So many things come to mind when we think of Johnny Cash. There is the distinctive sound of his early Sun Records hits; the somber image he cultivated as the Man in Black; his devotion to Christianity and his struggle with drugs; his compassion for those forgotten by society; and the songs — "Ring of Fire" "Folsom Prison Blues," "Five Feet High and Rising," "Sunday Morning Coming Down," "I Walk the Line," "Hurt," "I've Been Everywhere" just to name a few.

Then there's Arkansas, Cash's first home. He was born in Kingsland, grew up in Dyess and though he left Arkansas for the Air Force and then to live in Memphis, California and Tennessee, he returned here often, to the place that helped mold him into the complex, contradictory man, artist and public figure he became.

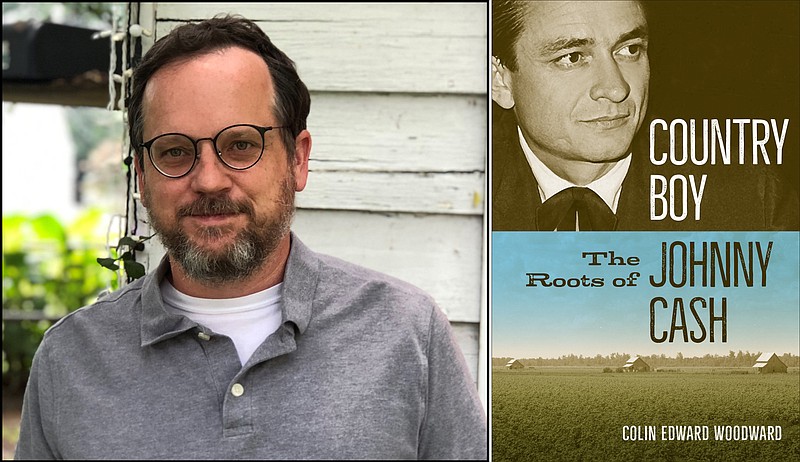

A new book, "Country Boy: The Roots of Johnny Cash" by Colin Edward Woodward, delves into the undeniable influence Arkansas had on the art, career and life of the Man in Black.

"No one has ever sounded quite like Johnny Cash. But there's no place quite like Arkansas either," Woodward writes.

■ ■ ■

Published July 29 by the University of Arkansas Press, the 351-page book is not a comprehensive exploration of Cash's life and influence. For that, Woodward helpfully recommends Robert Hilburn's "Johnny Cash: The Life."

Woodward, the author of "Marching Masters: Slavery, Race, and the Confederate Army" and the host of the "American Rambler," a podcast about history and pop culture, skillfully balances his writing with the authority of a scholar and the enthusiasm of a discerning fan. A native of Worcester County, Mass., Woodward has a doctorate in history from Louisiana State University. He moved to Little Rock in 2012 and spent three years as an archivist for the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Now living in Richmond, Va., Woodward, 46, says he became interested in Cash during graduate school after hearing the three-CD boxed set "The Essential Johnny Cash: 1955-1983."

"I still listen to that a lot," he says. "But I didn't listen to him growing up. No one that I knew listened to country music where I'm from. It was being in the South that I picked up my love of Cash."

Work on the Cash book started while Woodward was living in Little Rock.

"It just kept snowballing and I thought I could expand it into a book using Arkansas as the central component," he says. "[The state] is so central to his story, and you can tell all these other stories based on what's happening to him in Arkansas."

Cash returned for concerts and public appearances, of course, but also for more low-key homecomings.

"Family was a big part of him coming back, but like he said during the 1994 concert [in Kingsland], he would come back 'to touch my roots again.' He liked being grounded and Arkansas grounded him. He liked the people of the state. For a guy that was on the road so much, I think Arkansas was home to him in a way that Tennessee wasn't."

Woodward hits the Cash highlights (and not-so-highlights) — how he started making music in the Air Force, his string of hits with the Tennessee Two (guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist Marshall Grant), fame, his troubled first marriage to Vivian Liberto Cash, new albums, his activism for prisoners and American Indians, his love affair with folk and gospel, his marriage to June Carter Cash, addiction, periods of sobriety, fading fame, comebacks, etc.

He also digs into Cash's ancestry, which dates to the 1600s in Scotland and the story of Dyess, the community founded in 1934 as Dyess Colony and that was part of the Roosevelt Administration's resettlement program for impoverished farmers (first lady Eleanor Roosevelt actually visited Dyess in 1936).

■ ■ ■

Cash, who died Sept. 12, 2003, at 71, could be mercurial. Woodward pinpoints the singer's personality and appeal in a passage about "Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian," the singer's 1964 concept album (for most of his life, Cash was falsely under the impression that he had Cherokee ancestors).

Though the album contained the hit "The Ballad of Ira Hayes," Cash was perturbed by the lack of attention the record received from country radio and wrote an angry, rambling letter to Billboard that was published in August 1964.

Woodward writes: "The letter was classic Cash: honest, misguided, melodramatic, desperate, angry — and above all, passionate about his music."

This was during one of many tumultuous times in Cash's life. His first marriage was in trouble and his addiction to pills was going strong.

"The letter is a little crazy and incoherent at times," Woodward says. "But even when he's sort of off the rails, he's still defending his music. That's an interesting time for him. His personal life is getting wrecked, but the music is still really good and ambitious."

Woodward notes that an album like "Bitter Tears," and Cash's love of Bob Dylan, are evidence of his sometimes hard to categorize artistry.

"I wanted to talk about the music in between the Sun stuff and [1968's comeback album 'Johnny Cash: At Folsom Prison']. There's a lot there. He's trying to change his identity; Dylan has come on and Cash is getting into the folk scene. It's a really interesting period."

■ ■ ■

The book comes at a time when Cash has been in the news around these parts.

The singer is featured in "1968: A Folsom Redemption," a photo exhibit at The Center for Humanities and Arts at University of Arkansas Pulaski Tech in North Little Rock that focuses on Cash's concert at Folsom State Prison in California.

There's the statue of Cash sculpted by Little Rock artist Kevin Kresse that, along with a statue of Daisy Bates, will soon represent Arkansas at the U.S. Capitol. More lightheartedly, there was the incident in May when a sharpshooting vandal fired a strategically placed bullet through a silhouette of Cash on a water tower in Cash's birthplace of Kingsland that resulted in a bevy of headlines and stories with references to "springing a leak."

Woodward says he wrote the book "to reclaim Cash for Arkansas. That's where he was born, where he grew up. I wanted to tell those stories about Arkansas."

There are a couple of small mistakes in the text. Woodward misspells the first name of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, and mistakenly writes that Elvis Presley didn't perform in Arkansas after the 1950s.

The book aptly ends in Dyess. The Johnny Cash Boyhood Home, which was bought by Arkansas State University in 2011 and restored through proceeds from the annual Johnny Cash Heritage Festival, has become an attraction in Dyess.

"I wanted it [to] kind of go full circle, starting with him in Kingsland and Dyess and ending with the restoration in Dyess," Woodward says. "The restoration is really important. I don't know if I would have written the book the same way if they hadn't done that restoration. It was a great conclusion to the story. This is where he grew up and, in a lot of ways, this is his legacy."