers as he closed a deal.

In May 2014, Swannie -- who had smoked for 50 years -- received diagnoses of rectal and lung cancer. She worked through chemotherapy, but poured her last beer that fall. To help his father, Adam placed orders and kept the books. In January 2015, Swannie died. Soon after, Adam left the law to manage fighters, as well as the bar.

"The law wasn't going to fulfill me forever," he said.

A few years ago, the building next to Jimmy's Corner was slated to be demolished by the Durst Organization, and considerations were made to level Jimmy's, too. Douglas Durst, the chairman, used to drop off his children at the bar for Jimmy to baby sit them while they played pinball. Jimmy also once saw two men following Durst's father, Seymour, and shadowed them for 18 blocks until Seymour got home. Durst remembered that and spared Jimmy's Corner.

"We couldn't do that to Jimmy," said Durst, who tore down the building next door and then put up steel beams in the vacant lot to physically support Jimmy's Corner.

On March 14, 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic started ravaging in New York, Jimmy visited the bar at 2 a.m. after staying away a few nights. Two days later, the city ordered the establishment closed, and Adam stayed with Jimmy. Then, in early April, Adam, his girlfriend and Jimmy stopped by the bar to put new CDs in the jukebox.

But by the time they left, Jimmy looked worn. A few days later, Adam took him to NYU Langone's emergency room, and he argued his way in so he could visit his father. Jimmy died a month later.

"He just seemed indestructible," Durst said. "It was hard to imagine he was no longer with us."

Adam vowed to reopen the bar, and received aid from the Small Business Administration's Paycheck Protection Program. He reviewed his father's business, which had been healthy.

One day, Jimmy's grandson Donta uploaded a playlist of the jukebox's greatest hits on Spotify so regulars could feel like they were at the bar. When they officially reopened last month, Adam and Jimmy Jr. displayed one of their father's hats and canes in a memorial, but within weeks, someone stole them.

On a recent Saturday, "Crimson and Clover" played as theater-goers carried in playbills, opened tabs and paid respects. Business was picking up even as the Partnership for New York City, a nonprofit organization composed of business leaders, reported that only 28% of Manhattan office workers were back on weekdays. International travelers were scheduled to arrive soon to give tourism a boost, and Adam answered the pay phone on the wall -- the only landline -- to confirm that the bar was open.

"I don't have any illusions that a three-story building is going to survive in Times Square another 100 years," he said, "but as long as it's here -- and hopefully it is another 20 to 30 years -- we want to be right here."

Around 2 a.m., he departed, and Jimmy Jr. heard glass shatter up front. A drunk man bumped into a framed photograph of Muhammad Ali affixing his right fist to Jimmy's chin at Jimmy's old gym. The offender offered to pay $5 for it.

"You need to leave," Jimmy Jr. said.

He took the broken glass to the back office, where a few of his father's corner jackets still hung on a rack. He looked out on the last few revelers and recited Jimmy's lullaby, the one he sang to patrons at last call.

"Baby, don't you want to go home?" he said. "Why you still sitting in my bar? Isn't there a man or woman? Don't matter as long as you got love waiting for you."