Greg Loyd is gregarious, seems to always be smiling and loves to talk.

Sitting recently with a group at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences speech and language clinic in Little Rock, Loyd, a former chef from Little Rock, entertained with an animated story about growing vegetables in his back yard.

"I grow them from seeds, the...," Loyd trailed off, he closed his eyes momentarily, searching for that last word.

The word is there in his mind's eye.

Tomatoes.

He knows the life cycle of the plant and even the complicated scientific words to describe its botany.

But the simple word, "tomatoes," is lost somewhere between his mind and his voice.

"Aphasia," he says, matter-of-factly.

In 2012, Loyd was undergoing kidney dialysis at his home. He stood up for a moment only to fall and hit his head. The next thing he remembers is waking up in a hospital.

Today, the aphasia is the only sign of a stroke that left him hospitalized for months and enduring rehabilitation for years.

Aphasia is a language impairment, affecting a person's ability to communicate, whether through speech or the ability to read, write or understand spoken or written language.

It is always caused by a brain injury that can occur after such things as a stroke, head injury, brain tumor or a degenerative disease such as Alzheimer's.

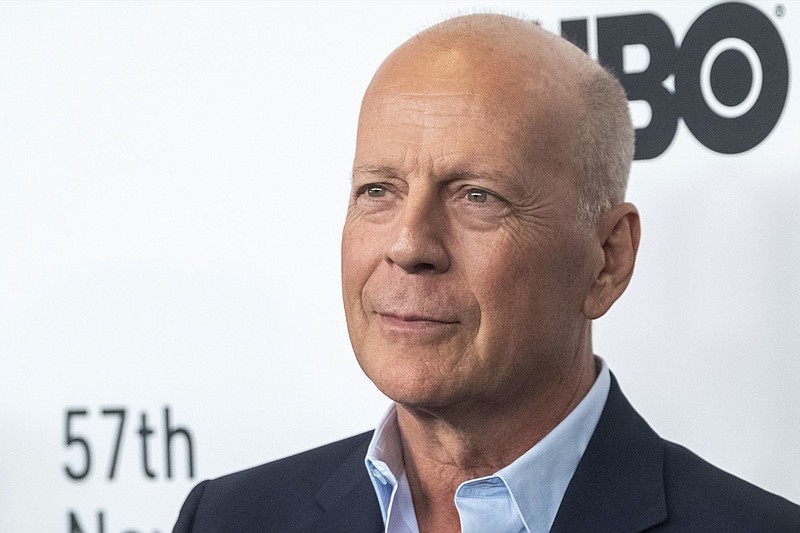

Aphasia was mostly unknown outside the clinical world -- even though more than 2 million Americans are afflicted with it -- until it was announced recently that Hollywood actor Bruce Willis was diagnosed with the condition.

Those who worked with Willis -- who retired from his acting career after the diagnosis -- had grown concerned about his decline, according to news reports. The actor struggled to remember his dialogue and required accommodations like an earpiece to feed him his lines and shortened lines.

Like Willis, Loyd had to give up his career as a chef in upscale Little Rock restaurants.

LIVING WITH APHASIA

Loyd knows he's lucky.

Not that the road hasn't been difficult or that he hasn't experienced the irritability and frustration that comes with the condition, but he's optimistic by nature. He sought out therapies, diving into programs and seeking the company of others afflicted with aphasia.

It didn't take him long to connect with the UAMS speech and language clinic. The center's services are provided by graduate students under the direct supervision of licensed faculty who are also certified by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

"Really, once I came into this class, I felt like I was at home. I felt so normal coming into these classes," Loyd said. "We'll work on reading classes. We can all read, but when it comes to reading out loud, we're a little slower at it. And our eyesights are all different, so we all look at it differently. But we always do a team reading. One of us will read a section and someone else will read a section."

The clinic serves patients of all ages, from infants to adults. The services, when it comes to aphasia, begin with diagnostic services and continue through individual and group speech, language and literacy therapy sessions.

"We have several different groups and what we offer each semester may be different," Dana Moser, associate professor and director of the UAMS speech-language pathology program, said.

The group includes adults who have aphasia, motor speech disorders or other speech and language problems caused by brain injury or neuromuscular diseases.

The group also teaches patients other modes of communication.

In one group activity, the patients were given a week to take random photos of their lives then talk in class about the different aspects of living with aphasia.

"In all the years that I've been working with people with aphasia, I have seen so much resiliency. When we did the photo voice assignment, a lot of the stuff that we talked about in that group were the challenges you face and what it's like to live with aphasia," Moser said. "The story that they told was that there was loss and then there was adaptation and then there was reinvention of themselves. It's like they found new ways to be engaged, to find meaning and purpose in life from their old life."

It was in this assignment that Loyd introduced his friends and clinicians to his new love of gardening.

Mostly, Lloyd said, the group class shows people like him that they aren't alone.

Concern crosses his face as Loyd worries aloud about a friend who has stopped attending.

"I've called and emailed," Loyd said.

Portia Carr, assistant professor of UAMS speech-language pathology, said groups focus on verbal expression, auditory comprehension, reading and writing.

"We try to make all the tasks conversational and very comfortable to help to improve their quality of life and their ability to participate in everyday life activities," Carr said.

Loyd said the group gives him the confidence to keep talking.

"I'm empowered," Loyd said. "I wish I could move up in my recovery more. I'm not where I want to be, but this clinic has gotten me to where I am."

UNDERSTANDING APHASIA

Aphasia can range from so severe that patients are unable to communicate at all to being so mild that it is undetectable to others.

It's different for each patient. Sufferers can lose the ability to retrieve the names of objects or the ability to read, while others cannot put words together into sentences. It's common that multiple aspects of communication are impaired at the same time.

"Aphasia can affect your ability to just use language in general. That could be expressing it or understanding what someone is saying to you. It could be understanding what you're reading and it could also be being able to write something out," Moser said. "Depending on which part of the person's brain is damaged, it looks different for different people."

Loyd can fly under the radar most of the time, Moser said.

"It's hard for me because I want to say a smart, fancy word, but I can't do that," Loyd said. "I have to say the most short and simple thing that I can that relates to whatever the conversation is."

Loyd said a fellow group member couldn't speak because of aphasia, but he could type out whatever he wanted.

Physical aphasia symptoms can also be present. People with aphasia can also have right-sided weakness or paralysis of the leg and arm because the left side of the brain is the side generally damaged.

There are several types of aphasia, including global, mixed transcortical, Broca's, transcortical motor, Wernicke's, transcortical sensory, conduction and anomic.

An aphasia patient doesn't typically fit solely in one type of the condition and other types of aphasia exist beyond the predominant eight.

Moser said the lack of language expression skills often makes outsiders believe the aphasia patient has lost cognitive ability, but their intelligence remains the same. It's the ability to communicate that is lost. Likewise, the memories of an aphasia patient remain intact, but the ability to access ideas and thoughts via language is disrupted.

While the onset of aphasia is sudden, the individual can progressively improve over time.

According to the National Aphasia Association, about half of those who initially show aphasia symptoms recover completely within the first few hours or days. If aphasia symptoms remain beyond the first few months after a stroke, complete recovery is unlikely, but improvements and accommodation skills can be achieved even over a period of years or decades.

GROWING A FUTURE

On a recent hot day, Loyd was in his garden. Sweat rolled down his face and visitors were greeted with a wide grin.

Raised beds bordered with wooden planks took up the once large and open yard.

Arkansas Traveler tomato plants sprung from the ground, encased by wire cages.

Loyd spoke clearly and the word "tomatoes" rolled easily and quickly off his tongue.

He pointed to the green sprigs of red potatoes coming up in pots. He's growing the red ones, he said, but it's the Kennebec potatoes that make the best French fries.

"They're crisp on the outside and soft in the middle," he said.

Loyd's family and friends aren't phased, he said, when he can't get a word out during a conversation. They laugh together and help him retrieve the word.

He carries an aphasia identification card with him when he's in public in case he struggles to communicate. The card explains aphasia and asks for patience.

"At the beginning, I would get mad and frustrated," he said. "But the clinic has made it normal to me now."

He has a life with purpose, he said. He wants to bring more awareness of the condition by continuing to share his story and he wants others, newly diagnosed, to know that they have a future.

"This can happen to anyone, but there's hope," he said. "For me, it was gardening, starting from seed. As soon as I open up the back door and I see the gardens, it just feels so great."

He moved from one plant bed to the next.

"Zucchini."

"Banana peppers."

"Collard greens."

The words flowed off his tongue.